Seldom could any Indian city vie with Bhagalpur as far as the use of multifarious adjectives is concerned. It is the city where the chopped off organ of Kamdev is believed to have been landed. Mahabharat describes it as the area where Angraj Karan ruled for many years.

For a long time, it has had several sobriquets to its credit. Once known as a silk city, a city of bedsheets and stoles, it later emerged as a city of crimes. In 1980 it became “Ganga Jal city” as the police used this term for pouring acid into the eyes of the undertrials. The frenzied communal violence engulfed the city in 1989, and the gruesome killings of more than one thousand people gave the city a new tag of a territory of “decimation”. Despite having attained notoriety for widening communal divide and fostering enmity, Bhagalpur is still a city where the life of desire and longing for close affinity beyond all sorts of barriers binds people together.

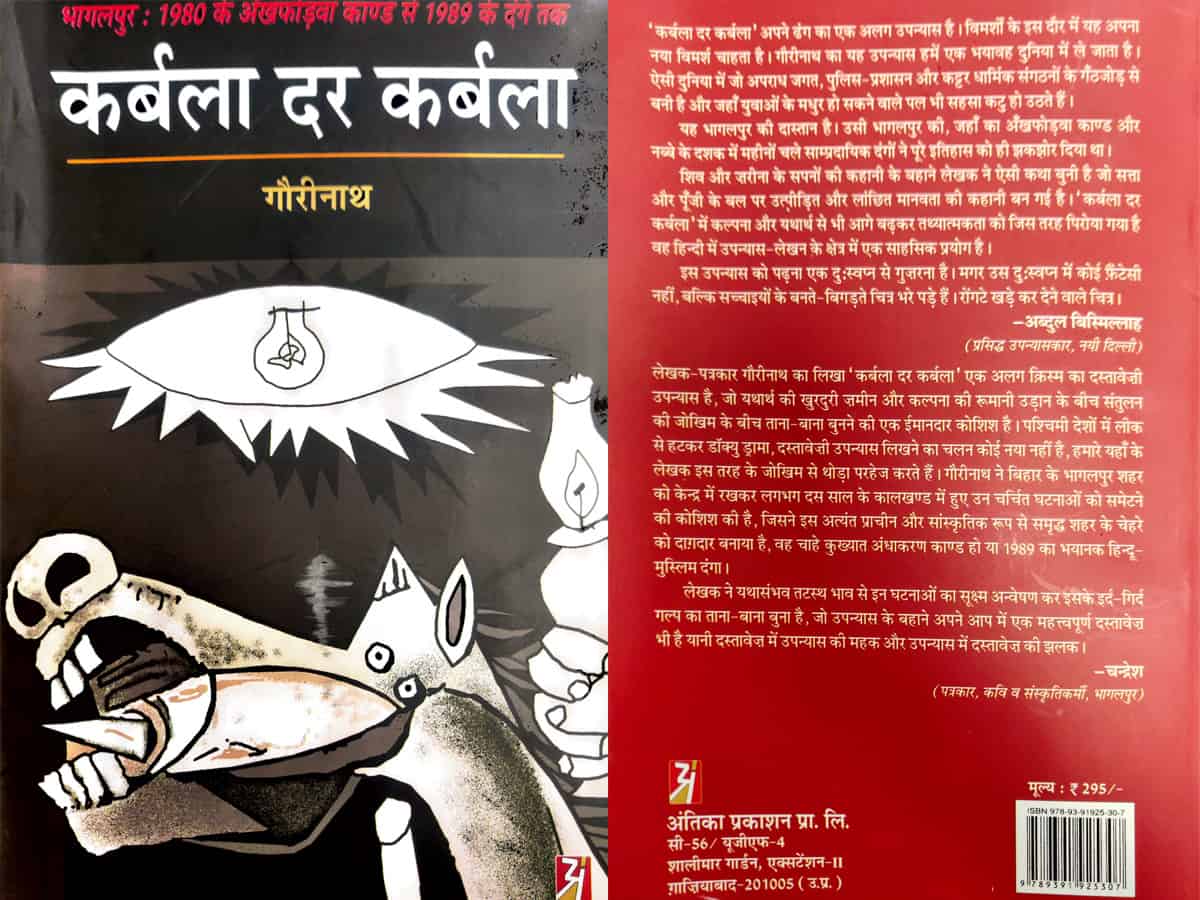

The voice of sanity does make its presence felt in an insane world. The tantalizing and pulsating tale of unrequited and gratifying love is hardly told. A celebrated author of Hindi and Maithili, Gauri Nath nuancedly supplemented what has been missing in describing the city’s eventful history. He creatively upended the popular notion about the city by making it the locale of his gripping novel, Karbala Dar Karbala, which juxtaposes fact and fiction with equal intensity. How does a town known for perfecting the art of mutual butchery set aside the language of hate and revenge? The novel meticulously zeroes in on the question by referring to political betrayal, psychological and sexual violence without rhetorical flourish. The role of religion, nation and cultural aspirations is discussed without valorizing or demonizing it in a mushy manner.

The author lives up to the assertion he made at the outset, “over the debris of horrific massacre I made a faint attempt to fashion a narrative of love.” The novel does portray a society where violence has become an instrument of marking the boundaries of the communities. However, it affords us an insight into the complex nature of the human psyche that cannot turn its back on love. Here one can find a definite shred of resemblance with Garcia Gabriel Marquez’s famous novel, Love in the Time of Cholera (1988).

The novel, divided into 26 concise chapters, portrays the layered and invigorating love story of two adults, Shiva and Zarina. They have been fed animosity for their inherited religion, cultural practices, and mother tongue. Shiva was asked not to mix up with the Muslims. They hardly share common bonds with Hindus though they live in the neighborhood. Shiva always felt disdain for the Muslims as they were considered inimical to Indian cultural ethos and civilization.

