It is past midnight on Shab-e-Baraat. Unlike previous years on this pious occasion, I don’t see fireworks or hear firecrackers. And my wife has not prepared halwa, a sweet dish special for this occasion. The eerie silence on the roads and the absence of footfalls in the mohallas are so uncharacteristic of Shab-e-Baraat. Mosques are shut. So are graveyards, mausoleums and mazaars (Sufi shrines). Those praying are praying at home.

We are under lockdown. Restrictions have undeniably brought disruptions. I have full sympathy for the millions who have been reduced to worry about their next meal. But here I am trying to see the brighter side of the forced “house arrest.”

Is it not a mercy that we are alive today? Is it not a mercy that you are reading what I wrote just hours ago? The rising number of coronavirus positives and deaths caused by this pandemic has brought us together. Rich or poor, highly qualified or utterly uneducated, gainfully employed or hopelessly jobless—nobody can claim he is beyond the reach of the apocalyptic coronavirus. Few in the world are as protected and empowered as Prime Minister of England Boris Johnson. He too was humbled and had to be put in ICU as the virus infected him. Mercifully, he is out of ICU but still in hospital.

In the last two weeks or so we have seen and heard total strangers reaching out to people in distress. There are organisations and individuals, many of doubtful credentials when it comes to spreading communal harmony and upholding human rights, who are volunteering to relieve the pains of the stranded, stuck and hungry. There are doctors, nurses and paramedical staffs who are risking their own lives to save lives. Is it not a mercy that humanity is alive? Is it not a mercy that, despite our differences of religion and politics, of dietary habits and linguistic proficiencies, we stand together to fight this pandemic?

Has not this lockdown proved a blessing in disguise? In a long time, I got so much time to read books. I can read books also because half a dozen daily newspapers that I subscribed to have stopped reaching my reading table in the morning. So what do I do while I take the morning tea? I check messages on social media networks and then switch over to reading a book. I don’t get up until I have finished at least one chapter of a book in the morning. If you begin enjoying reading books, you will stop enjoying everything else in the world. Reading books is not just about encountering words, people and places. It is also about refuelling your minds, sharpening your thoughts and opening vistas for new possibilities.

Once upon a time, I was a big film buff. When I was at AMU, I got hooked on to Hindi films. There was a time when I would see at least two movies a week. Adjacent to AMU’s western boundary is Shamshad Market, then famous more for machchar (mosquitoes) in the night and makhi (flies) by the day. These two beautiful creatures hung and hummed around half a dozen chaikhanas which also kept biscuits and namakpaade (a crunchy snack).

Some of the male students whose heart was neither in studies nor had they got a better thing to do, say, for instance, loiter around the girls’ hostel in the guise of being female students’ cousins or brothers, spent hours at the chaikhanas.

I was neither interested in studies what I was forced to –that is another story for another day–nor had I a genuine or fake “sister” to meet. Apart from reading the unreadable at the varsity’s central library, I watched films. All sorts of films. Good, bad, ugly. A reason why some of us saw so many films was that the tickets were damn cheap. And the mode of transport from Shamshad Market to the cinema Halls in the city, across the kathpulla (wooden bridge), bicycled we hired by paying 50 paise per hour. The cycle owner was not a fool. He would keep our identity cards in surety lest anyone tried to scoot. I saw innumerable films through this convenience.

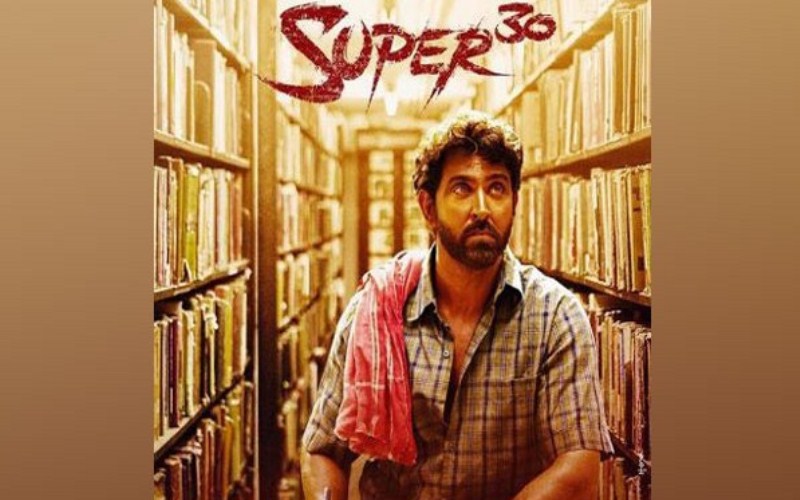

After a long time, in decades, I got chance to see films not when I am rushed. The other day Hrithik Roshan-starrer Super 30 was telecast on Television. The kids informed me when it came on screen. I sat glued to the TV not because it has steamy scenes or great songs and dance. I got captivated by its story, drama and the melodrama. Coming from almost the same background that the movie features major characters—a crazy, dedicated teacher Anand Sir (Hrithik Roshan) and his many impoverished pupils with dreams to reach NASA, Indian Science Centre, big positions with Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) as launch pads, I could easily relate to the story. One of the highpoints that made me cry and also inspired is when, after the principal of a rival coaching centre threatens Anand Sir and his students, the students are down with depression but soon get a pep talk which turns into a mantra to cross the barriers.

The biggest taunt that enormously haunts Hrithik Roshan aka Anand Sir is: Raja ka beta hi Raja banega (a king’s son alone can become king). Leaving his food that he is having with his brother at home untouched, Anand Sir rushes to the students’ ramshackle room and is pained to see his pupils infinitely worried about their future. “Tumhare paas khone ke liye kya hai (What do you have to lose)?,” Anand Sir asks his students rhetorically. These are first-generation learners, wards of taxi drivers, farm labourers and bus conductors. They had nothing to lose but the chains of privation, the humiliation of being poor. Anand Sir’s inspiring words make these IIT aspirants shed fear and embolden them to face the challenge.

The same question was at the back of my mind when I charted on an uncertain journey to a strange city, Mumbai, decades ago? What did I have that I was afraid of losing? Rs 800 that I had saved from my salary from a previous job in Delhi after buying the second class sleeper ticket by a train? Was it not small mercy that Rs 800 in my pocket was my own which I had earned, not borrowed or stolen?

Woh shabnam kā sukūñ ho yā ki parvāne kī betābī

(Whether it is stillness of the dew or desperation of the moth/If there is determination to fly, they will get the wings)

Agar udne kī dhun hogī to hoñge bāl-o-par paidā