Rizwan Ahmad

Over the last fortnight, both social media and mainstream publications have been filled with news about how hundreds of cases of Covid-19 across India can be traced back to people who attended an event in Delhi organised by a Muslim organization called the Tablighi Jamaat early in March. Many of the allegations against them have now been found to be baseless.

While even sympathisers of the Tablighi Jamaat note that the organisers were ill-advised and irresponsible in failing to cancel the event, Hindi and English languages newspapers have reported on the incident using vocabulary that vilifies the entire Indian Muslim community. Such hateful representations will have serious consequences not only for India’s ability to fight the pandemic but also to preserve its social fabric.

Following Narendra Modi’s abrupt announcement of a 21-day nationwide lockdown on March 24, people across India were stranded as transportation services were suspended. In addition to the Tablighi Jamaat members who had not yet left Delhi’s Banglewali Masjid Markaz after the event, Hindus and Sikhs in other places were also affected.

In Delhi’s Majnu Ka Tilla gurudwara, approximately 200 Sikhs were stuck. In Jammu city, approximately 400 Hindu pilgrims who had visited the Vaishno Devi were unable to proceed home after train services were cancelled. However, the media used different linguistic devices and strategies in the reporting of these three similar humanitarian crises.

Different words, different narratives

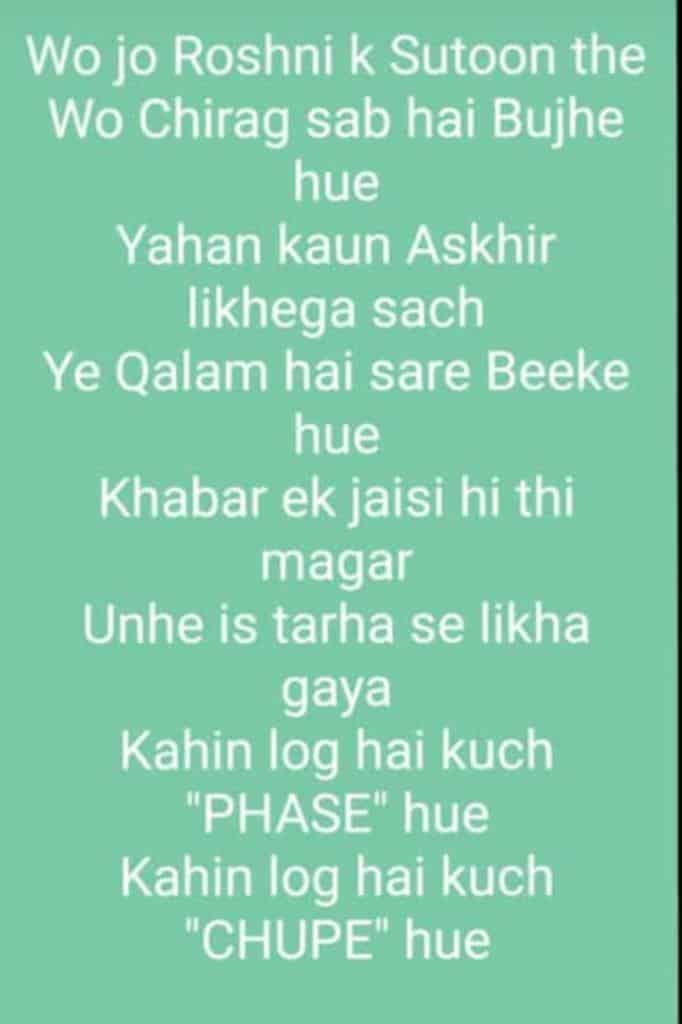

Muslims who were stuck in the Nizamuddin mosque were described by Hindi news portals and newspapers using the word chhupe hue, meaning “hiding”.

As this headline on Zee News said, “113 people hiding in 8 mosques; had attended Nizamuddin Markaz.”

The intransitive verb chhupna, in Hindi means to go to a place where no one can see you. Although this word semantically could have a neutral meaning in certain contexts, such as in the word chhuppa-chuppi, hide-and-seek, it mostly has a negative overtone. People hide either because of someone’s fear, or because they are trying to escape someone. For example, one can say, police ko dekhkar chacha chhup gae, “having seen the police, my uncle hid himself”.

The word is often used to refer to criminals hiding from the police to escape an arrest; it is also used to describe a situation when gunmen hide to launch an attack. For example in this news report, the word chhupe hue is used to describe how the dacoit Mahindra Pasi and his gang were hiding in the Dashahra ghati.

The use of this word in the headline by Zee news to describe the Muslims at the Markaz insinuates that the Jamaat members were engaged in some unlawful, even criminal activity, and were using the mosque as a safe haven.

