An in-depth look at how Bengal went from ‘Laal Salaam’ to ‘Jai Shri Ram’ in the space of less than a decade. From being a fringe political party in 2013 to sweeping nearly half of the states 42 Lok Sabha seats in 2019, the BJP has gained ground in West Bengal, aided partly by the RSS’s exponential growth during Mamata Banerjee’s chief ministerial tenure (2011 onwards).

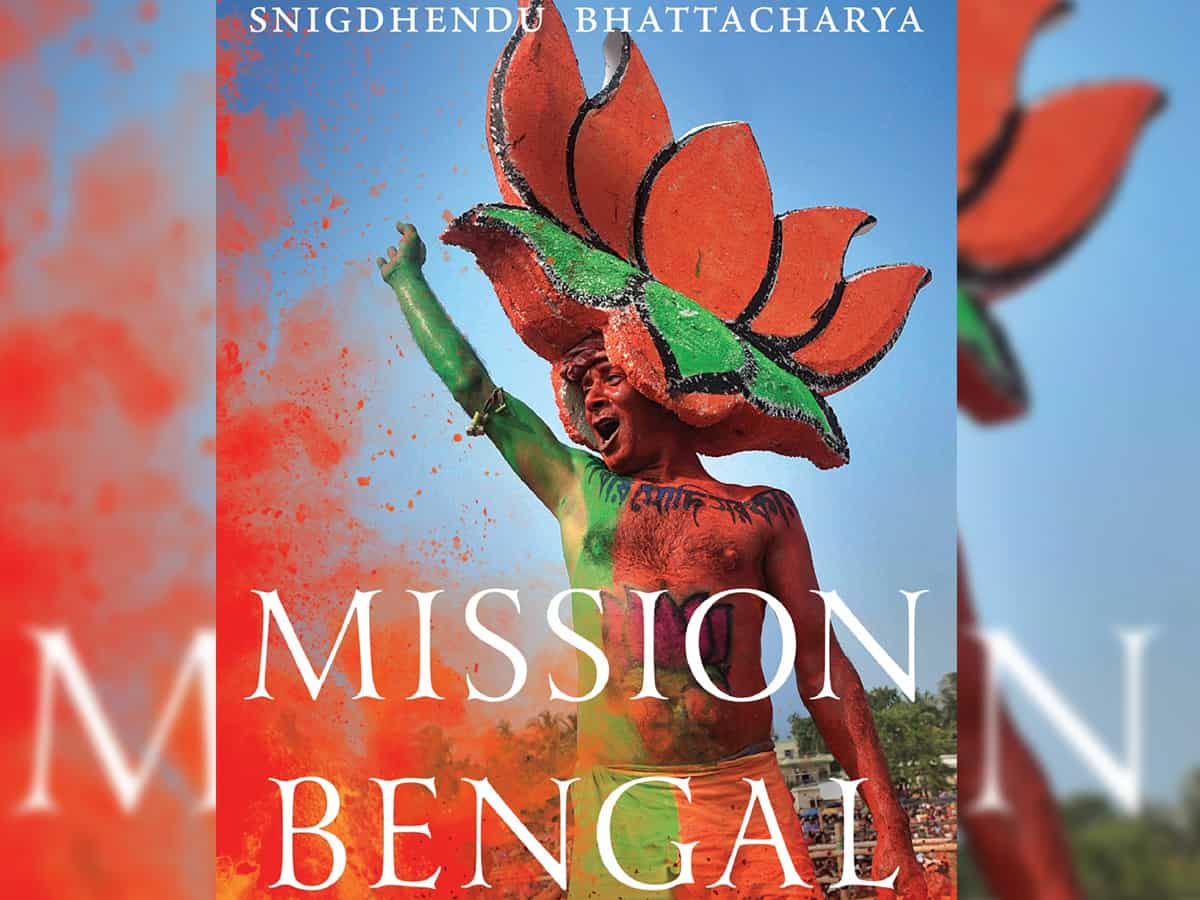

“Mission Bengal” by Snigdhendu Bhattacharya documents the BJP’s extraordinary rise in the state and attempts to look at these developments in the historical context of Bengal — from the rise of Hindu nationalism and Muslim separatism in the 19th century, the Partition and its fallout, the impact of developments in Bangladesh, the influence of leftist ideals on the psyche of the Bengali people, and the demographic changes in the state over the past few decades.

Here is an excerpt:

The Trinamool Congress was changing and Prashant Kishor was the change agent. If the BJP was gaining from the work of the RSS, the TMC was gaining from PK’s I-PAC. Mamata’s trust in PK’s ways of working increased manifold, and PK started emerging as one of Didi’s top confidantes after the party’s assembly bye-election success.

So, what did PK advise Didi? According to a senior minister, who wished to remain anonymous, PK told the TMC top brass that four things were essential — administrative delivery, a vibrant party organization, ideological consistency and a clear perspective on what went wrong and how.

The first two aspects were covered under the elaborate, three-tier grievance redressal system, involving the grievances monitoring cell at the chief minister’s office, the Didike Bolo helpline, and the survey teams of I-PAC that travelled the state’s length and breadth, inquiring from the common people, grassroots-level TMC workers, panchayat members and municipal corporators their perception about administrative delivery and the reputation of local TMC leaders. There was synergy between the three tiers.

‘Didike Bolo’ helpline was used by the people to complain about anything and everything — from administrative affairs to the TMC’s internal matters. The complaints were verified and acted upon. It is not that all problems were solved, but as the reach of the programme expanded with time, newspapers, TV channels and news portals were reporting an increasing number of success stories. A youth who lost a leg in an accident got a job in the education department; poor parents got their children enrolled in schools; distant villages got roads and footbridges; slums got improved sewerage and drainage systems, ambulances were booked for critical patients and pregnant women, and so on. It became the general helpline for the people.

Besides, four major policy decisions were taken based on large-scale demands: institution of a monthly pension scheme of Rs 1,000 for senior citizens from the SC and ST communities, a housing scheme for tea garden employees, relaxation of norms for obtaining caste certificates, and limiting transfer of school teachers to within their home districts.

There was another significant change — the TMC had a special focus on the backward classes, who made more than one-third of Bengal’s population of 9.03 crore, according to the census of 2011. Hindus formed 70.54 per cent of the population, with the share of the SCs being 23.5 per cent of the whole population and the STs being 5.8 per cent. Even though the OBC population did not feature in census data, the state had a 7 per cent reservation for OBCs in jobs and education before Muslims too were brought under the OBC category in 2013. From a demographic perspective, Bengal was an ideal state for winning elections based on Dalit-Muslim political unity, with the two communities making up 50.5 per cent of the state’s population.

‘PK told us that we needed to solve the mystery of why the backward classes, especially the SCs, were in general voting against the BJP all over India but in favour for them in West Bengal,’ said the TMC minister. ‘PK’s explanation was that corruption and highhandedness on the part of TMC leaders had hit the backward classes most, as they made the lowest strata of society and were easy prey.’

This author, however, had a feeling that Dalit votes turned towards the BJP not only because of the TMC’s malpractices and highhandedness but also because of the RSS’ social work. The RSS in Bengal had the state’s backward regions dominated by the backward classes as their focus areas for myriad social work, penetrating the society deeper than what the TMC perceived.

(An excerpt from “Mission Bengal: A Saffron Experiment” by Snigdhendu Bhattacharya, published by HarperCollins.)