This day, 36 years ago, Aryabhatta, the rudimentary satellite, built indigenously by Indian space scientists and weighing 360 kg, successfully zoomed into space. It launched the country’s spectacular journey of conquests in space technology that are often described as based on ‘frugal innovations, low budget but huge societal benefit’.

In 2017, the nation’s launched capabilities peaked with a world record of placing 104 satellites through its Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV). The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has probes circling the Moon and Mars, sending pictures already. It was aiming to send humans through the Gaganyaan project.

After a lull due to the Pandemic in 2020, the ISRO has stepped on the accelerator with a slew of projects, including the probe to the Sun, under project Aditya-L1, Chandrayaan -3, Mars Orbiter-2 and a dozen launches.

Aryabhatta saga

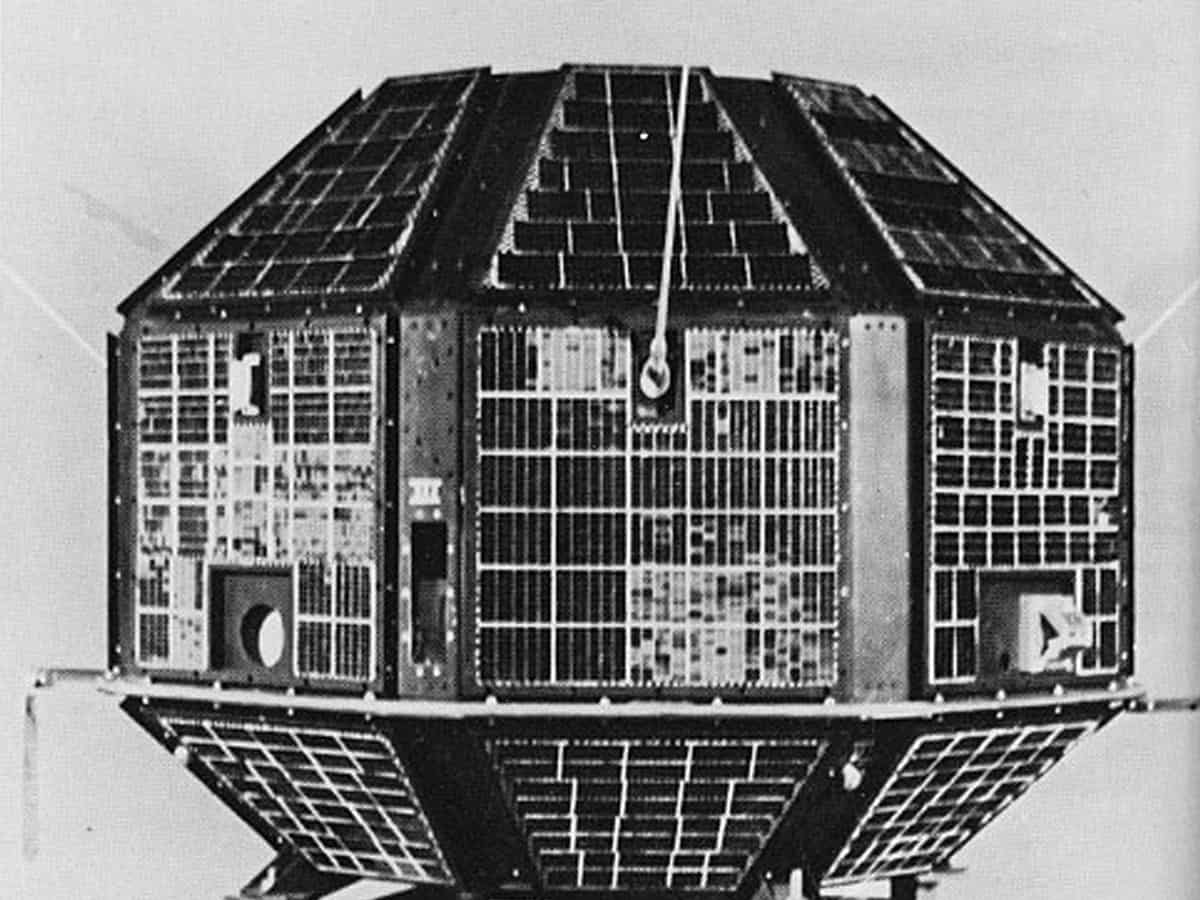

The spacecraft, named after the Astronomer, Aryabhatta was India’s first experimental satellite. It was launched by the Soviet Kosmos-3M rocket from Kapustin Yar, Volvograd Launch Station in present day Russia on April 19, 1975.

