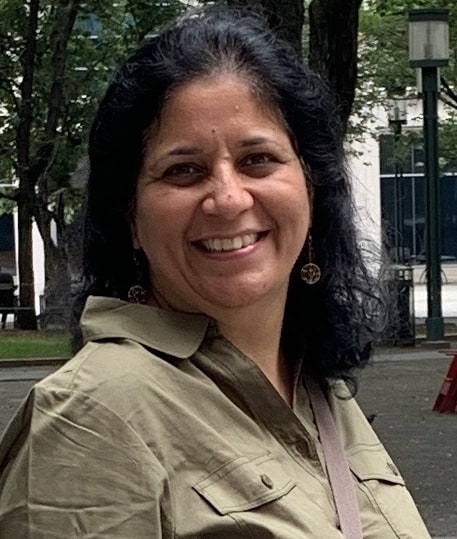

During my current research on the Brahma Kshatriyas of Hyderabad, the community members welcomed me into their homes and shared numerous stories. I have met a few 70 and 80 years old members of the community as part of an effort to build an archive on the community’s history.

The Brahma Kshatriyas settled in Hyderabad in the 1700s as part of the bureaucracy of the Asaf Jahs, the rulers of Hyderabad or the Nizam State. The most consistent storyteller was my mother, Kusum Gouri, 86. She shared with me a lot of information when I stayed with her during the summer of 2020 as the COVID-19 raged. During those four months we would finish our daily chores, a leisurely lunch and an afternoon siesta, and start our conversation or continue from where we had left earlier in the day.

One day she narrated to me about the labels of the community in which she was born. The terms “Mulki” and “Hindustani” were popularly used during regular conversations. Mulki was an ‘insider’ or a person who has been in Hyderabad for a few generations. The Hindustani, on the other hand, was a person who had migrated to Hyderabad State from the North. He was an outsider, a newcomer from another place in India to Hyderabad looking for work and to settle down here.

The origins of these labels became extremely important for finding employment. The locals would have to produce a Mulki sadaqatnama or certificate. The “Mulki Certificate” would have to be acquired from the Hyderabad State Government before seeking employment and other facilities.

It is important to note that Hyderabad State was a separate and sovereign entity; therefore, the Mulki Certificate became an important marker of identity. Mulki was the local, from the Mulk (the country), a settled person. The Mulki and Hindustani were the markers of your most prominent social identity. The controversy over Mulki and Non-Mulki became most prominent during the days of the last Nizam and after the formation of Andhra Pradesh, an amalgamation of Nizam ruled Telangana region and Andhra, the region that was under the Madras Presidency of the British India.

It was different then from the present day systems when religion, caste, and creed play an important role in establishing your identity. My mother said these factors back then were not so crucial. Maybe those identities were not yet mined for politics and Hindustani and Mulki were good minefields, enough to keep the reigns of politics in a few hands.

This explanation however is a bit too simplistic.

The Hindustani and Mulki identities were what my mother heard growing up- around the time of independence. So, this duality was a set idea by the time she grew up to be an adult.

She said that the term Hindustani was used as an insult to address the new migrant that came to Hyderabad in search of jobs and who did not possess a jagir, or an ancestral property. The Hindustani arrived in Hyderabad with bare minimum belongings and according to my mother, it is said that they arrived with a “thali (a plate) and lota (a globular water container)”. As opposed to Hindustani, the Mulki or the Hyderabadi was a local person who is well settled and perhaps had landed property given by the Nizam. He was well placed in the feudal ways of life. (However, not all Mulkis were jagirdars).

