In November 2016, as Donald Trump triumphed at the presidential polls, in faraway Minnesota an unknown Muslim woman of Somali origin, Ilhan Omar, also won a seat – to the lower house of the state legislature. Since then, in strange, even ironical, ways, the careers of these two very different political figures have frequently collided – they reflect the deep polarisation in US politics and the fierce ongoing struggle to accommodate within the fabric of the world’s oldest democracy diverse communities – immigrant, black, woman, Muslim, Somali.

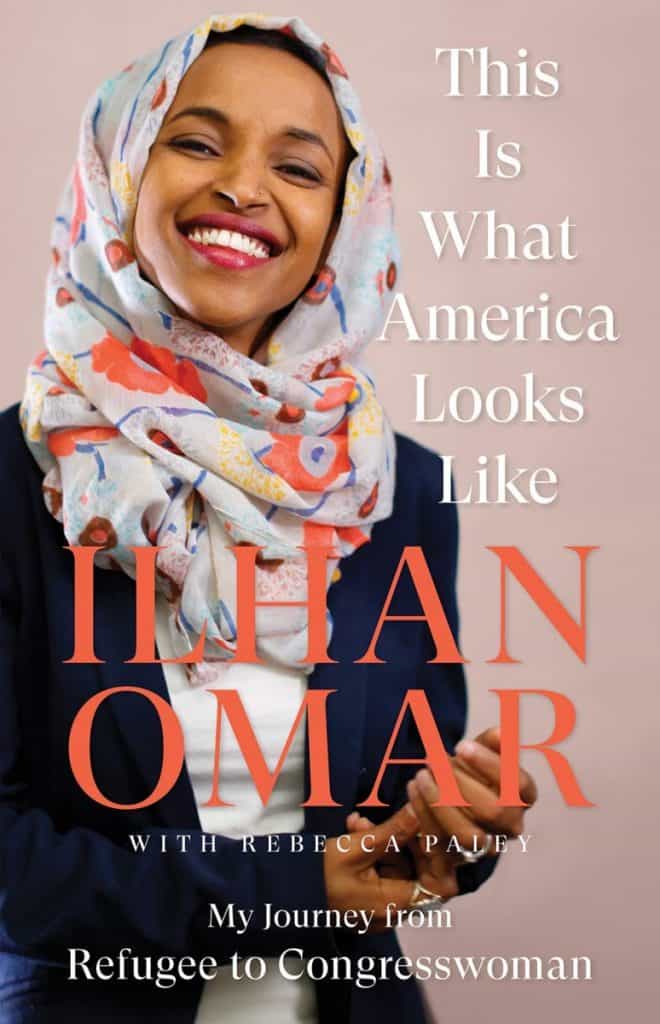

Ilhan Omar is all five. Her book, This is What America Looks Like, is the story of how a young woman from war-torn Somalia, who spoke no English, made her way as a refugee to the US and, within a few years, found herself an elected congresswoman in Washington DC just when the country was rejecting mainstream politics and was voting a racist, misogynist and a bigoted, self-absorbed narcissist to the White House.

This book is our first introduction, in Omar’s words, to her personal and political journey to the US and her experiences as she combated hate, prejudice and cultural divisions to clear her way to Congress in the era of Trump.

Given the civil conflicts that have raged in Somalia over the last 30 years, it is difficult to recall that there was a time when there was peace and normal life in the country. Omar, born in 1982, describes a life of middle-class comfort, with father, grandparents and numerous aunts and uncles making up for the absence of her mother, who passed away when Omar was just two.

This home had books on history and politics and robust discussions on all matters of contemporary interest. Unlike a normal Somali home, no distinction was made between men and women – everyone had a voice and opinion which could be freely expressed. Omar describes herself as both opinionated and aggressive; in school, she stood up for the underdog and beat up bullies.

The civil war from 1991 brought this idyllic life to an end. As state order broke down, the battles were between militants divided on clan and sub-clan basis that made enemies of old neighbours and companions. As Omar thoughtfully points out, this was no different from earlier situations in Nazi Germany, and later, in Rwanda, “where one day you’re all family and next day some members no longer have the right to exist”.

Omar’s family became refugees in Kenya, living in squalid camps, surrounded by disease and death. Her much-loved aunt died before Omar’s eyes. Here, again, the family benefited from immigration quotas provided by some western countries. From among Norway, Sweden, Canada and the US, they selected the US as their migration destination. This was based on her father’s conviction that, while in all other countries they would remain ‘guests’, “only in America can you ultimately become an American”.

