Washington: Researchers have figured out a new method to bypass the blood-brain barrier in situations where it begins to play a counterproductive role by expelling the immune system cell through its drainage system.

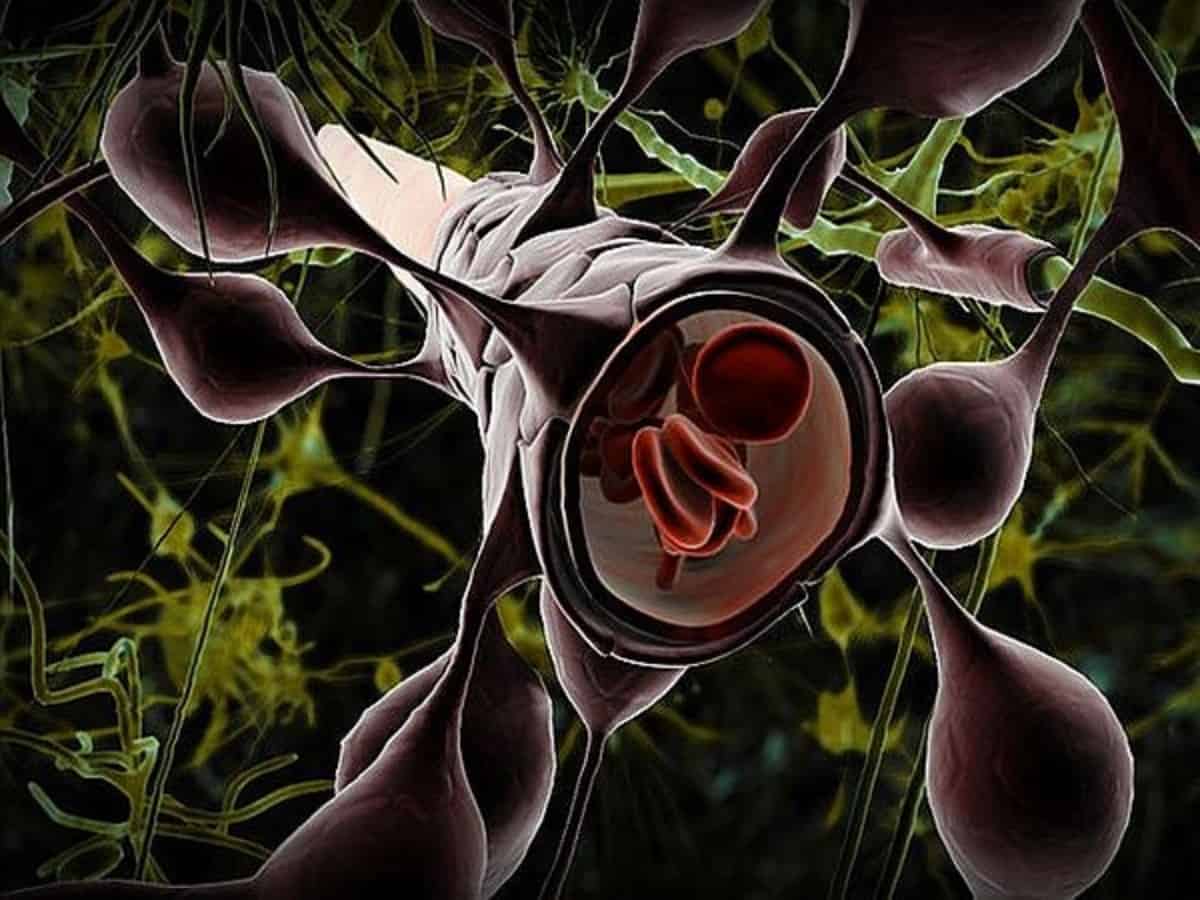

The brain is a sort of fortress, equipped with the blood-brain barrier that is designed to keep out dangerous pathogens. However, such protection comes at a cost: These barriers interfere with the immune system when faced with dire threats such as glioblastoma, a deadly brain tumor for which there are few effective treatments.

“People had thought there was very little the immune system could do to combat brain tumors,” said senior corresponding author Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of Immunobiology and molecular, cellular, and developmental biology. “There has been no way for glioblastoma patients to benefit from immunotherapy.”

While the brain itself has no direct way for the disposal of cellular waste, tiny vessels lining the interior of the skull collect tissue waste and dispose of it through the body’s lymphatic system, which filters toxins and waste from the body. It is this disposal system that the Yale researchers exploited in the new study that got recently published in the journal Nature.

These vessels form shortly after birth, spurred in part by the gene known as vascular endothelial growth factor C, or VEGF-C.

Yale’s Jean-Leon Thomas, associate professor of neurology at Yale and senior co-corresponding author of the paper, wondered whether VEGF-C might increase immune response if lymphatic drainage was increased.

Lead author Eric Song, a student working in Iwasaki’s lab, wanted to see if VEGF-C could specifically be used to increase the immune system’s surveillance of glioblastoma tumors. Together, the team investigated whether introducing VEGF-C through this drainage system would specifically target brain tumors.

The team introduced VEGF C into the cerebrospinal fluid of mice with glioblastoma and observed an increased level of T cell response to tumors in the brain. When combined with immune system checkpoint inhibitors commonly used in immunotherapy, the VEGF-C treatment significantly extended the survival of the mice. In other words, the introduction of VEGF-C, in conjunction with cancer immunotherapy drugs, was apparently sufficient to target brain tumors.

“These results are remarkable,” Iwasaki said. “We would like to bring this treatment to glioblastoma patients. The prognosis with current therapies of surgery and chemotherapy is still so bleak.”