Young and naïve Shiva had witnessed the merciless killings of his music teacher and his wife, who said to have been the daughter of a Muslim. The novel begins with the protagonist’s monologues, recalling the gory incident and opinions about Muslims.

“Muslim women are cruel and wicked. He finds this statement indigestible. Are there any real differences exist between Muslims and Hindus? He has been listening to many nasty things about Muslims since childhood. He was told that Muslims do things contrary to how we do it. He also saw that his class fellow Nafees turned pages of his only Urdu books reverse. However, in other subjects, he followed us.

Similarly, in village festivals, he uses the reverse side of the banana leaves. He used to listen to the pernicious maxim about Muslims. Whoever eats beef can never be the friend of Hindus. But, Nafees was not his enemy as he trusted him more, why he was fed with this sort of information about Muslims.”

Gauri Nath writes in Hindi and Maithili with equal ease and ropes in the fictionalized documentary narration of the communal riots that lasted well over a decade (1980-1990). The scourge of communalism perpetuates gender injustice, and religious affinity has no bearing on this count, ‘Many came to deceive Malka Begum, and the most important was a Kashmiri soldier, Mohammad Taj. He married young Malka Begum and left one son and one daughter in her lap, but he fraudulently took away the compensation money given to Malka for the slain members of her family. He deserted Malka.”

The author carries the readers to the site of communal conflagration and astutely tells the stories of those who survived its travails. It is not the run-of-the-mill story of how politicians with the connivance of the bureaucracy become more voracious perpetrators of evil.

The novel has a dig at the attempts to shamelessly use the notion of nation as a veneer for spreading communal hatred at various parts of the country. It is a time when moral values are tossed aside, and the bond of human relationships is in tatters. The society rocked by the violence of communal conflagration desperately needs spatters. The blitz of mindless brutality is to be thwarted immediately. It is a matter of satisfaction that Gauri Nath lives up to the expectations. His astutely narrated novel sets up a veritable fortification against the nefarious design of perpetrators of violence. It is an engaging read, and it is quite rich in references as the author quoted the reports and books on the subject diligently.

Shafey Kidwai is a bilingual critic who got Sahitya Academy Award in 2019 for Urdu. He is professor of Mass Communication at Aligarh Muslim University.