Thus, in 1995, Omar’s family found itself, first in Arlington, Virginia, and then in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

She goes on to talk about the early travails in her life, as she encountered new and strange situations, particularly at school, where she spoke no English and was the object of some bullying. She also speaks of the impact of migration on the home environment – when earlier her father had been an easy-going liberal, now, under the influence of the “elders” of the local Somali community, he insisted on more conformity and discipline from her, just when she was entering her rebellious teenage years.

A slow settling down

There was obviously a slow settling down and adjustment to the new culture, possibly the shaping of a new identity that would accommodate Somali traditions with US norms and practices. She soon found love, marriage and motherhood and also a deeper understanding of her faith and how she intended to practice it. Wearing the hijab from 2005 became a major issue – it marked out her identity as a Muslim in an overwhelmingly white, Christian community.

She seems to have reflected on this subject quite deeply; she says: “I need to cover pieces of myself to preserve who I am and feel whole. … [The hijab] connects me to a whole set of internally held beliefs.” The hijab remained a constant factor in her public life, culminating in Congress having to repeal a law from 1837 banning headgear from the chamber to enable her to take her seat.

Omar describes an “early midlife crisis” in her 20s, when she separated from her husband and cut off ties from all her family members. In this traumatic period, she found refuge and recovery in North Dakota State University, where she studied subjects that were new for her – politics and international studies. Higher education healed her and enabled her to re-engage with her family.

Ilhan Omar was now ready for the next big leap in her life: politics.

As she plunges into politics in Minneapolis, she provides an excellent view of the functioning of politics at grassroots: whether they relate to elections at municipal, state or national levels, all elections demand that larger issues be explained to the electorate in terms that make sense at local levels. All elections require that people are motivated to vote, given that the US has among the lowest voter turnouts in the world. And, all elections must have candidates with extraordinary stamina and very thick skin, and dedicated and indefatigable staff support.

Omar – woman, African, Muslim with a hijab – became a larger-than-life presence at all levels of politics. Politics makes you a part of the larger political machine, where you have to be accommodative of people you don’t like and whose views you don’t share. Race and gender are perennial factors in all US politics, as are smear campaigns, hostile media and even physical attacks. Omar experienced all of this – and more.

The greatest opposition to her candidature for state congress came from Somali “elders” in Minneapolis, who could not accept the idea of a Somali Muslim standing for elections – they insisted on a male candidate, even though that person had been unsuccessful earlier.

She herself endured a smear campaign relating to her personal life that also implied that she had come into the country fraudulently. This led several Somali leaders to advise her father to get her to withdraw her candidacy and look after her children.

Omar also experienced a vicious physical assault during the campaign. She is now philosophical about this; she takes comfort in the fact that “the system I fought against [got] dismantled by people who used to feel so small but know now they too can be big”.

The counter-narrative to Trump

Ilhan Omar was a congresswoman in Minnesota in 2017-19. Surprisingly, even then, she, a first-time congresswoman in a state assembly, was seen as a “counter-narrative” to Donald Trump. During the campaign in Minneapolis, Trump had singled out Somalis for abuse, saying: “A Trump administration will not admit any refugees without the support of the local communities where they are being placed. It’s the least they could do for you. You’ve suffered enough in Minnesota.”

Within a few days of entering the White House, Trump signed an executive order to block and ban visitors, refugees and immigrants from seven predominantly Muslim countries, including Somalia. Omar took a firm public stand against the president and overnight became a national personality. In her words:

“The number of requests that came into my office from day one was unprecedented. Global travel, speaking engagements, interviews: they stacked up. Media outlets from around the world, which tracked our press releases and my movements, constantly asked for comment.”

Omar, reflecting the US’S polarised politics, became Trump’s nemesis to such an extent that he began to launch personal attacks on her. In the summer of 2019, in a rally in North Carolina, Trump accused her of being anti-Semitic, supporting Al-Qaeda, and looking down on “hardworking Americans.” This evoked the chant from Trump’s delirious supporters: “Send her back!”

