Dunya ne tajurbaat -wa-hawadis ki shakl mein

Jo kutchch mujhe diya hai, lauta raha hoon main

(Whatever the world gave me in the shape of experiments and accidents/

I am returning them to you)

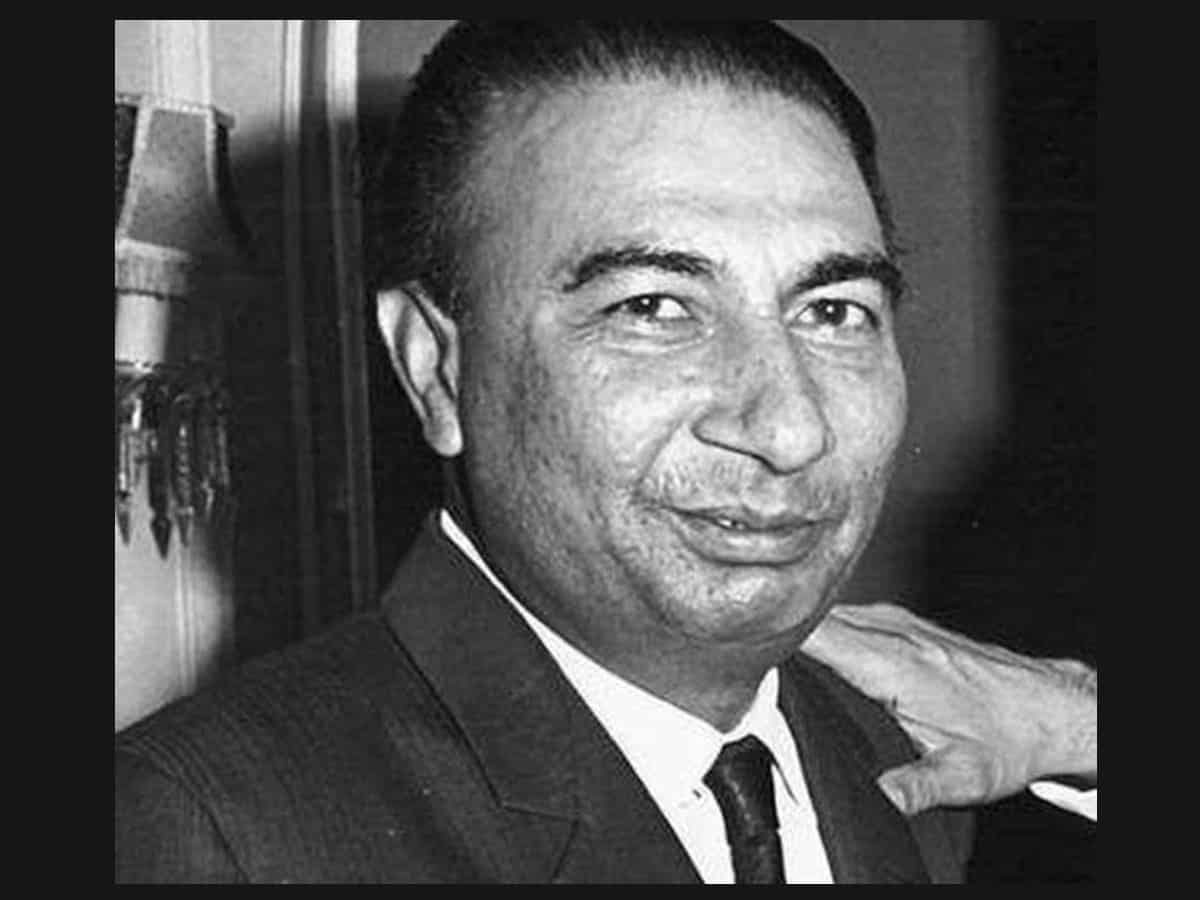

–Sahir Ludhianvi

I never met Sahir Ludhianvi. I was in a village High School in Bihar when he died in 1980 in Bombay. But I knew him, like millions of his other admirers, through his poetry, especially Hindi film songs.

The first time I heard Maine chand aur sitaron ki tamanna ki thi/Mujhko raaton ki siyahi ke sewa kutchch na mila from 1956 film Chandrakanta, it tugged at my heart. The song articulates the universal pain of unrequited love, of a sense of loss at not getting what you long for, at helplessness of painful separation. I will not say if I too had undergone a heartbreak and therefore immensely identified with this song but it led me to search for Sahir’s rich repertoire. To read and hear Sahir is to meet multiple human emotions.

