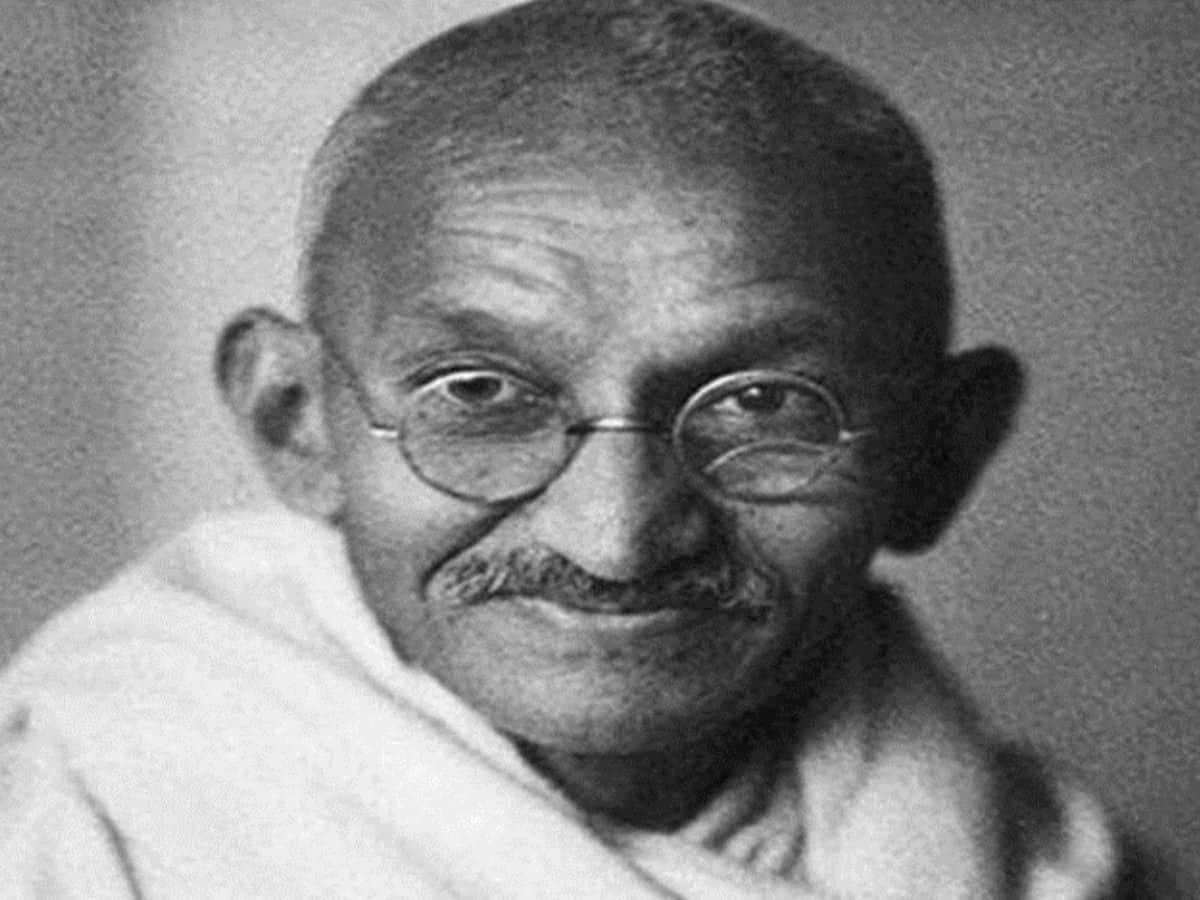

New Delhi: Mahatma Gandhi had returned the prestigious ‘Kaisar-i-Hind’ medal and two war medals to the British as part of his support for the Khilafat movement in 1920, saying he could not wear them “with an easy conscience” so long as Muslim countrymen laboured under a “wrong done to their religious sentiment”.

In a letter written to the viceroy Lord Chelmsford five years after his return from South Africa, Gandhi had criticised the imperial government and said it had acted in the Khilafat matter in an “unscrupulous, immoral and unjust manner”.

An original copy of his letter dated August 2, 1920 and several other rare documents from the long period of India’s freedom struggle are on display currently as part of an exhibition at the National Archives of India here being hosted under the ‘Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav’.