Ilhan Omar also came to be targeted by the pro-Israel lobby in the US. When she decried “political influence” that promoted allegiance to a foreign country, she was condemned for anti-Semitism, but she held her ground. In May 2019, pro-Israel protestors in New York called for her removal from the House Foreign Affairs Committee, with the war cry, “Ilhan Must Go!”. In August 2019, Trump said publicly that Omar and fellow (Muslim) congresswoman Rashida Tlaib “hate Israel and the Jewish people”, which led Israel to ban their visit.

But she has also made a mark among ordinary Americans. In ‘post-it’ messages, several of them have called her variously: brave, bold and outspoken; voice for those who cannot speak for themselves; soldier of peace and justice for all, and simply “an American hero”. But, again, in the run-up to the 2018 midterm elections, out of 113,000 tweets about Muslim candidates, 90,000 referred to Ilhan Omar – these were hate-messages referring to Muslims as subhuman and Trojan horses for imposing Shariah in the US.

Leaves one wanting more

Omar’s is truly a remarkable success story. But, at the end, the book leaves one wanting more. There is a lot of “me, me, me” through the book, but no flesh and blood to the narrative. After the early encounters with her family in Somalia, most of them disappear from the story. Besides an occasional glimpse of her father and once or twice of her sister, we get to know nothing about her siblings, though her biography tells us she is one of seven children.

Even her first husband, Ahmed, remains a shadowy figure, making rare cameo appearances to prop up her career and then disappearing. We know that they separated during the “meltdown”, but reconciled later; we know nothing about when they divorced. Her second husband is not even named; we are simply told it was a short-lived mistake, part of her meltdown. We know from her bio profile on the internet that she married for the third time, in 2020, but there is no mention of this person in the book.

A serious omission is Omar’s failure to discuss frankly the criticisms directed at her relating to her two marriage licenses and allegations of immigration fraud. Given the US’s toxic electoral politics, the scrutiny of all candidates’ personal lives and, above all, the fact that President Trump has personally waded into this issue, the book would have been a good place to clarify matters.

We are told references to the two marriage licenses are true, but how they relate to immigration fraud is just not discussed, beyond a cryptic reference to a conspiracy theory about her marrying her brother! The absence of candour on this important and sensitive issue is worrying, particularly as Omar prepares for her second run for Congress later this year.

Also a notable lapse is the silence relating to her first year in Congress. She devotes several pages to her induction – when the police officer doing the briefing, either deliberately or inadvertently, thought her male, white aide was the Congressperson and totally ignored her. While we learn a lot about the tactics of election campaigns, we are never told about where she stands on specific issues – in fact, we have to go to the internet to find out that she supports a living wage, universal healthcare, affordable housing and student loan forgiveness.

She also does not mention “The Squad” – the group in the current Congress made up of Omar and three other congresswomen – Ayanna Pressley, Rashida Tlaib and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – which is part of the “progressive” caucus in the Democratic Party. It would have been interesting to learn about these other women who have collectively shaken US politics in the age of Trump, emerging as his nemeses and projecting an alternative view of America to its citizens.

Lacking insight into Americans agitating today

While Omar evokes the frenzy surrounding electioneering, the striking absence in the book is any reflection on her part. We learn nothing about the larger political, economic and cultural issues that are agitating Americans today: the sense of exclusion and marginalisation among poor white Americans, rising economic inequality and the racial divide, the “me too” movement and feminism in our times, the erosion of democracy by special interest groups – none of these are given any serious attention.

Thus, the book fails its title, This is What America Looks Like, since no mirror is held up by Ilhan Omar before this diverse and complex polity. She focuses only on the second part of her title – her journey from refugee to congresswoman.

This book is clearly a curtain-raiser for her forthcoming election campaign and is meant to provide a glimpse of the human person behind the congresswoman. What we do get is still quite interesting.

It sets out a personal journey and political manifesto of a young woman – black, Muslim and Somali – who landed in the US 25 years ago, and, after severe trials, created space for herself in the corridors of power and influence in the American capital. This space is not in mainstream politics, but on the progressive fringes where unpopular causes are agitated, hostility and abuse are generated, your friends and community are often alienated from you, and the wrath of the president himself is directed at you to curb your enthusiasm, dilute your support and silence your voice.

Ilhan Omar has taken only the first steps in the long journey to make the US more humane, more caring. She has a long way to go.

Talmiz Ahmad, a former diplomat, holds the Ram Sathe Chair for International Studies, Symbiosis International University, Pune, and is consulting editor, The Wire.