The ruling and the majority communities lived in harmony, the Razakar atrocities being treated as an aberration. Father’s best friends included a number of Urdu-speaking officials and non-officials. At the height of Razakar movement, these people posted a sentinel at our place with an assurance ‘You have nothing to fear, Rao saab, as long as we are around.’

March 26, 1942.

On that memorable Thursday, we (meaning parents and brothers, I was not born yet) arrived at Kacheguda railway station to a strange new world, new people, new culture and an unknown language. We travelled to Secunderabad by Naizam bandi (Nizam’s Train) and then shifted to Bolaram-Falaknuma suburban train.

Our maternal uncle, an engineer at the ordnance factory facing the station, received us, after customs clearance. Two tea stalls, existing side by side, offered ‘Hindu tea’ and ‘Muslim chai’- a sort of cordial polarization. Tongas were everywhere.

Soon we moved to what proved out to be our happy home for 16 long years, Anand Bhavan, skirting Barkatpura chaman (garden). We occupied two of the four flats, Marathi and Tamil families the other two while Kannadigas lived in the outhouse, giving it a cosmopolitan complexion.

Our neighbourhood was peopled by the elite and the reputed. They included Nawab Hoshiyar Jung, Burgula Ramakrishna Rao, Ali Yavar Jung, Shah Alam Khan, Olympian soccer player Lateef, ministers and bureaucrats.

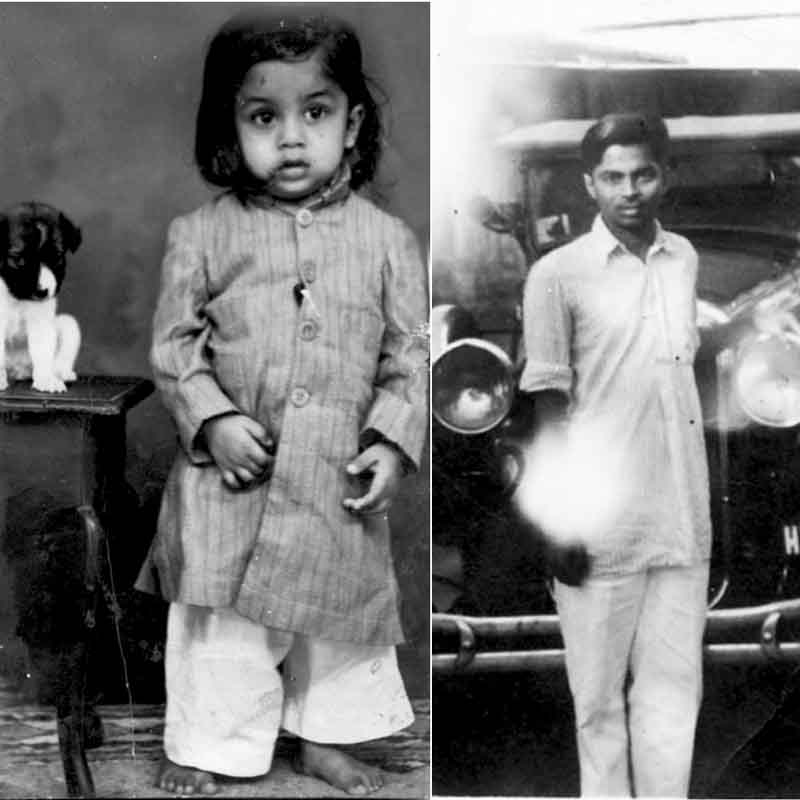

I was born in what is today Badruka College of Arts and Commerce near Kacheguda station. My schooling began at Stanley Girls High School. We kids played in the circular chaman and the chinthala thopu, where the APHB quarters stand today. Sherwani-pyjama was my favourite dress.

Barkatpura those days was a veritable Garden of Eden, dotted with avenue of flower bearing trees, palatial buildings and havelis. It was free of din and bustle. I remember seeing mule-drawn coaches at the havelis of the nawabs. I was told they carried food from the Nizam’s central kitchen. I do not know how true it was.

