Daneesh Majid

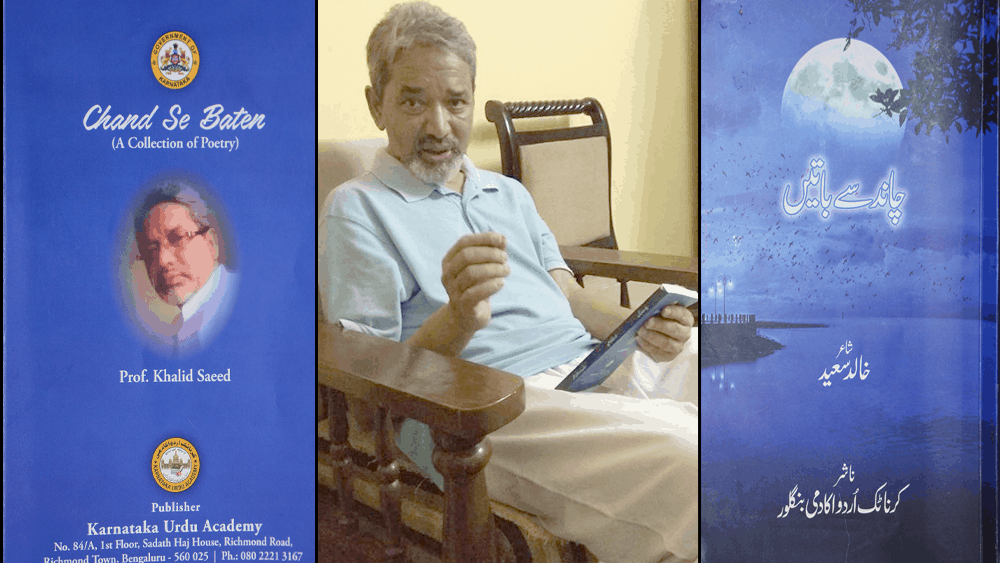

Hyderabad: Hyderabad is home to many poets from all over India. Besides, the much-feted classical poets, the city is home to an Urdu stalwart and academic, Professor Khalid Saeed.

Since his retirement from Maulana Azad National Urdu University in 2015 as the Urdu Department Head and his continuing bout with Parkinson’s disease, his latest collection of poetry Chaand Se Baatein (Conversations With the Moon) is cause for jubilation.

