As summer sets in, one of the biggest attractions that people look forward to is the mango. This heavenly fruit is India’s progeny, cultivated for thousands of years, making the country today boast of half the world’s mango supply. The love for mangoes goes back in time; it finds mention in the Vedic and Buddhist texts and the Ashokan inscriptions and the records of foreign travellers like Hiuen Tsang. It is believed that Alexander the Great carried the mango back to Macedonia from the court of Porus. Mango orchards and mango groves were planted by many rajas and sultans as part of benevolent state policies. At the same time, poets like Amir Khusrau and Mirza Ghalib make mention of the mango in their poetic compositions. More examples from Mughal histories show how distinguished a position the fruit occupied.

It is interesting to note the vivid and extraordinarily detailed picture of the mango found in Mughal testimonies. The Babur Nama considered the first autobiography in Muslim literature written by the Mughal emperor, Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur in the sixteenth century presents a thorough narrative of the mango among other fruits and flowers of Hindustan, a reference to the entire sub-continent then. Although Babur found the mango to be much glorified, in his court the fruit became popular with other members of the royalty as well as nobles.

To quote from the Babur Nama folio 282b/year 1525-6:

“When the mango is good it is really good…, few are first-rate…They are usually plucked unripe and ripened in the house. Unripe, they make excellent condiments (qatiq), are good also to be preserved in syrup. In fact, the mango is the best fruit in Hindustan. Some so praise it as to give it preference over all fruits except musk melon, but such praise outmatches it. It resembles the kardi peach. It is eaten in two ways: one is to squeeze it to a pulp, make a hole in it and suck out the juice. The other is to peel and eat it like a kardi peach. Its tree is elegantly tall, and has leaves resembling the peach trees but the trunk of the tree is ill-looking and ill-shaped.” (Babur Nama, English translation by Beveridge, II, 1921, 503-504; The Illustrated Babur Nama by Som Prakash Verma, Routledge, 2016, p.333)

Abul Fazl, the court chronicler of Emperor Akbar’s reign writes in the Ain-i-Akbari, “The mango is unrivalled in colour, smell and taste; and some of the gourmets of Iran and Turan place it above musk melons and grapes. In shape it resembles an apricot or a pear or a melon and weighs even one ser and more. There are green, yellow, red, variegated, sweet and subacid mangoes. The tree looks well especially when young; it is larger than a walnut tree, and its leaves resemble those of a willow, but are larger. The new leaves appear soon after the fall of the old ones in autumn, and look green and yellow, orange, peach coloured and bright red. The flower that opens in spring resembles that of the vine, has a good smell and looks very curious. About a month after the leaves have made their appearance, the fruit is sour and used for pickles and preserves. It improves the taste of qalyas. If a fruit gets injured whilst on the tree, its good smell will increase. Such mangoes are called koyilas. The fruit is generally taken down when unripe and kept in a particular manner. Mangoes ripened in this manner are much finer. They mostly commence to ripen during summer and are fit to be eaten during the rains; others commence in the rainy season and are ripe in the beginning of winter, the latter are called bhadiyya. Some trees bloom and yield fruit the whole year; but this is rare. Others commence to ripen, although they look unripe; they must be quickly taken down, else the sweetness would produce worms. Mangoes are to be found everywhere, in India especially in Bengal, Gujarat, Malwa, Khandesh and the Dekhan. They are rarer in the Punjab where their cultivation has however increased since his Majesty made Lahore his capital.” (Ain-i-Akbari, I, 1595, English translation by Blochmann, 1868,72; The Illustrated Babur Nama by Som Prakash Verma, Routledge, 2016, pp.333-4)

Jahangir

Emperor Jahangir in his memoirs the Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri says about the mango, “Of all fruits I am very fond of mangoes.” He further writes “Melons, mangoes and other fruits grow well in Agra and its neighbourhood.” (Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri, I, 1624, translated and edited by Rodgers and Beveridge, reproduced from a miniature in the British Museum, MS. Add. 22.282, fol.2, published by the Library of Alexandria, made in USA)