Few poets have brought in so much pathos in such beautiful metaphors. Many poets before him wrote about women and their exploitation at the hands of men. But it is Sahir who could say, Aurat ne janam diya mardon ko, mardon ne use bazaar diya.

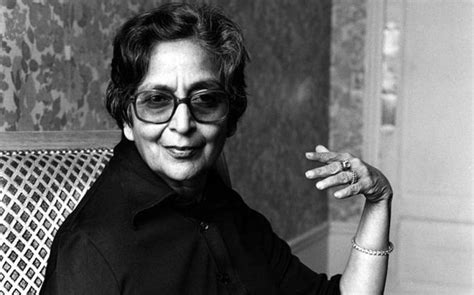

Many women came in Sahir’s life, Amrita Pritam and Sudha Malhotra among them. Pritam writes that once she attended a mushaira where she saw people seeking Sahir’s autographs. Pritam didn’t take a piece of blank paper before Sahir. She, instead, put her palm before him. “This is my signature on a blank cheque. Fill in whatever amount you want and encash it whenever you like,” Pritam remembers Sahir telling her.

Shair’s romance with Pritam and many other women may have been talk of the town once. But, according to Pakistani poet and Sahir’s close friend Ahmed Rahi, Sahir loved just one woman and hated one man. He loved his mother and hated his father.

His father Chaudhary Fazal Muhammed was a big zamindar with several wives. A drunkard, his relationship with Sahir’s mother Sardar Begum was strained. They got separated. Sahir’s father wanted his custody because he was his only male child and patriarchy demands that legacy is bequeathed on male inheritors. But Sahir’s mother fought and won the case, getting his custody. The mother-son duo faced huge hardships, emotional, financial.

Sahir never married and lived with his mother till she died in 1974. If Sahir named his first collection of poems Talkhiyan (Bitterness), it was due to what he and his mother had gone through.

Javed Akhtar gave an interesting interview to Urdu lover and Supreme Court lawyer Saif Mahmood about Sahir for an edition of Jashn-e-Rekhta. In that interview Akhtar says how Sahir took his mother along to wherever he went to attend mushairas. “He would travel to Amritsar, Burhanpur…in car along with his mother,” Akhtar recalls.

One of Sahir’s collection is Parchchaiyan (Shadows). After he moved from Versova to Juhu, Sahir called his new house Parchchaiyan. Theatre director Mujeeb Khan and producer Faruq Nadiadwala who plan year-long celebrations for Sahir are aghast at the sorry fate Sahir’s books met. “The room remained closed for a decade or so as one of his sisters had closed it after Sahir’s death. I was heartbroken to see that termites had eaten away the books. They were not salvageable,” Mujeeb Khan told me when I met him recently. I know at least two eminent literary and film personalities whose personal libraries were orphaned after their deaths. Sahir was one of them. The other was Khwaja Ahmed Abbas. Sahir and Abbas didn’t have the fortune to have children as Harivanshrai Bachchan and Kaifi Azmi had. Amitabh Bachchan and Shabana Azmi not only took care of their parents while they were alive, they also ensured that their books didn’t get orphaned.

A progressive to the core, Sahir protested everything that hurt humanity. Poets have glorified wars and battles. Sahir slammed them. His anti-war poem Aie Sharif Insano powerfully describes the destruction and tragedy wars bring. It argues that jang or war is itself a problem. Jang to khud ek masla hai/Jang kya maslon ka hal degi (War is itself a problem/What solution a war can provide),” he says and suggests that Jang talti rahe to behtar hai (it is better that the war gets postponed).

When Sahir’s relationship with big music directors soured, he paired with directors like Khayyam and gave some of the more memorable songs. Who can forget the soothing, lilting song Suhaag raat hai ghonghat utha raha hoon main/Simat rahi hai tu sharma ke apni baanhon mein (Kabhi Kabhi)? Married men and women get transported to their own nervous, shy wedding night when they hear this song. Sahir never had the opportunity to lift the ghoonghat of his bride, but knew how to capture the scene and mood in words. Words will what keep Sahir alive.

As we celebrate Sahir’s 99th birthday on March 8 which is also International Women’s Day, we must thank God for giving us a wordsmith like Sahir. Our popular culture and literary history would have been poorer without him.

Mana ke is zameen ko na gulzar kar sake

Kutchch khaar kam to kargaye guzre jidhar se hum

(I may not have turned this earth into a garden/I did reduce thorns from the paths I passed)

Mohammed Wajihuddin, a senior journalist, is associated with The Times of India, Mumbai. This piece has been picked up from his blog.