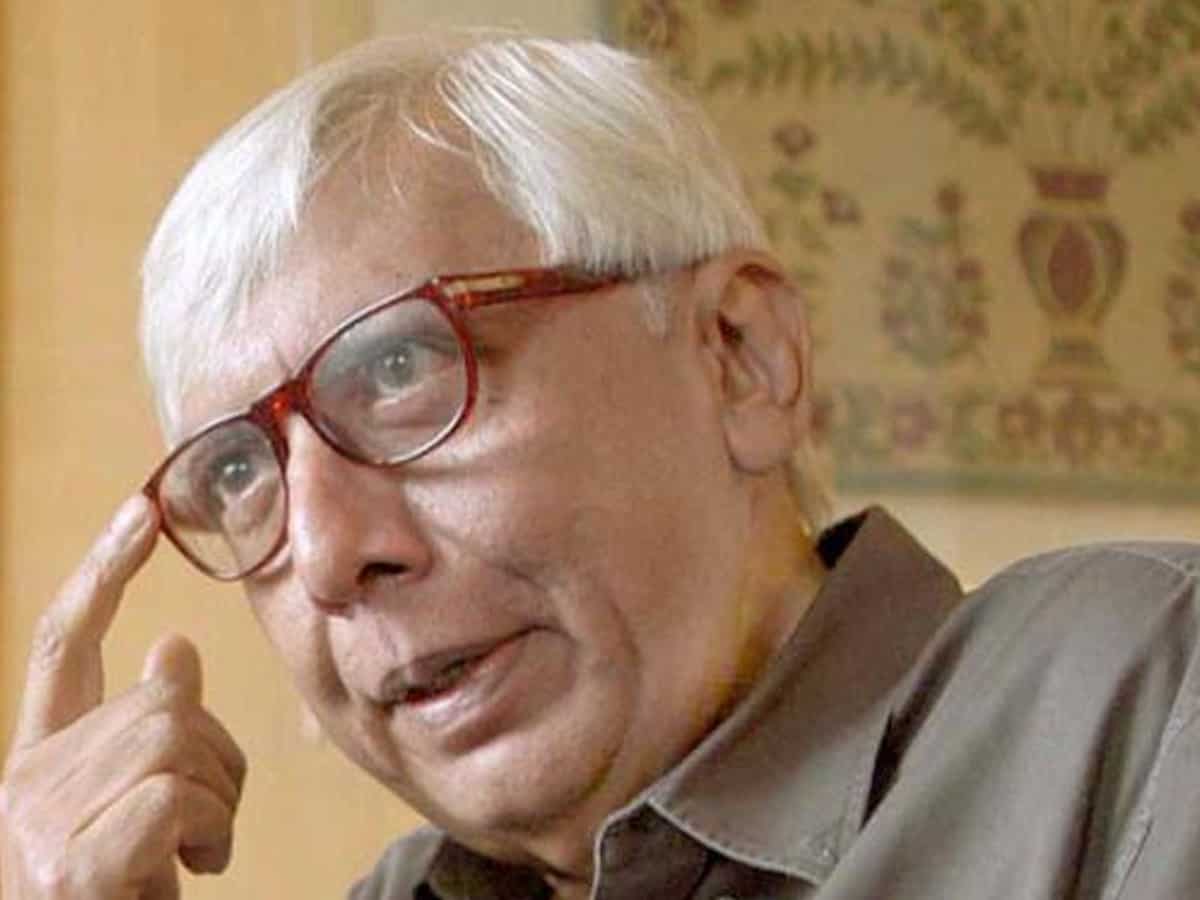

After spotting a reference to the poet Dom Moraes in my article on Ved Mehta, a thoughtful reader wrote to tell me that he owned a copy of Dom’s first book The Grass is Greener (1951). It was published when he was only thirteen years old. Its subject was not poetry, for which he later became world famous, but cricket.

Its frayed dustjacket describes him as possessing ‘an amazing precocity.’ Curiously, Dom never mentions it in any of his autobiographies, except in a casual aside in Never At Home (1996).

