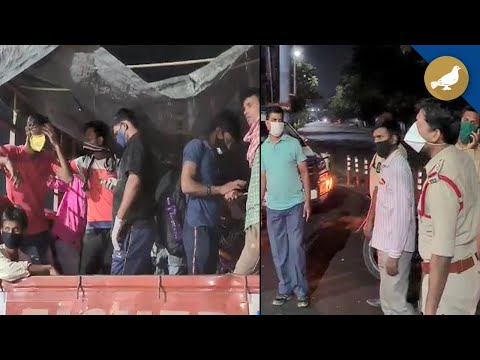

Defying the lockdown migrant workers came on the road in hundreds in Mumbai outside the Bandra railway station on Tuesday afternoon demanding that they are provided transport to back to their homes.

Most of them belong to Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal. The police taken aback at the situation and without any prior intelligence reacted by lathi charging the crowds. A few hours later migrant labourers gathered on roads in Surat- a town 290 km south of Mumbai with the very same demand. But this was the third time that crowds had collected on the roads of Surat vociferously demanding that they are provided to leave for their hometowns.

Earlier on Saturday the labourers had resorted to violence on the road due to lack of food and other facilities and a helpless director general of police had to write to the chief secretary pointing out at the worsening conditions.

Some workers cycled back home

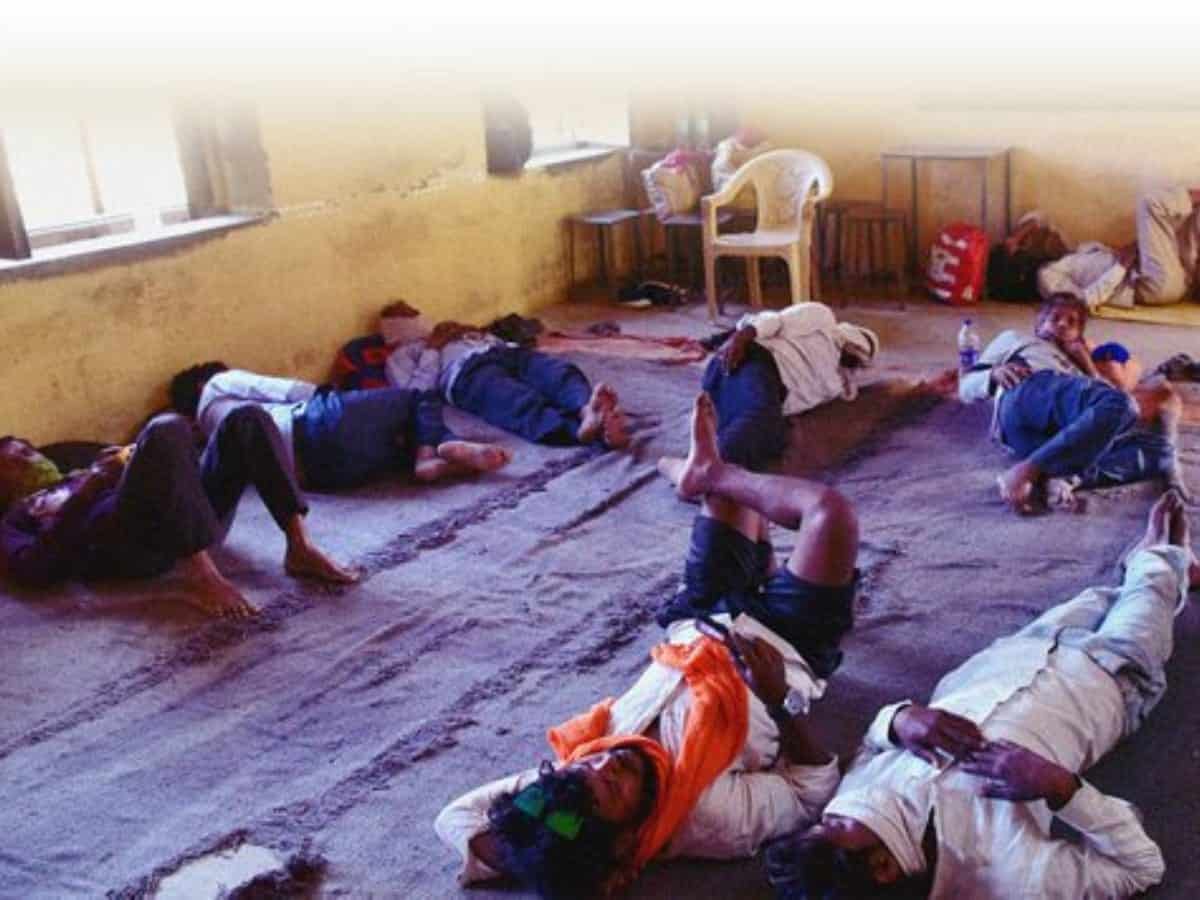

Although the middle classes and upper classes have borne the lockdown patiently, the poor are increasingly finding it difficult to bear this home imprisonment living in squalid quarters as they do. For instance, in Surat, a large part of the workers lives in ‘double shift’ in their accommodations. This means that when they go out to work, their place at home is taken by workers who have finished their shifts. Most of them are engaged in the power loom and diamond industry and with their workplaces closed now workers of two shifts are crowding their tiny quarters. Since they cannot go out and have no income they are finding it difficult to stick in their rooms, especially as the summer heat is rising. There are some instances of workers- who finding their situation unbearable- have cycled back home in Odisha which is some 1700 km away. Others have walked hundreds of kilometers in the summer heat in other states like Delhi and UP to reach home. On the way, they have had to face many adversities like paucity of food and water added to the hostility of law and orders forces as they walk across states. Some of them on reaching have faced hostile receptions and suspicions at home. Reason: they were suspected to be carrying the COVID virus.

Ready to walk in the scorching heat