My brother used to commute to Osmania University by the rokke (stop) bus. The conductor would shout ‘rokke’ to help passengers board or alight at any point. The RTC buses came later.

We had two cars, Ford/ Chevrolet of the 30s and Chrysler convertible of the 40s vintage. The latter was a head-turner, a stunner and a black beauty. Once or twice, we were baffled to find policemen saluting as we drove by. We learnt later that they mistook it for an identical car from the royal stable of such luxury cars as Rolls Royce, Bentley, Daimler, MG etc.

We regularly enjoyed full moonlight or early morning drive to Osmania University to marvel at the majestic Arts College building or to feast on the landscape gardens. Few would believe that the campus roads were carpeted with marigold flowers and dry leaves shed by the avenue trees. The dot neat concrete road from Barkatpura to the University was laid in the forties in a record time for the visit of the Viceroy, Lord Wavell. Even Madras or Bombay did not have the kind of underground drainage system and road network like Hyderabad’s. Nizam College, where my maternal grandfather studied, was affiliated to Madras University.

My childhood remembrances: Jawaharlal Nehru passing in front of our house, Mysore Maharaja Sri Jayachamaraja Wodeyar declaring open Veerasaiva Vidyavardhak (VV) hostel building opposite the RBVR Women’s college and a dying elephant at in the Uttaradi Math in Lingampally.

Mother would often recall how as a child of four I had nearly endangered our lives. Sword wielding razakars roamed the place at night raising slogans. My mother watched the scene through the gaps in the window when, it seemed, I cried ‘amma em choosthunnavu?’ Her blood froze in panic.

The sprawling park in Bagh Lingampally was once a big pond for the nobility to splash about. It abounded with countless tamarind trees presenting an intimidating picture. Our house teemed with relatives from Andhra and my job was to take them to Charminar, High Court, Public Gardens (it had a zoo attached) and the Salar Jung Museum, now relocated on the banks of the Musi.

We had every year Urs, a mini-numaish where small time traders spread their wares on either side of the road stretch between the station and Kacheguda chowrasta. On display were toys, hairpins, clips, lanterns, kitchenware and a variety of fancy goods. Happy faces glowed in lantern light as they scanned the items. The show presented a dazzling nightly spectacle.

We, former Bezwadians, sadly missed idli-karapodi, upma, and dosas. Udupi-type hotels were few and far between, but the quality of food was very poor. Ambis Cafe, opposite Nampally station, was one of the oldest which had survived till the turn of the century.

Rickshaws, bicycles, pets and radio sets were required to have license. Radio licenses were renewed in post offices while Hyderabad Municipal Corporation issued them to cycle and rickshaw owners. This system continued till the early 70s. Kandil points existed all over the city where cyclists refilled their ‘kandils’ with kerosene.

Hyderabad had dual currency system – the British Rupee, also called BG or kaldaar, and the Nizam’s, known as Osmania sikka or haali. We reserved BG for use outside the Nizam’s dominions.

Government offices closed on Friday and the administration was generally free of corruption. It was said you could get your things done by buttering the man with a mere chai and zardawala paan.

The ruling and the majority communities lived in harmony, the Razakar atrocities being treated as an aberration. Father’s best friends included a number of Urdu-speaking officials and non-officials. At the height of Razakar movement, these people posted a sentinel at our place with an assurance ‘You have nothing to fear, Rao saab, as long as we are around.’ Mother would often recall how as a child of four I had nearly endangered our lives. Sword wielding razakars roamed the place at night raising slogans. My mother watched the scene through the gaps in the window when, it seemed, I cried ‘amma em choosthunnavu?’ Her blood froze in panic.

I could go on and on about the city I was born and grew up in. Once a Hyderabadi, always a Hyderabadi. That is its enchanting spell.

Dasu Kesava Rao is a journalist with 50 years of experience, columnist, writer and translator. He retired as Deputy Editor/Chief of Bureau The Hindu, Hyderabad. He had earlier worked in The Indian Express, Deccan Chronicle and The Daily News. He holds Master’s degree in Communications and Journalism. He is 76.