After the Friday namaz had ended and the crowd filed out of a masjid in Nizamuddin West, New Delhi, I met him outside the mosque. “Apko mainstream media meiN jana chahiye (You should join the mainstream media),” the venerable Maulana told me on hearing that I was working for a tiny, now defunct magazine based a few blocks away from his Islamic Centre at Nizamuddin West.

That was the first time I met Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, Islamic scholar, spiritual leader, peace ambassador and, above all, a non-conformist. In his death India and the world have lost a strong voice of sanity, a peace ambassador, a preacher who blended Islamic teachings with Gandhian values to crusade against violence and hatred.

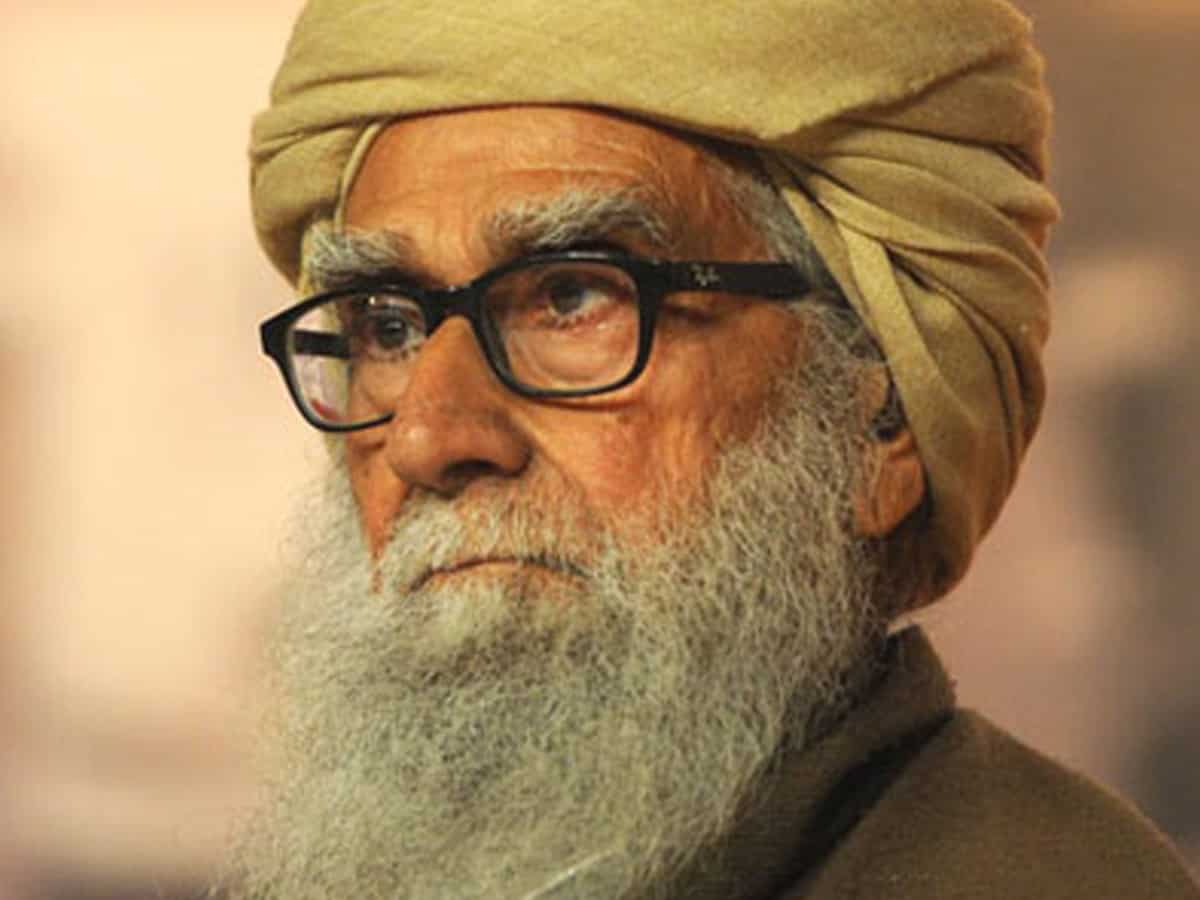

Meeting the Maulana was like getting blessed by a Sufi saint. In loose kurta-pyjama or in lungi if he was home, his piercing eyes peering through the thick glasses, the turban, the long, white beard –his persona appeared traditional in garb but he was modern in thinking. Many of the over 200 books that he penned in his eventful life of 97 years became immensely popular in the Arab world. I would have never understood the respect the Maulana commands among the Arabs had my younger brother Dr Qutbuddin who teaches Arabic at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), Delhi not explained this to me.