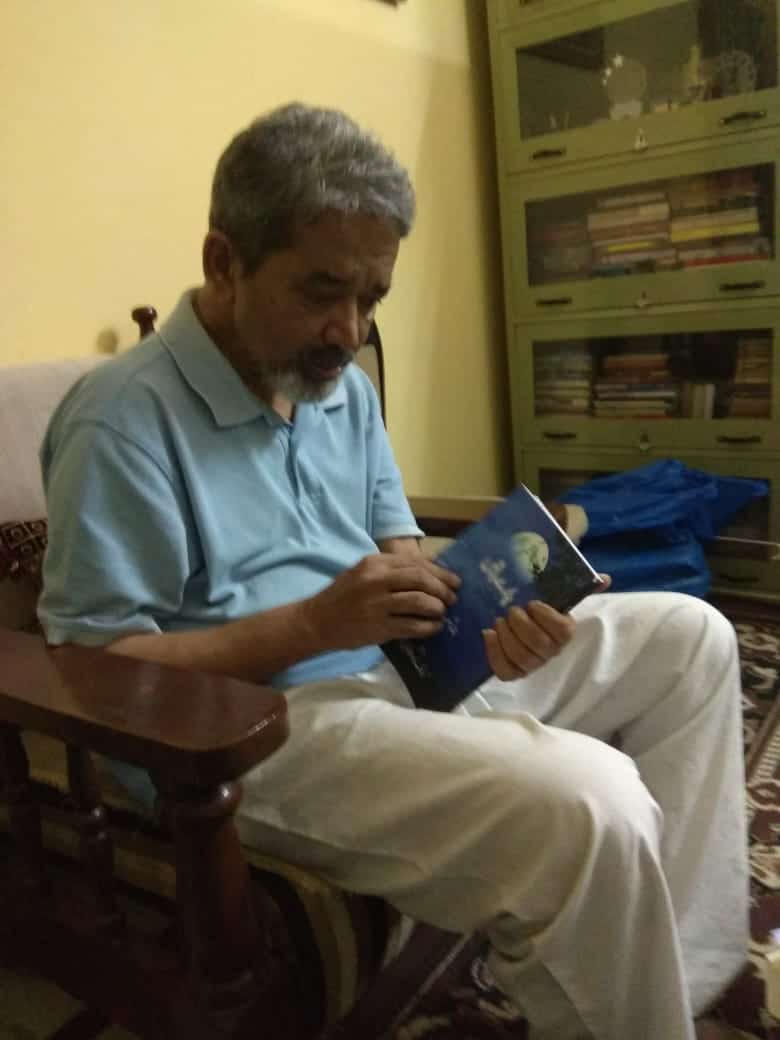

Clearly, Saeed finds solace through conversations with the moon through his poetic musings. However, when it comes to sharing his grief with people he doesn’t know how long before they turn it into gossip fodder? Hence, the former MANUU Professor is quick to deliver his eloquent lines that allude to the moon, a dear companion and symbol throughout Chaand Se Baatein. Slouched a bit upon a wooden couch at his Asif Nagar apartment, he recites,

Guzarne ke liye zeest ke andhere meiN

Tumhare chehre ki thodi si roshni bhi bohut hai

(To survive in the existence of darkness

The radiance from your face is more than enough)

These verses are complemented by some hand gestures that defy the raspy voice and feeble movements that his body has imbibed due to Parkinson’s Disease. The last two lines of his first collection of poems titled Shab: Rang-e-Numu, foreshadowed his ongoing tryst with the ailment.

Initially though, prose — not poetry — was the weapon of choice for this wordsmith who is a native of Gulbarga, Karnataka. As a nasr-nigar, (prose writer) he used to ardently consume poetry but his literary work commenced during his B.Sc days. His first short story was published in the once prominent but now defunct magazine BeesweeN Sadi.

In 1972, however, tragedy struck when his sister died. Hence, a poet was born. He recalls, “Rone ke zariye ek nazm ko janam diye, phir shayari nasar-nigari ke evaz zariya-e-izhar hua (Through my tears, I gave birth to a nazm, poetry instead of prose became my means to tell my stories).” It is this loss and the resulting desolation with the city of Gulbarga, both of which are embedded as themes within his debut collection.

The death of Saeed’s sister not only left a chasm in his life but also in his hometown as the city is a symbol of despondency throughout his debut compilation. Other than the Mirza Ghalib lines that commence Shab: Rang-e-Numu, certain fingerprints of the Delhi doyen are visible. He isn’t shy to admit that his poetry incorporates the paradoxical elements prevalent in Ghalib.

Five years prior to the Shab: Rang-e-Numu release in 1985, he began his 24-year tenure as a lecturer in Bidar. In 2004, he became an Assistant Professor in MANUU where he taught until 2015. At India’s only Urdu University, not only did he teach and simultaneously composed original verses.

Upon the suggestion of many students, he also compiled the worksheets through which he taught many non-Urdu speakers the nastaliq script into a workbook. Rather than teach the Urdu alphabet in the standard alphabetical order from Alif (ا) to Yé (ے), he taught students groups of letters separately in which the characters are categorised according to similar characteristics such as phonetics and structures.

Urdu academies of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Delhi have found this book indispensable especially since it was crafted keeping English and Devanagri script readers in mind.

This accessibility to readers and students alike can be found in his previous and latest offerings. Only minimally does one have to consult a dictionary to comprehend certain words. Besides the accessibility, poems in Chaand Se Baatein are just as personal as Shab: Rang-e-Numu. Those who are acquainted with Saeed will be able to draw parallels between his literary/academic life and symbols as well as in his compositions.

This time around, his words deal less with his personal loss and more with society, his personal trajectory after moving from Gulbarga to Hyderabad. However, the nazms which follow the ghazals deal with a variety of subjects, such as Afghanistan, Palestine and the state of Urdu at various institutions.

His ability to give life to inanimate objects, ideas, thoughts stands out throughout his original repertoire. He elaborates that shayari isn’t only about emotions. That which can be divulged in a straightforward manner can’t be deemed poetry. This is done through metaphors, similes, allegory etc.

As for personification, in Urdu, he defines it as “be-jism ko ek jism ataa karna (bestowing a body upon that which does not have a physical body).” Nowhere, is this more apparent than in this couplet:

Guftagoo kare rahe saayei se apne umr bhar

Iss tarah izzat bachayee aur yuun zinda rahein

(For ages I’ve discussed my troubles with my shadow

By doing so, I’ve saved face and stayed alive)

After all, the moon, shadows and the night are just as, if not more, trustworthy than many living beings. While reading about those confidantes and his poetic conversations with them via Chaand Se Baatein, this maqta (the last two lines of a ghazal which contain the author’s name) from his ghazal lets readers know that he hasn’t stopped wielding his deft pen.

Ahbaab meiN wo ek tha jise kehte the Khalid

Aiyaar tha, ruswa bhi tha, pyara bhi bahot tha

(Among my dear friends was one whom they called Khalid

He was sly, sullen, and lovely too)