By Vishnu Makhijani

By Vishnu Makhijani

New Delhi, Oct 17 : Its not easy following in the footsteps of the late Fateh Singh Rathore, Indias legendary “Tiger Man” who virtually single-handedly created and put on the world map the Ranthambore National Park in Rajasthan that is today home to upwards of 60 of the felines out of a total country-wide population of close to 3,000; or for that matter, conservationist Valmik Thapar, who has produced a range of TV programmes and authored 14 books on Indias wildlife, principally tigers.

Fine art photographer, author and entrepreneur Arjun Anand thus had his work cut out for him when he set out to find his muse in Ranthambore, having been first introduced to the wild in the mid-1980s during his family trips to the Bandhavgarh National Park in Madhya Pradesh. It was, however, in Ranthambore that constantly lured him with its myriad offerings.

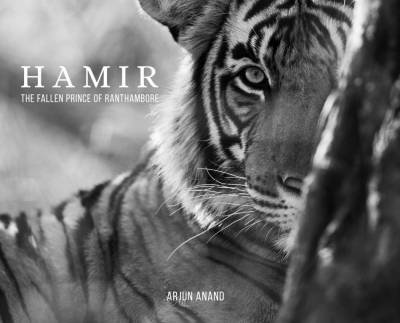

The outcome is “Hamir, The Fallen Prince of Ranthambore” (Pirates India) that with its 160 images, the majority on stark black-and-white and some in colour brings alive a whole new generation of tigers – all of seven – who are taking forward the legend of Machali (1996-2016), The Queen of Ranthambore and perhaps has most photographed tigress in India.

Along with his raw natural talent, what also helped is that Anand is constantly experimenting with his work, incorporating principles of minimalism, grunge (images with dark, dirty, old, gloomy and eerie vibes), and the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi (a world view centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection).

Black-and-white is his medium of choice for its timelessness and the ability to remove distractions of colour, enabling the viewer to better connect with the subject. Even in the jungle, surrounded by the chaos of nature, Anand seeks to capture the stillness and calm of life to create an emotional experience for the viewer – with his penmanship contributing in no small measure.

Sample this:

“I orient my ears toward the rustle. In the distant foliage, I hear not a roar but a breath, and I wish I had something more than my humble shooting machine to save my life. My heart pounds and I tighten my grip on the camera. And without a warning, tearing the leaves apart, pounces out from the dark, the magnificent creature of black and yellow stripes. I forget my dread for a moment and surrender to the regal presence. And then the Prince roars. And flashes its dagger-like-teeth…”

The Prince, of course, is Hamir, to whom is devoted the longest of the nine chapters and the largest number of images.

“Hamir is the reason for this book. He is very dear to me. It is through him that my hobby turned into an obsession…While following him on his journey, I have discovered myself. Hamir taught me to fear the Royals. He showed me the true ferocity of these tigers. And the moment I saw him, it was the beginning of a beautiful friendship,” Anand writes.

“I was fascinated by this little guy. He was something else, unlike anything I had seen so far! The following months I returned in search of him but could not track him or his mother down so I changed my focus to some of the other tigers. At that point, the monsoon season had started and the Park was closed for the next three months. The wait was painful, I wanted to get back out there in search of the young one. I had seen my fair share of cubs over the years and the Royals are usually quite regal in their dealings with us, even the babies. But there was nothing tame about this cub. I was eager to follow him,” Anand writes.

He then cites one particularly memorable encounter.

“It was getting late. We were heading back to the gate, when I spotted some stripes in a bush. I told the driver to stop. As soon as we stopped, the stripes came onto the track. Enter Hamir.

“He snarled at us. I liked that. He then proceeded to sit in front of the vehicle, staring at us. Closing time was upon us and we had to leave soon to avoid incurring a penalty, but the tiger had blocked our path. I was completely overwhelmed by the sight in front of me. Even by the sparse light of the setting winter sun, the light blue of his eyes shone brightly. It felt like he was sizing us up. For as long as Hamir wanted me there, I was his, standing there, enthralled.

“Moments later, he was up and off, but not before snarling at us once more. We rushed to exit the Park, but I was in a trance. I was still basking in the glow of those piercing blue eyes. I was in love. I always wait for the animal’s gaze to meet my eyes; it makes it real for me. But with Hamir it wasn’t some blank stare or absent glance. He was observing us. He was trying to understand us, and I wanted to know him. To me, his snarls were like greetings, one at the start and one as we parted. At long last, my muse had led me to a real tiger. A tiger with fire.

“What followed was a love affair for the ages. If tigers were the Royals, then Hamir was the Prince. And not just any prince, he was the blue-eyed Prince of Ranthambore.”

Anand then takes the reader through a series of stunning visuals that record Hamir’s growing up process.

“I was bemused by his behaviour. I felt like he knew me. Over the next couple of encounters, this became our ritual. We would spot him. He would see us and snarl. It was an eerie comfort for me, a sort of validation of our acquaintance. This most impressive example of the Ranthambore Royals had seen fit to acknowledge me.

“It might be true that the feeling of getting special attention from Hamir is a figment of my own imagination, but by now, no one could dare to doubt my relationship with Hamir. My belief was unshakable and I had heard enough stories suggesting tigers may be more aware than they let on. The legendary Machli is even known to press her wounds against hot rocks whenever she got hurt to ease the pain and disinfect the wound. One can argue that this is more instinct than choice. But I have spent enough time with these cats to know better. And these revelations came to me over the course of my journey with Hamir,” Anand writes.

The journey, however, had a tragic conclusion when Hamir was declared a man eater after he had killed three forest dwellers and was confined to an enclosure within the park.

“I hate seeing this blue-eyed beauty caged like a criminal. It is the worst fate imaginable for Hamir. ‘At least he will be safe,’ I think to myself. I had such lofty dreams and hopes for him. Not that he disappointed me. Far from it. I still love him. But now, I also feel bad for him. He will never find a mate. He will never raise cubs of his own. He will never find his own home.

“He will remain an outcast, forever. My banished Prince, Hamir, remains one of the fiercest tigers among the Royals. There have been tigers, there have been man-eaters. There will continue to be. But, there can only be one blue-eyed Royal. Only one Chikoo (as one forest ranger had playfully named him). I can never see him again. Not even by accident. He has made sure of that.

“But, no matter what happens tomorrow, I will always remember him as the snarling little cub in whom I found the inspiration for a new life. He did so much for me. And while it isn’t much, this book is what I can do for him,” Anand concludes.

(Vishnu Makhijani can be reached at vishnu.makhijani@ians.in)

–IANS

vm/rs