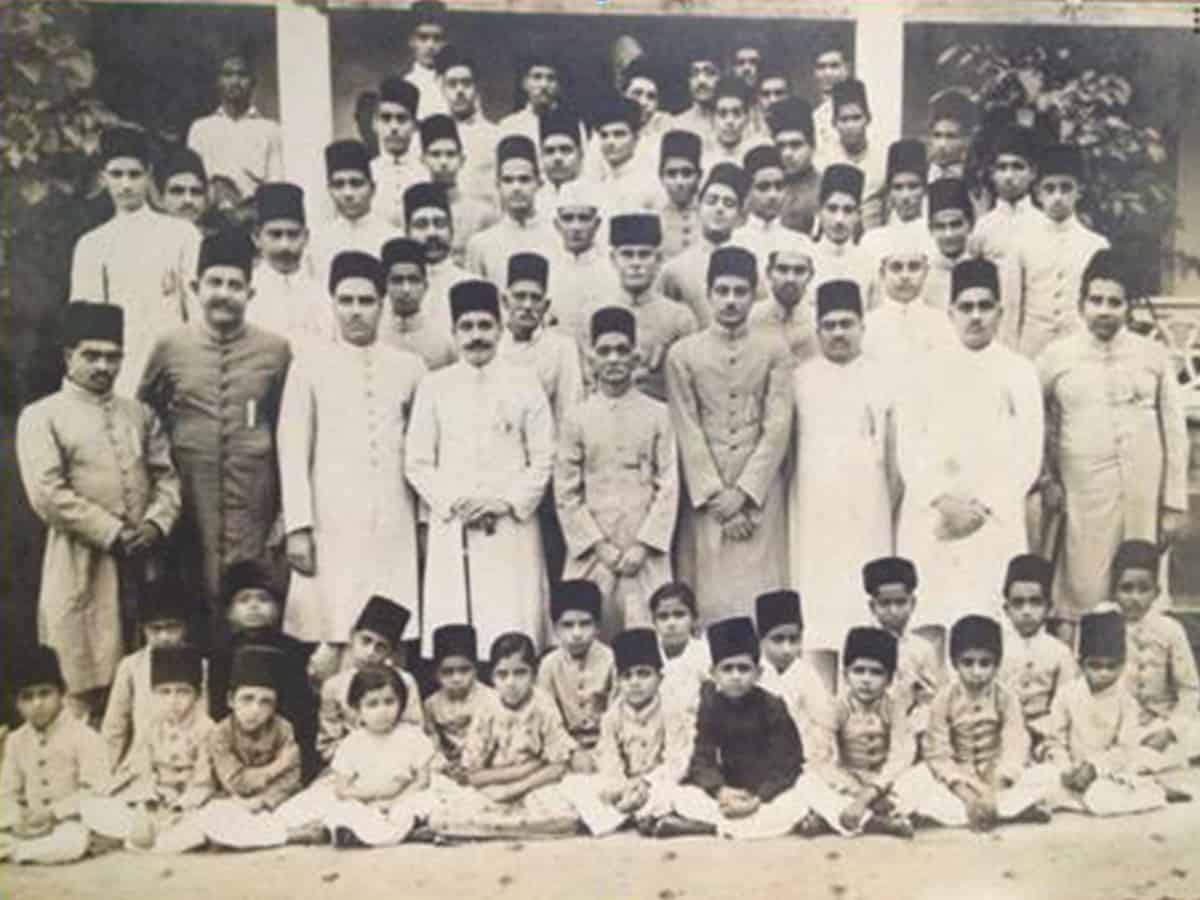

My mother recalled that Jagat Narayan, Shiv Govind Pershad, my paternal grandfather, and his brother Bal Govind Pershad, came from Lucknow which is today the capital of Uttar Pradesh, the biggest province in India. Also, Jagannath Das Mahendra, who was employed in the Police headquarters along with Ganesh Narayan who was from Gujrat.