“It is not without a pang that I return the Kaisar-i-Hind Gold Medal granted to me by your predecessor for my humanitarian work in South Africa, the Zulu War Medal granted in South Africa for my services as Officer in Charge of the Indian Volunteer Ambulance Corps in 1906 and the Boer War Medal for my service as Assistant Superintendent of the Indian Volunteer Stretcher Bearer Corps during the Boer War of 1899-1900,” Gandhi wrote in the letter.

Gandhi and his wife Kasturba returned to India from South Africa on January 9, 1915 and were accorded a warm reception by the people.

The same year he was awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind gold medal in the King’s birthday honours list, according to the official website of a Gandhian institution, Bombay Sarvodaya Mandal.

He was decorated with the Kaisar-i-Hind medal by the then viceroy Lord Hardinge who is known to have admired the ideals espoused by Gandhi.

In the 112-year-old letter neatly preserved at the National Archives, Gandhi further writes: “I venture to return these medals in pursuance of the scheme of non-cooperation inaugurated today in connection with the Khilafat movement.”

“Valuable as these honours have been to me, I cannot wear them with an easy conscience, so long as my Mussalman countrymen have to labour under a wrong done to their religious sentiment”.

“Events that have happened during the past month have confirmed me in the opinion that the Imperial Government have acted in the Khilafat matter in an unscrupulous, immoral and unjust manner, and have been moving from wrong to wrong to defend their immortality. I can retain neither respect nor affection for such a Government,” wrote Gandhi, who would later go on to lead the freedom movement that would see the birth of an independent India on August 15, 1947.

His return of the medals also came a year after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar on April 13, 1919 where people had gathered to protest against the government’s Rowlatt Act.

In the letter, Gandhi also wrote that the attitude of the Imperial and Your Excellency’s Government on the Punjab question has “given me additional cause for grave dissatisfaction”.

Gandhi further mentioned that he was “one of the Congress Commissioners” to investigate the “causes of the disorder on the Punjab during the April of 1919”.

“And, it is my deliberate conviction that Sir Michael O’Dwyer was totally unfit to hold the office of Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab and that his policy was primarily responsible for infuriating the mob at Amritsar.

“No doubt the mob excesses were unpardonable, incendiarism, murder of five innocent Englishmen and the cowardly assault on Miss Sherwood,” he wrote in the letter.

The exhibition also has on display another archival document, containing the text of the original rare letter dated May 31, 1919 and written by legendary poet and Nobel Rabindranath Tagore to the then viceroy, requesting that he may be relieved of his title of knighthood after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

“The enormity of the measures taken by the Government in the Punjab for quelling some local disturbances has, with a rude shock, revealed to our minds the helplessness of our position as British subjects in India.

“The disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the methods of carrying them out, we are convinced, are without parallel in history of civilised governments, barring some conspicuous exceptions, recent and remote,” Tagore wrote.

In the same document, a portion below the letter refers to another correspondence dated June 2, 1919 from “Associated, Calcutta” to “Mr. Buck, Simla” and it says that the newspaper “Englishman has received a copy directly from Tagore and is publishing full text”, and Tagore has also sent vernacular version to Indian press which will probably publish.

The exhibition titled — ‘Saga of Freedom: Known and Lesser-known Struggles — was inaugurated on August 12 by Union Minister of State for Culture Arjun Ram Meghwal.

Spanning a period of over 200 years, these original archival documents and pictures chronicle various revolts and freedom struggle during the colonial rule, and have been exhibited to mark 75 years of India’s Independence.

Over 100 original records have been put on display, including on the Indian Independence Act, 1947, and a letter from P R Lele to the Secretary to Government of India regarding Independence India Bill dated July 15, 1947.

“Majority of the archives are being displayed for the first time, and are extremely rare,” NAI’s Director General Chandan Sinha had told PTI earlier.

Archives related to Rampa Rebellion (1922-1924), whose centenary was marked on Monday, are also part of the exhibition.

Alluri Sitarama Raju had led an armed rebellion, popularly known as Rampa rebellion with an attack on Chintapalle police station on August 22, 1922 in Vishakhapatnam.