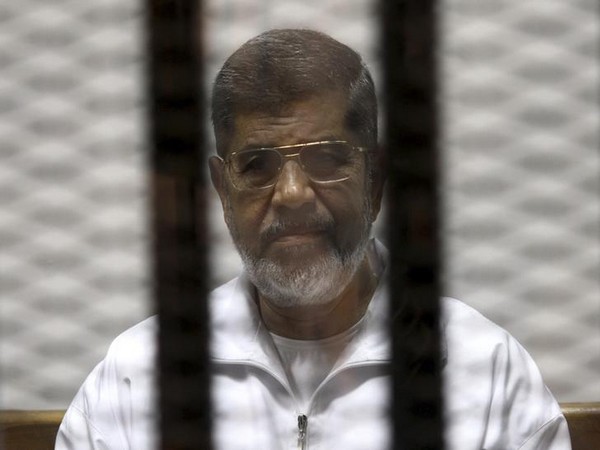

Mr. Morsi, 67, won Egypt’s first free presidential election in 2012 as a senior leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, but was removed from power a year later in a military takeover. Since then he faced a raft of charges including terrorism, spying and breaking out of prison in trials that human rights groups say are deeply flawed, The New York Times reported.

The first freely elected president in Arab history to occupy that role, Mr. Morsi was elected on June 17, 2012, seven years to the day before he died. His election was the apex of the Arab Spring uprising, and a high point for the Muslim Brotherhood, a 91-year-old movement founded in Egypt for the implementation of Islamic ideology and whose influence extends across the Arab world.

For many Egyptians, Mr. Morsi’s election was their greatest hope for a definitive break with the country’s long history of autocracy after decades of harsh and corrupt rule under President Hosni Mubarak, who was ousted in the 2011 uprising.

Some Egyptians worried that he might impose strict Islamic moral codes, while critics in Washington and around the region raised alarms that he might even seek to establish a form of theocratic rule.

Mr. Morsi surprised many by seeking cordial relations with the United States and maintaining diplomatic ties with Israel. He developed a warm working relationship with President Barack Obama, and the two men worked together to help stop a bout of fighting between Israel and the Palestinian militant group Hamas in the fall of 2012.

But at home, Mr. Morsi’s rule was troubled from the start. He at one point issued a decree that critics said put him above the rule of law. Supporters said the decree was part of his efforts to grapple with a hostile security establishment that was actively maneuvering to undermine his authority.

In the early summer of 2013, giant protests against Mr. Morsi filled Tahrir Square, the crucible of the 2011 uprising, providing the military with an excuse to oust him.

His defense minister, Gen. Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, seized power on July 3, 2013. Six weeks later, Egyptian security forces shot dead at least 817 protesters, mostly from the Muslim Brotherhood, in what human rights groups called the largest mass shooting of demonstrators in recent history.

Mr. el-Sisi was elected president in 2014 and still rules the country with an iron grip, with Egypt’s democratic hopes largely extinguished.

A referendum in April to allow Mr. el-Sisi to remain in power until 2030 was passed overwhelmingly in a flawed vote that allowed no opposition voices.

Egyptian television channels, which are tightly controlled by the security services, offered equivocal coverage of Mr. Morsi’s death. Some did not interrupt their usual programming to report the demise of a former president.

Other channels aired footage portraying the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization. “Lies are an integral part of the Muslim Brotherhood,” said a voice on CBC Extra, a private station, after a segment that showed Islamic State fighters threatening to attack Egyptian soldiers.

There was no immediate comment from President el-Sisi’s office.

The handful of people in Egypt willing to speak sympathetically about Mr. Morsi avoided his politics and focused on the conditions of his detention. “He was a victim of brutal prison conditions,” Gamal Eid, a lawyer and human rights advocate, said by phone from Cairo.

Mr. Morsi had been charged with various crimes in politicized trials that have dragged through Egypt’s slow-moving courts. In 2016 his son, Abdullah, told The New York Times that the family feared that the former president might fall into a diabetic coma.

Unlike most prisoners in Egyptian prisons, Mr. Morsi was barred from receiving deliveries of food and medicine from his family, said Ms. Whitson of Human Rights Watch. In addition to being held in solitary confinement, he was denied access to the news media, letters or other communication with the outside world. His wife and other family members were allowed visit just three times in the six years he was imprisoned.

In March of last year, a panel of British politicians and lawyers reviewing his treatment concluded that Mr. Morsi had received “inadequate medical care, particularly inadequate management of his diabetes and inadequate management of his liver disease.”

Failure to address his care, the group warned, could put Mr. Morsi’s life in danger. In a statement on Monday, Crispin Blunt, a member of Parliament who led the panel, said: “Sadly, we have been proved right.”

Mr. Sadek, the Egyptian prosecutor, ordered an immediate investigation into the cause of death. In a statement, he said he would seek Mr. Morsi’s medical file and order a committee to prepare a report on the cause of death.

Investigators will use surveillance footage from the courtroom and question witnesses who were with Mr. Morsi when he died, the statement said.

After overthrowing Mr. Morsi, Mr. el-Sisi sought to banish the Muslim Brotherhood, calling it a terrorist group and sparing little effort to discredit it among the Egyptian public. Most Brotherhood leaders are in jail or exile, and thousands of its members languish in Egypt’s crowded prisons.