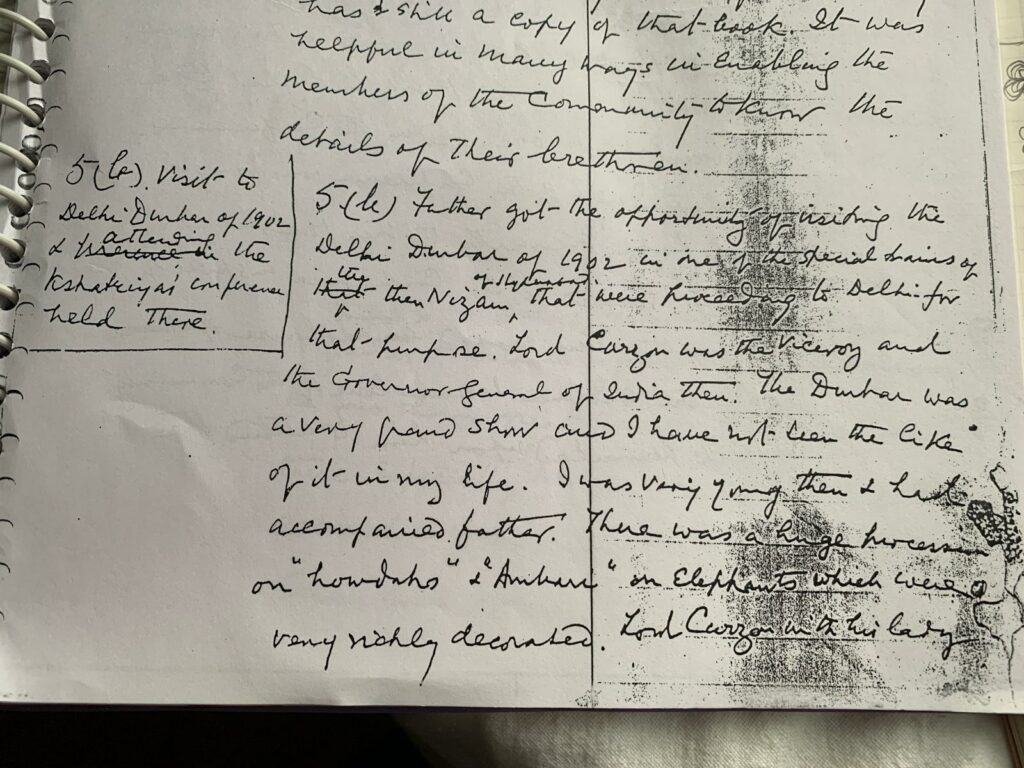

Dr. Girish Narayan, the great-grandson of Jagat Narayan spoke in detail about this when I met him in 2019 and then more recently when I met to him about his grandfather Ganesh Narayan’s meticulously kept diary. This diary begins in the 1950s and starts with an account of his childhood spent with his father described in minute detail. Some of the interesting anecdotes in the diary include a visit to the Delhi Durbar in 1902 when Lord Curzon was the viceroy and the Governor General of India. It had involved a grand show. The Nizam Mahbub Ali Khan government had organised a special train for this purpose. There was also mention of the founding of the school in Charminar area by the community and fighting social evils such as child marriage.

Jagat Narayan is one of the important figures in the history of this community. He was the first to complete B.A. and had a poem written about him for such an achievement. He was also one of the few members who aspired to document the community’s history. At the same time, he was one of the founders of the community’s Mufeed Ul Anam School. He later became instrumental in initiating various reforms for the benefit of the community. My conversation with his grandson Sukh Deo Narayan, 95, yielded interesting snippets from Jagat Narayan’s life. Jagat Narayan was a social reformer and worked hard to abolish alcoholism in the community. He was humiliated for this initiative. He was the outsider, far enough out on the margins to be critical of the community’s problems. As a show of opposition to his critique, it is said that he was adorned with a garland of shoes which he accepted with open arms. He was unfazed by the insults for the cause he believed in. Is it easier to critique from the outside than to do so from inside a community? What enables this process? Is it because a certain distance is available to provide a lens and also a perspective? And what value does this story of censure bring to our minds?

While Hyderabad has been a city of migrants, the Hindustanis were the poor lot, the ones that had to make a living or work to survive. The Mulkis, or jagirdars, lived a life of “thaat”, of splendor and excesses and did not work. Visiting the house of a Hindustani or being socially close to them was considered anathema. It was looked down upon because they were the newcomers to the city. You socialized with them but they were not invited to the important gatherings and kept at arm’s length. “Roti aur beti bahot ahem hai beta,” said my mother. It meant you have to be careful where you get your daughter married and who you sit down with to eat — rules that form the structure of endogamy. However, this changed within a span of a generation and the Hindustani went on to be a part of the new middle class, the educated lot that was instrumental in much of national development.