One cold, foggy January morning years ago, Dr Qutbuddin and I were at his weekly Sunday talk at his Nizamuddin office. Anchored by his aide and admirer Rajat Malhotra, the talk and the subsequent Q&A were streamed live on Facebook. Disciples from Delhi and Detroit, Mumbai and Miami, tuned in to hear him. That morning he chose to acknowledge the enormous ehsaan or gratitude of God. “I was a young boy in my native Azamgarh when once I took bath with cold water. I fell ill and the illness kept me down for a month,” recalled the Maulana. “But this morning, I had my bath under hot showers. My daughter helped me dry my hair with a dryer. I am so grateful to God who gave me all these facilities.” Seemingly, this was simple narration of an ordinary incident.

But then he turned ordinary incidents into extraordinary tales. It was the style of writing, infused with everyday examples, drawing on the wide reading and understanding of classical Islamic literature and modern science, that made Al-Risala, the monthly mouthpiece of his Islamic Centre, so popular. The magazine made the Maulana a household name among Urdu readers. He was a scholar who engaged with life’s issues—religious, social, ethical—in common man’s idiom. When he wrote or spoke, the Maulana didn’t pontificate. He conversed.

What I liked most about him was the positive vibes he gave. A decade or so ago some of his admirers and disciples planned his talks in Mumbai. He and his team were put up at a hotel in Jogeshwari. The Maulana fell in the bathroom and fractured an ankle. When I met him in hospital, he was as alert, agile and enthusiastic as ever. We thought his lectures would be cancelled. But next morning he surprised many of us when he was wheeling in, his fractured leg cast in plaster. He didn’t dwell on the mishap or the pain he suffered. Instead, he spoke about how to look for opportunities in adversities.

Having lost his father early, the Maulana trained himself to remain positive at all situations, good or bad. Never allowing the blizzard of criticism that some of his speeches and writings earned him, he stayed the course. He said frankly and fearlessly what he felt was good and in the interest of peace and co-existence. When the Babri Masjid—Ramjanam Bhoomi dispute caught the country in communal conflict, he came out with a formula that could have saved much time, energy and resources had the stakeholders followed it. He suggested Muslims forego their claims on the Babri Masjid site and Hindus too forget disputes in Mathura and Kashi. They rejected the Maulana’s formula as some saw it as “surrender”. That the Sangh Parivar liked the Maulana only kept many Muslims at a distance from him.

Much before Indian government scrapped Article 370 and robbed Jammu & Kashmir of it’s statehood, turning it into three Union Territories, the Maulana had earned the wrath of pro-Azadi youths of Kashmir. Once in the days of militancy in J & K, a bunch of Kashmiri boys reached the Maulana’s Delhi home. They were not militants. They were students and wanted to talk to the scholar who had taken a stand that the Kashmiris should not get misguided and abandon the struggle for a separate country. The boys kept arguing and didn’t get convinced. While they were leaving, the Maulana told them to remember his words: Kashmir’s future lies with India.

Once I took a hotelier friend to the Maulana. During the conversation the friend who runs a chain of guesthouses and hotels in Mumbai asked the Maulana about the madrassas he had attended. The Maulana had attended a madrassa in Azamgarh but he was mostly self-taught. From morning to the time he was pushed out, he would spend the day at a library, reading books. History, science, philosophy, religions, civilizations, everything and anything that he lay his hands on. His choice of eclectic reading helped him to write so cogently, lucidly and convincingly on issues that concerned us.

So, my fiend’s question about the madrassas the Maulana had attended pricked him as much as it intrigued everyone else, including one of his granddaughters, present in the room. “You are asking irrelevant questions. Do you ask your customers where did they spend the previous night?,” the Maulana said. My friend smiled and he left with the Maulana suggesting him to read some of his books.

Unlike some Islam supremacists and televangelists, Maulana Wahiduddin Khan didn’t engage in polemics. He didn’t scream from extravagantly-created podiums that “Islam is the best religion.” Neither did he raise the slogan “Islam is in danger.” His Islam was tolerant, pacifist, peace-loving, confrontation-avoiding.

So, to find solutions to many of the 20th and 21st centuries’ problems, he sought inspiration and guidance from the Treaty of Hudaibiyyah, signed in 628 between the Quraish of Makkah and the Prophet of Islam who lived in Madina in exile. This treaty though seemed humiliating and a surrender of some legitimate rights to the enemies, provided the Prophet and his followers a much-needed break from warfare. Subsequently the Prophet and his supporters returned to Makkah in a bloodless coup never heard of before. Once sworn enemies were now the Prophet’s ardent followers and bloodthirsty elements became brothers in faith.

He had trained his mind not to lament the miseries but to count the blessings divinity has endowed human life with. He established Centre for Peace and Spirituality (CPS) International to spread his message of peace and tolerance. He has left a rich legacy, not in the form of fat bank balances but of scholarship.

He was happy that I heeded the piece of advice he gave me that Friday afternoon decades ago.

Mohammed Wajihuddin, a senior journalist, is associated with The Times of India, Mumbai. This piece has been picked up from his blog