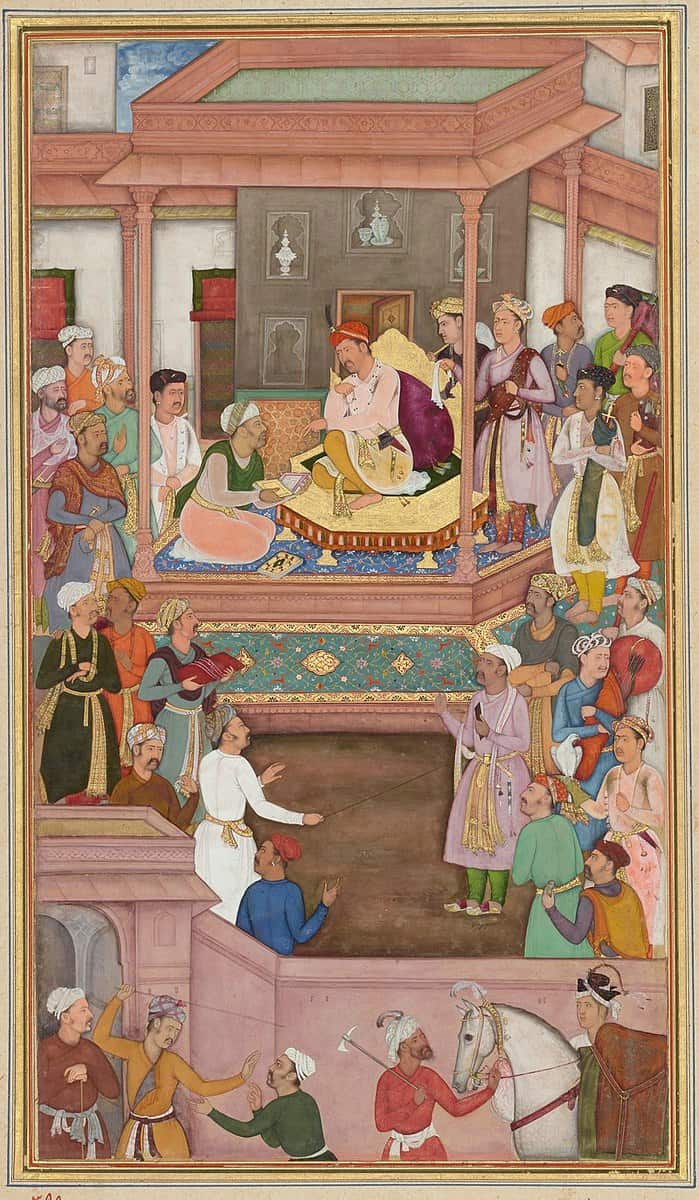

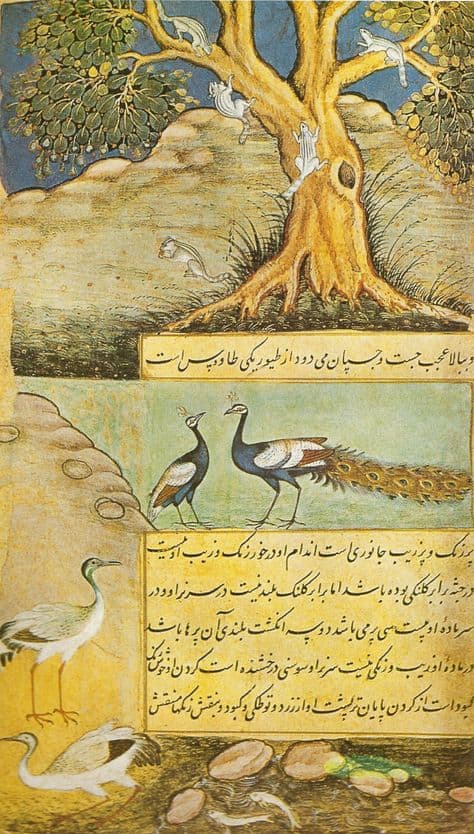

There are beautiful Mughal miniature paintings that dwell exclusively on the mango fruit. One such specimen during Babur’s time found in the Illustrated Babur Nama is titled Mango Trees and Peafowls, Agra 1590, presently housed in Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. The painting displays three lush green mango trees laden with ripe mangoes on which are perched different kinds of birds while a peacock and a peahen stroll leisurely beneath. Another miniature of Jahangir’s reign presents the emperor entertaining the King of Persia, Shah Abbas, in which on the plate kept to Jahangir’s left there are traditional Central Asian fruits such as apples, grapes, and a melon and on the plate kept to Jahangir’s right there are more exotic fruits such as oranges, lemons, pineapple, bananas, and mangoes.

These testimonies of patronage that mangoes found with the Mughals were not just for connoisseurship, mangoes were given as gifts on religious and festive occasions to stimulate diplomatic ties with associates, envoys and neighbouring kingdoms. Giving gifts, presents and honours formed an important aspect of medieval court culture. Monetary gifts, pensions, titles, robes, turbans, shawls, ornaments, jewels, arms and shields, horses and elephants as well as land grants and mango baskets in summer season were ritualistic practises which constituted a relationship between the giver and receiver and were not just simple exchange of valuable items. The number of such items and their value had a fixed status in medieval polities and symbolised an organic relationship of close associates with the ruler.

F.W. Buckler makes an interesting observation, “the Oriental despot personified four rites, which symbolized this incorporation: first, the bestowing of a khilat or robe of honour; second, the giving of nazar or offering; third, the holding of common assemblies or banquets and last, the terminology used in appointments. These rites and symbols carried the strength of binding the people to the ruler.” The humble mango basket among the other valuable gifts given and received by the Oriental despot comes within the purview of giving of nazar or offering.

