The arrival and setting up base by the Portuguese in India in the sixteenth century heralded several consequences, some of which are well-known and easily identifiable like the introduction of fruits and animals. Since the Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive in the Indian sub-continent, they kind of became a point of contact between India and Europe, not only introducing the other European countries to Indian produce and products but also leading to their demand in foreign markets. The scarcity of documented sources makes it difficult to assess the actual impact of the Portuguese presence in the Indian sub-continent, but as is widely known, the pineapple fruit, a native produce of South America, the dodo, a flightless bird, the turkey and the exotic monkey were introduced by Portuguese merchants and traders during their commercial tenure in India. Such points of contact between the two countries opened up newer vistas in socio-cultural relations in the coming years.

Not being restricted to importing items of flora and fauna alone, it was the introduction of tobacco from America by the Portuguese that engrossed the Indian emperors’ lives of leisure and social activity. The spirit of enterprise of the Portuguese merchants and traders was a significant factor that linked Europe to India, America, Africa and other regions of Asia thereby laying the foundations for trade on a worldwide scale.

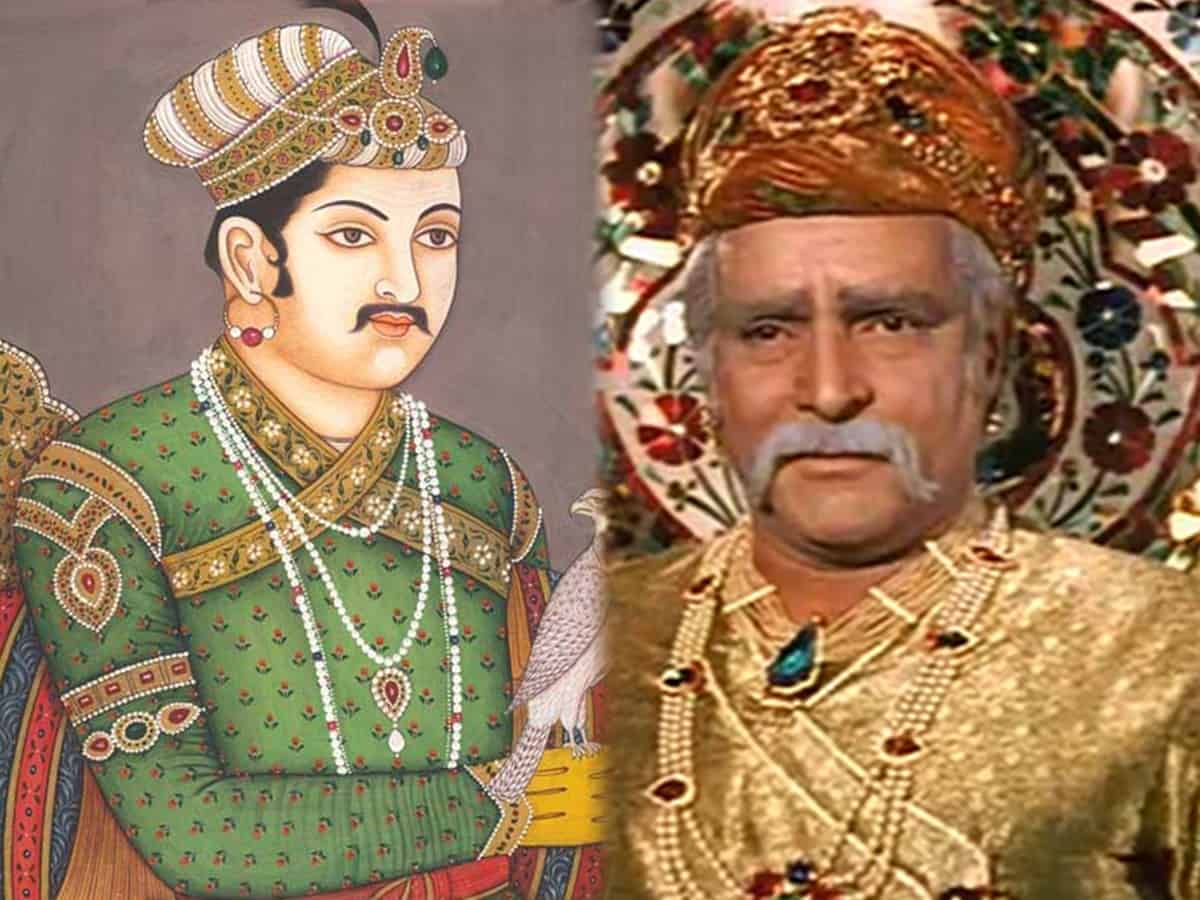

The tobacco plant was introduced into Portugal in 1558. Although the precise date when the tobacco plant reached the Indian sub-continent is not known, the Mughal court chroniclers provide the date of the appearance of tobacco as 1604 when Akbar became the first Mughal emperor to inhale tobacco smoke having received it as a gift from one of his favourite courtiers, Asad Beg, who in turn had experienced it earlier at the royal court of the sultanate of Bijapur.

