Karni Sena’s protest against film Padmaavat has turned violent. They are targeting from public property to innocent school children. The situation is not only unfortunate but ridiculous too, as Rani Padmini is not mentioned in any Rajput or Sultanate annals, and there’s absolutely no historical evidence that she existed. The saga of Alauddin Khilji attacking Chittorgarh smitten by the beauty of Maharani Padmini is the creative production of Sufi poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi.

This is historical fact that Rajput ruled Chittoor till 1303 when Alauddin Khilji had captivated and also from 1336 to 1557. But Rajput history has no mention of Padmini nor any other queen or Maharani. Rajput historian Gaurishankar Hirachand Ojha in his book ‘Udaipur Rajya Ka Itihas’ in 1936 has written that mention of Chittoor’s Raja Rawal Ratan Singh was first found on a pillar erected in the Devi Mandir in Dareeba in Rajsamand. The pillar was discovered by Indian archaeological department in 1930. The date on the pillar is 1301. But there is no mention of Maharani or rani.

On the other hand, the detailed narration of war between Alauddin Khilji and Raja Rawal Ratan Singh is found in Amir Khusro’s ‘Khazain-ul-Futooh’. Amir Khusro, the court poet of Khilji, who accompanied him during the Chittoor attack did not write about Padmini nor allude any episode to her in his book ‘Twarikh-e-Allai’. He has never in any of his works mentioned if Khilji attacked Chittoor for Padmini. “Chittoor was attacked by Khilji for its forest and mineral wealth and as part of his expansionist agenda,” said Lokendra Singh Chundawat, history department head at the local PG College.

There is also no mention of ‘Jauhar’ by Rajput women in the Fort. Naturally when there was no Rani named Padmini then it is out of place that she would have no mass sati.

Dr. A K Mittal, professor of Gorakhpur University in his book ‘Bharat Ka Rajnitik Evam Sanskritik Itihas’ has clearly mentioned that the records of ‘Khazain-ul-Futooh’ give evidence that Alauddin had not made an attack on Chittoor for any ‘Padmini’.

Now the question arises why Malik Mohammed Jayasi wrote a story related to Alauddin Khilji. It may be because such romantic stories were very popular those days. It is also possible that Jayasi might have consciously or unconsciously confounded Ala al-din Khilji with Ghiyath al-din Khilji of Malwa (1469–1500) who had a roving eye and is reported to have undertaken the quest of Padmini, not a particular Rajput princess, but the ideal type of woman according to Hindu erotology. Ghiyath al-din Khilji, according to a Hindu inscription in the Udaipur area, was defeated in battle in 1488 by a Rajput chieftain Badal-Gora.

The ruse of warriors entering an enemy fort in women’s palanquins, had also some historical basis as it was used by Sher Shah to capture the fort of Rohtas. In 1531, nine years before the composition of Padmaavat, a case of mass sati by Rajput noblewomen had occurred in a Rajput fort sacked by Sultan Bahadur of Gujarat to avenge the dishonour of two hundred and fifty Muslim women held captive in that fort.

It, therefore, seems that Jayasi incorporated several near-contemporary historical or quasi-historical episodes in the original legend. Jayasi himself confesses at the end: ‘I have made up the story and related it.’

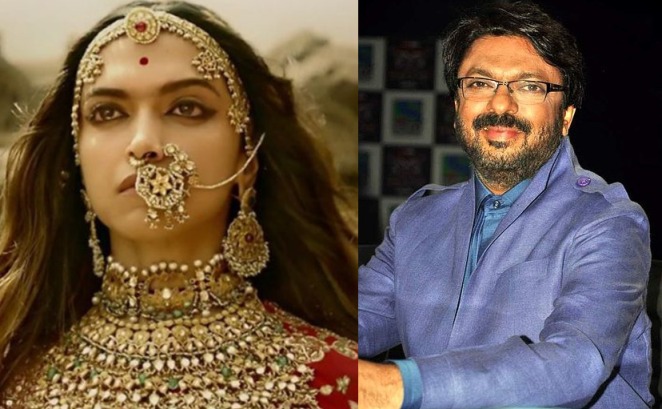

Notwithstanding whether Padmini’s character is real or fictional, the strong protest against Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s film is meaningless. As this is not the first time the story has aired on screen. The story was also depicted in 1988 in the 26th episode of ‘Bharat eik khoj’ aired on Doordarshan.

Unfortunately, the controversy over film Padmaavat has diverted people’s attention from other political and burning issues, fulfilling the aim of ruling political party.