While nazar typically was a term applied to gold coins in Arabic and in Persian it meant a vow, mango baskets presented as gifts to the ruler symbolized the subordinate officer’s acknowledgement that the ruler was the source of wealth and well-being. Similarly, the subordinate nobleman would also receive mango baskets from the ruler which was a token of acknowledgement to remain submissive to the ruler. The value of the mangoes being offered as nazar by and to the ruler far transcended its present market value and took on the character of incorporation and subjection.

It is not surprising that Akbar is known to have planted thousands of mango trees in Mithila, the land of Sita or Nur Jahan blended mangoes and roses into wine for her beloved husband Jahangir or Shah Jahan ensured a regular supply of mangoes from the Konkan coast to his court in Agra through a special route or Jahan Ara had on the imperial menu mango delicacies in all lavish meals that were served. Aurangzeb too made arrangements to send mangoes to Shah Abbas, the King of Persia, as diplomacy to gain some political favours and Dara Shikoh wrote in detail a treatise on mangoes namely Nuskha Dar Fanni Falahat which describes different varieties of mangoes grown in orchards, the methods of grafting and so on. This book is considered a treasure by horticulturists and formalised the practise of the Mughals patronising mango orchards and groves and led to thousands of mango varieties being planted and receiving special names which in turn led to generations of continuity of growing the fruit.

Taking a cue from the Mughals, India’s first colonial traders, the Portuguese, sent crates of Alphonso mangoes to the Muslim kingdoms in the Deccan and the Marathas on the Konkan coast as part of diplomatic protocol. The Portuguese tried to maintain the exclusivity of the Alphonso variety through control on supply but as is with all articles in demand, the Alphonso later gained patronage of the Peshwas who started mango plantations of the same variety to ensure open supply. The astute Portuguese created a lucrative opportunity for trade by carrying the different varieties of mango from India to Africa, Brazil, and other parts of the world. Thus, the mango became a global fruit in a deglobalised world.

Salma Ahmed Farooqui is Professor at H.K.Sherwani Centre for Deccan Studies, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad. She is also India Office In-charge of Association for the Study of Persianate Societies (ASPS).