The Hindustan Times adopted the same linguistic strategy in its headline, “Covid-19: 600 foreign Tablighi Jamaat workers found hiding across Delhi, and counting.” The English word “hiding” captures the same semantic range and has similar contextual resonance as the Hindi word chhupe hue.

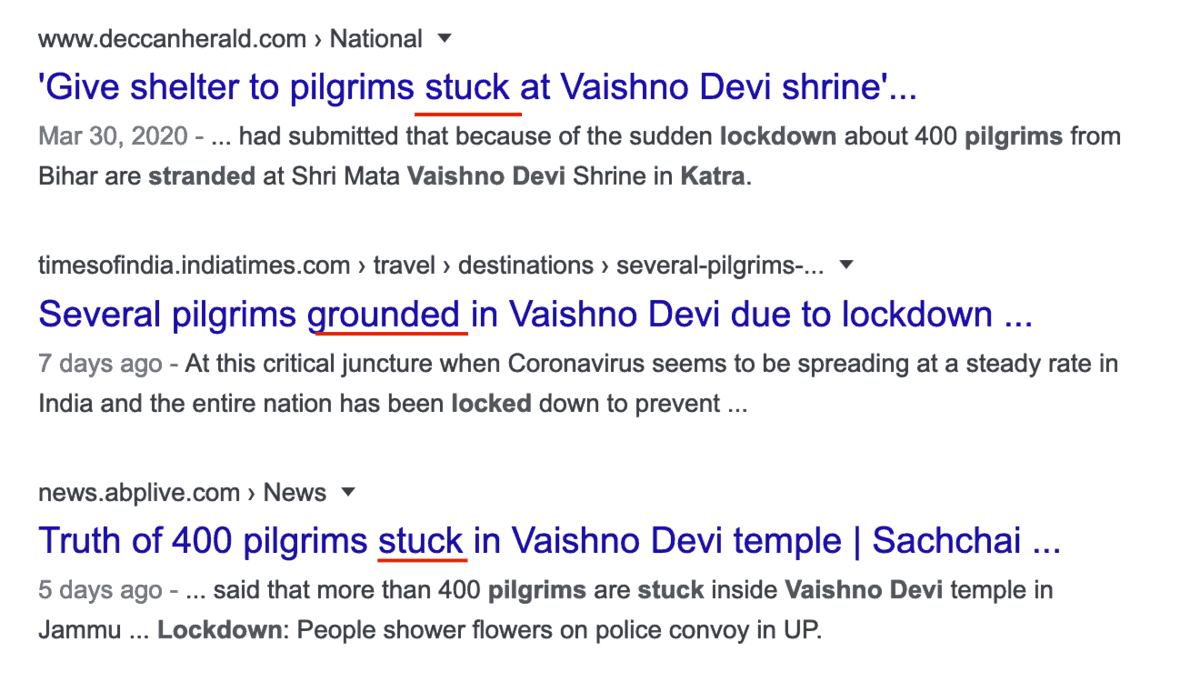

Contrast this event with a comparable event in the same week relating to the Vaishno Devi temple and the Delhi gurudwara. In these cases, most publications chose another word to describe the situation of pilgrims there: phanse hue, which means “trapped”, “stranded”, or “stuck”.

As this NDTV headline says: “Coronavirus lockdown: 400 pilgrims stuck in Vaishno Devi, court orders help for them.”

The assumptions behind the use of the words are quite different: unlike chhupe hue, the word phanse hue is used to refer to innocent people getting trapped in a bad situation by circumstances beyond their control. For example, Hindi speakers would say, “Log jam mein phanse hue the”, people were stuck in a traffic jam.

English publications also used words such as “stranded”, “stuck”, and “grounded”.

Words, as we well know, leave an impact on the audience. While the words “chhupe hue” and “hiding” used for the Muslims in the mosque evoke the reader’s disapproval and anger towards the Tablighi Jamat event, the words “phanse hue” and “stranded” used to describe the Hindus and Sikhs make the reader feel bad about their predicament and create sympathy for them.

For linguists, this episode is a perfect example of how language can be deployed to achieve narrow political goals

It is clear that the vocabulary used to describe Muslims at the Markaz created a narrative in which Muslims trapped in a mosque because they were not able to leave because of travel restrictions are perceived as criminals. Language is more than a tool of communication. It is a double-edged sword. It could be employed to unify and serve the broader interests of the country, or it could be used to distort and manipulate events to serve narrow political interests.

Rizwan Ahmad is an associate professor of sociolinguistics in the Department of English Literature & Linguistics at Qatar University.