In Hyderabad, a group of workers were out on the roads just after Narendra Modi spoke to the nation extending the lockdown till May 3. The workers who had probably expected that the lockdown would be lifted started walking to their homes – some 900 kilometers away in Srikakulam district – just after the PM finished his speech. However, they were intercepted by the police before they could leave the city and sent to relief centres. “You can imagine their desperation that they are ready to walk 900 km in this scorching heat,” said a police official sympathetically.

Even as the workers wend their ways back to home, the issue is also whether they will come back to work when the lockdown is lifted? Analysts feel that after taking so much troubles and tribulations to return home, many of them will be chary to come back to the cities. “At least they will not return immediately,” says Sansar Chand a mid-level businessman. Such views are echoed also by other businessmen who have got their ears to the ground. But the non -return by the workers will strike the death knell for an industry that is losing out by production (and income) fall by the prolonged closure of their units. “Organized industry may be least impacted but what happens to the informal sector. What will happen to construction activity that is heavily manpower dependent? Where will all the manpower come from,” asks Johnson, a labour contractor.

Impact on Indian economy

The Indian economy will be seriously impacted and even international agencies have now predicted that it will not grow at anything beyond 1.5 per cent in this fiscal year. But numbers and figures apart, the lockdown has put a serious question on India’s liberalization process that began in 1991. From 1950 onwards India had practised policies geared to a socialist economy with the commanding heights occupied by the public sector. Although these policies had its merits, its downsides started becoming apparent after a few decades. This included inefficiencies in the economic process and misallocation of resources. As a result, the government brought in liberalized policies since 1991 which led to higher growth. But in the name of efficiencies in the production process, unfortunately, it never focused on employment and the labour class. The result of the focus on technology and growth is now seen in striking fashion. But what use this technology and growth if it can’t bring succour to the toiling millions? The time has come to reappraise the process of liberalization and figure out how much of it is required. And to devise a process where growth is robust but the workers do not get short shrift.