The political and geographical specificities of medieval Deccan show that as a result of trade and manufacture of exquisite cultural products in the Deccani courts, many new elite practices came up. Given the proximity of the Adil Shahi sultanate to the Western Coast of peninsular India where the Portuguese were located, it seems valid to conclude that the growing of tobacco first expanded in the Bijapur sultanate region of the Deccan. Asad Beg, a Mughal envoy to the court of Ibrahim Adil Shah, mentions that the tobacco plant was hitherto unknown to him. When Asad Beg was sent to Bijapur in the late sixteenth century by his master, Shaikh Abul Fazl, a favourite courtier of emperor Akbar, in pursuit of another Mughal envoy Mir Jamaluddin Hussain Inju Shirazi, he got acquainted with the product and its use. Muzaffar Alam and Sanjay Subrahmanyam give a lengthy, interesting account of Asad Beg’s narrative Waqai i Asad Beg down to the finest of details.

Asad Beg, who was on an important assignment to the Bijapur court, after many efforts was welcomed by Ibrahim Adil Shah with due pomp and ceremony as would befit a Mughal envoy. High quality food and drink, festivities, slaves, Arab horses, elephants, weaponry, silver and golden trays with special chintz from the looms of Karnatak, fresh fruits, good fodder formed the material wares presented to him. The Mughal envoy from his master’s side carried with him equally elaborate presents in the form of horses, camels, Kashmiri shawls, expensive European cloth known as parchaha i nafis i wilayat. After all, Asad Beg was pursuing the task deputed to the earlier Mughal envoy of arranging the marriage of Ibrahim Adil Shah’s daughter and the Mughal prince, Daniyal. In the meanwhile, as he was waiting to meet Ibrahim Adil Shah this material exchange of luxury presents was done. Asad Beg not only had to take back Jamaluddin Hussain Inju Shirazi to Agra but also had to carry back expensive goods and wealth (zar-o-mal) from the Deccan as tribute for his master. Asad Beg was initiated into inhaling tobacco while on this assignment at Bijapur. To consume it, he was given a jewelled pipe through which he inhaled the smoke. As part of the lavish exchange, Asad Beg carried back expensive tobacco to Agra which the emperor used until he was stopped by his doctor who forbade him to smoke. Even then, tobacco gave rise to contradictory reactions. Many Europeans believed it had beneficial pharmacological reactions, while many even rejected it because it was something new.

Mughal emperor Jahangir, unlike his father, might have been the first ruler to forbid tobacco. Although the emperor was a connoisseur of narcotics and alcohol based drinks, he prohibited the use of tobacco in 1617. This was an unsuccessful attempt as people who had got used to its consumption were not interested in obeying any anti smoking edicts issued by the ruling dispensation. The large number of huqqas or water pipes used for smoking made of precious and semi precious metals and stones found a vast audience both among the elites of Mughal India and in the Deccan.

As Emma Flatt says, ‘………Indian courtiers from other Indian courts also spoke admiringly of the Deccan and its riches, which seemed to have been at the forefront of new trends in the consumption of exotic goods, as the Mughal envoy Asad Beg Qazvini, despatched as Akbar’s envoy to Bijapur in the early 1590s, discovered’:

“In Bijapur I had found some tobacco. Never having seen the like in India, I brought some with me, and prepared a handsome pipe of jewel work. The stem, the finest to be procured at Achen, was three cubits in length, beautifully dried and coloured at both ends being adorned with jewels and enamel. I happened to come across a very handsome mouthpiece of Yaman cornelian, oval-shaped which I set to the stem; the whole was very handsome. There was also a golden burner for lighting it, as a proper accompaniment. Adil Khan [the Sultan of Bijapur] had given me a betel bag, of very superior workmanship; this I filled with fine tobacco … I arranged all elegantly on a silver tray. I had a silver tube made to keep the stem in and that too was covered with purple velvet.”

‘In Asad Beg’s account, not only does he discover a new and exotic drug, unfamiliar to members of the Mughal court, in the bazaars of Bijapur, but also manages to obtain highly ornate and bejewelled exemplars of all the correct material accessories for consuming that drug.’

Asad Beg’s narrative implies that the royalty and nobility of Bijapur were already familiar with the consumption of tobacco and had adopted it as an elite practice, while the nobles in the Mughal court and emperor Akbar were still ignorant of it. This also showcases the fact that the Deccan had emerged as one of the leading markets for rare and exotic items in those times. Tobacco thus became a heavily traded commodity creating a demand at the imperial and provincial courts of the Indian sub-continent, even in later periods. It also became a much desired gift to be given and received from emissaries visiting royal courts to establish diplomatic contacts. This in turn also brought together the European and Indian cultures.

Salma Ahmed Farooqui is Professor at H.K.Sherwani Centre for Deccan Studies, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad. She is also India Office In-charge of Association for the Study of Persianate Societies (ASPS).