Aryabhatta carried a payload to study X-ray astronomy, aeronomy and solar physics. It’s mission life and orbital life lasted 17 years as it reentered the earth orbit on February 10, 1992, according to the ISRO.

Prof U R Rao, the NASA trained scientist led the team that built the satellite in ISRO under the chairmanship of Prof Satish Dhawan (1972-82).

Interestingly, on March 10, 2021 Google Inc. celebrated the 89th birth anniversary of Prof Rao with its typical Doodle stating that it was honouring India’s Satellite Man.

The Aryabhatta story reflects the true non-aligned nature of India’s international relations too in a way. In the 1970s, India embarked on its own satellite programme. Dr Vikram Sarabhai, the visionary, first Chairman of ISRO formed a group of researchers and engineers led by Prof U R Rao for the purpose.

The sudden death of Sarabhai in December 1971 was a setback. However, the Prime Minister, Mrs Indira Gandhi at her peak after the victory over Pakistan and liberation of Bangladesh fully backed the programme.

Prof Satish Dhawan, who took over the reins of ISRO in 1972, stood ‘ rock solid’ behind the development team. The U R Rao team took less than 3 years to build the satellite at an estimated cost of Rs 3 crore and was ready by 1975.

Hyderabad connection

During the development phase, a satellite model, roughly half in size of the final version was tested out on a balloon flown at about 25 km altitude from Hyderabad on May 25, 1973, according to the Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre, Thiruvananthapuram.

The Balloon Facility of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research is located in the city and has done pioneering experiments using atmospheric balloons over the last 50 years.

After scouting for launch vehicles in the US, France and Soviet Union, an agreement was signed with the Russians. The nation’s mood soared after the triumphant launch from Russia in 1975.

The historic event was celebrated by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which issued a special Rs 2 currency note with the picture of the satellite from 1976. Interestingly, the Soviet Union, which supported India’s space programme too issued a special stamp in 1984 with the Aryabhatta and Bhaskara satellites.

But, Aryabhatta was not a big success in real space terms. It’s onboard systems failed and the Satellite tracking centre of ISRO in Bengaluru lost contact within weeks. It, however, laid the foundations of technology to build satellites and take on launch vehicle technology in the ISRO.

Aryabhatta spurs ISRO projects

Riding in the positives of the Aryabhatta launch the ISRO took up the Satellite Launch Vehicle (SLV) project to begin placing payloads of about 40 kg into the Low Earth Orbit from Sriharikota, the country’s launch pad.

The first attempt of the experimental SLV3 in August 1979 was a disaster. However, the next test flight in July 1980, the ISRO came out triumphant. Here too, it was the leadership of Prof Satish Dhawan that won the day for Indian space.

In the word’s of former President, APJ Abdul Kalam, who was the Project leader of SLV3, “When the first experimental flight failed in August 1979 and the entire team was glum faced, Prof Dhawan as Chairman, ISRO, owned up the failure and explained the situation”.

A year later, when the flight succeeded, the same Prof Dhawan, asked Mr Kalam and team to explain the success to the media, while he took the back seat. A huge lesson in great leadership was what the former President would often cite in his lectures to students across the country.

Thereafter, from 1982-92, under the Chairmanship of Prof UR Rao, the ISRO went on to build the PSLV, the ASLV (Augmented Satellite Launch Vehicle) and entered the GSLV (Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle) development phase.

Ironically, the scientist, who made fundamental contributions to the indigenous cryogenic rocket technology, Dr Nambi Narayanan, got framed in the infamous ‘ ISRO Spy Case’, from which he was absolved recently, meagre compensations announced and a film made on his life. But the fact remains that that unsavoury episode put back the GSLV programme by over a decade.

Today, the ISRO has opened up to private participation in satellite building and other key projects too. It has embarked on Chandrayaan -3, Mars project and other interplanetary voyages in future.

Simultaneously, start ups are entering and private companies taking up challenging projects to spur India’s space odyssey to greater heights.

Somasekhar Mulugu, former Associate Editor & Chief of Bureau of The Hindu BusinessLine, is a well-known political, business and science writer and analyst based in Hyderabad