I was born and raised in Hyderabad speaking not only Dakhani, but also fluent Telugu. However, growing up, I found that I was not a Telugu like my friends in Women’s College, Koti, nor was I a local Muslim in Stanley Girls High School, Chapel Road. I did not ever go to my “native place” when most of my friends would go away during the summer holidays.

I saw myself as someone on the margins of conversations and to the dominant culture since an early age. Being marginalized not in the conventional economic sense but culturally was something I have been used to for most of my life.

I moved to the United States in the year 2000 and I was again confronted with questions of identity in a new way. From other Indians, the questions were, am I from the North or the South of India? Was I a Telugu or was I a Punjabi? And if you know me, you know I grew up without a last name; I was always Hema Malini or just Malini. Waghray was something that was added to my paperwork because the USCIS (US Citizenship and Immigration Services) had a field that was otherwise filled with LNU – “last name unknown” for Hema Malini. So, the Marathi sounding last name that got added for my citizenship in the US further confused others in this rigid framework of identity. (And here’s another story for another time–my mother, my mother-in-law, my aunt-in-law, some of the important matriarchs I know, do not own last names or use them. Although these days, a wedding invitation will bundle them up with their husbands, a brother and now a son).

I recall wondering about these questions and thinking, “Wow, I might actually be a Punjabi because my family name from my dad’s side, ‘maiden name’ being Gayhee or Ghai.” That said, the one thing that definitely sat well with me, as part of my identity, was being a Hyderabadi, belonging to the geography and the culture of Hyderabad. So, when I was asked who I was and where I was from, a typical profiling question from other Indians in the US (including me), I would say Hyderabadi and I taught my kids to say that as well. My kids, nieces, and nephews speak the Dakhani language, which is a distinct dialect of Hindi/Urdu from the Deccan region. Before I left Hyderabad, I did not relate so much to the regional hierarchies of North versus South India but after moving to the US, I became aware of a new identity being cast on me as a Punjabi with some hesitation. Hyderabadi is the closest identity I take on and it persists because so much of what I do and who I am on an everyday basis is a part of the Hyderabadi culture.

This attitude of otherness towards outsiders was a common practice even among the Muslims of Hyderabad back in the day. This essay started off after a conversation with my mother. But at a later stage I spoke with Mr. Mir Ayoob Ali Khan of siasat.com from Hyderabad. He spoke about this, as being a common practice among the Muslims of Hyderabad. He said that Muslim migrants from outside Hyderabad were called Hindustani and locals were called Hyderabadi or Mulki. Although we have evolved as a society, over time we have found new politics and have made religion and caste into minefields.

How did this politically accented polarization play out in everyday interactions? This process of othering is available in many forms but always seems to be present in society. A very humane and loving person can nurture the feeling of otherness in someone quite easily. It’s insaani fitrat, human nature, too. Today’s saturated media and social media culture enable it down to our minute moments, through WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook and more.

Marginality in India is about caste politics but also political parties as well as class. It is about your religion and your geography. Politics pushes and enables these labels and identities and will always find ways to divide people. As Teju Cole says: “The priorities of the State are inimical to the priorities of justice and ethics; States are good at dehumanizing.” But asking these questions is key to unraveling that which bothers us. It is by way of these conversations that one is able to question and talk back to the past in some way. It is these answers that will allow us to zig-zag out of this maze; to find out how we got to where we have arrived.

If the Hindustani arrived with the thali and lota, they probably arrived with fewer shackles of tradition that come with property and ownership of things, of money and status. Jagat Narayan and later Ganesh Narayan despite being the outsiders in the community were among those who were instrumental in encouraging both men and women to educate themselves. My mother and many other men and women of her generation benefitted not only from this education but also from the mentorship of this Hindustani, the outsider.

Hema Malini Waghray is an American research scholar with her roots in Hyderabad.