At the age of twelve, Dom received his first prize as the best commentator in a cricket match between the Commonwealth XI and India XI in 1950-51. At the age of eighteen, while still at Oxford, he won the more coveted Hawthornden Prize for his slim anthology of poems A Beginning (1961).

Dom, like his Goan Roman Catholic father Frank Moraes (Editor of The Times of India and later Indian Express), thought in English, expressed himself in English, and yearned to live in England. He was forced to survive in an India with a thousand dialects, none of which he understood.

After his spectacular debut at Oxford, Dom spent erratic years, as he said of a fellow-poet, ‘commanding new pyramids of words/ such as he had erected when young.’ The next lines applied equally to Dom’s own life: ‘But Fitzpatrick’s sharp tongue/ had swollen with drink; what had rung like an icicle/now like a clapper with no bell swung: had grown adipose / prosing the days away.’

The first book of his I read was his partly true, partly imagined, wholly mischievous travelogue Gone Away: An Indian Journey (1960) – his version of a journey he made with Ved Mehta. I became an addict. Until I was able to visit India for myself, I saw it primarily through his eyes. His articles leapt me across the world – to New York, Hong Kong, Bhutan, Algeria, South Africa, even deep in the Indonesian forest to shake hands with the unwashed Dani tribe of cannibals.

The list of his interviewees was astonishing: the Dalai Lama, ‘a stalwart young man with rosy cheeks and what seemed a permanent smile’; Mother, now St. Teresa; Philippine President Marcos and his over-ambitious wife Imelda; Bob Guccione (the founder of the soft-porn Penthouse magazine); and the Israeli prime minister (‘The Lion of Judah’) David Ben Gurion.

In 1961, Dom covered the trial in Tel Aviv of the former Nazi SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann trial, whom the Israelis had kidnapped from Buenos Aires in May 1960. Viewing his subject (a symbol of the Holocaust) through a glass partition, Dom described him as ‘very ordinary, a thin man, bald and bespectacled’.

Dom met his journalist’s quota of Indian leaders: I.K. Gujral, Moraji Desai, the Gandhian facsimile Vinoba Bhave whom Moraes interviewed without success on Bhave’s day of silence, and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. To Moraes, Nehru appeared ‘beautiful and sensitive’, until he removed his white Gandhi cap: ‘A grotesque element entered his appearance; he then resembled a bald schoolboy.’

His friendship with Nehru’s daughter Mrs Indira Gandhi swung like a pendulum. Out of power, she encouraged Dom to write her biography. In power, she resumed ‘not one mask, but a series of then behind which her identity lay, quiveringly sensitive’. He finished the book. She disowned it, killing it with ‘an icy stare’.

My wife Shahnaz and I had been admirers of Dom’s writings for years. When in 1996, during a visit to Mumbai, we learned that he and his wife Leela Naidu lived in a flat close to the Taj Hotel where we were staying, we took the chance to meet him.

The entrance to their flat was partially barricaded by a discarded bath tub. We rang the bell. Leela answered. She was no longer the ‘passion flower’, the glamorous actress who had taken Mumbai’s filmy firmament by storm. She looked worn and defensive. Dom emerged reluctantly. He would have preferred not to meet two persistent Pakistanis, however adulatory, but on overhearing our references through the half-open door, he relented.

The next and last time we met him was in the flat of the film-maker Basu Bhattacharya. Gulzar joined us with a tape of Lata Mangeshkar’s freshly recorded song for his film Maachis. Dom had separated from Leela by then. He had the architect Sarayu Shrivatsa as his companion and literary collaborator.

An irredeemable alcoholic, Dom died in 2004, of cancer, on my birthday. The gift he left me and to millions like me are a poet’s feelings, wrapped within words. Whoever has attempted to mount the Bucaphelus of poetry will understand the challenge, as he did, of ‘making the poem, taking the word from the stream,/ Fighting the sand for speech, fighting the stone.’

Fakir S Aijazuddin is a noted thinker and columnist of Pakistan