Sindh’s saints and savants are dust. Even its living are slowly dying. The Endowment Fund Trust in Karachi however ensures that Sindhi culture survives.

The EFT ignored warnings about COVID-19 and Omicron by holding a public launch on 23 January of I Saw Myself, a book on Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai. The book was co-authored by two Indians: Shabnam Virmani and Vipul Rikhi. As Indian publications are deemed seditious by their very origin, it cannot cross the border. EFT reprinted it in Pakistan.

The book launch reunited on one screen Indians and Pakistanis to honour an 18th century poet who wrote of borderless love with an unquenchable, unrequited passion.

Shah Abdul Latif (1689-1752) and his spiritual guides Rumi and Kabir did not belong to one area or to one time. They were of their time, for their time, and for ours.

Translators allow us to savour their poetry, to enjoy what the authors describe as ‘the orality’ – ‘the feeling behind the words’, for Shah Latif’s famous Risalo is ‘a collection not so much of poetry meant for reading, as much as it is a collection of musical verses meant for singing [.] The thirty Surs into which the Risalo is divided are chapters clustering poetry around a specific theme, but more literally they are ‘musical modes’ based on specific Indian ragas, intended for a musical experience.’ [Miniature painters picturised them as a Ragamala of 36 ragas and raginis.]

‘Shah Latif was clearly among those Sufis who recognize the power of sound in spiritual practice.’ Or what the aesthete Mughal prince Dara Shikoh called the ‘infinite and absolute sound’ – the Voice of Silence.

Shah Abdul Latif’s Risalo is divided into dastaans, consisting of beyts. ‘Each singer picks up the thread of the previous singer’s beyt, and sings another evoking the same theme, creating a complex musical and poetic ambience.’

Akin to the dastaan tradition of ‘orality’ such as the Tilism-e-Hoshruba, it relied upon the human voice to convey imagery, to conjure imaginary heroes and heroines, characters and dramatic action that unfolded at the speed of speech. Shah Abdul Latif’s poetry travels at the speed of sound – the sound of a human heartbeat, the sound of breathless love, the sound of a soul’s silence.

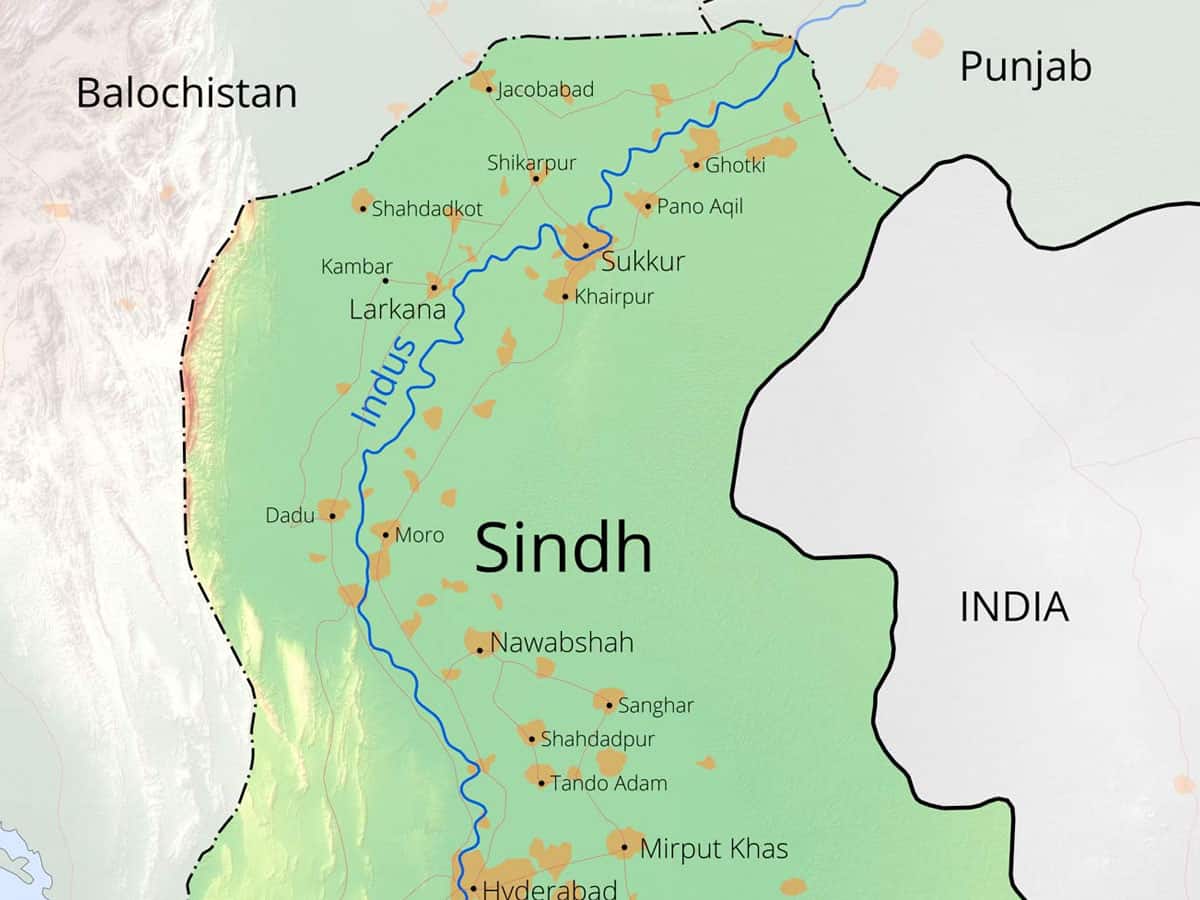

Shah Abdul Latif was born in 1689 in the modest village of Hala Haveli. He fell in love with a girl from Kotri. His father objected. Shah Latif reacted by travelling aimlessly across Sindh. On his father’s death, he married his beloved, only to lose her a few years later. Thereafter, poetry became Shah Latif’s emotional companion.

’If music be the food of love, play on,’ says Count Orsino in Shakespeare’s play Twelfth Night. Like the Count, Shah Abdul Latif was more in love with the idea of being in love than with love itself. Similarly, Shah Latif’s love is not for one woman but for the female ideal. His Risalo contains a number of heroines – Sohini, Sassi, Marvi, Moomal, Leela and Noori. Their adventures are dramatic at one level, allegorical at another.

We know that the heroines represent mankind and the masculine beloved is a symbol for God. Sohini is determined to cross the river to meet her beloved, even at the risk of drowning. But at the highest level of spiritual ecstasy, Shah Latif tells us, is not to be united with one’s lover but to lose oneself, not to reach the other bank but ‘to merge in the swirling waters of the river itself.’ A modern Punjabi poet Munir Niazi expressed it thus: Kuch shehr dey log vi zalim san; Kuch sanoon maran da shauq vi see. (The townsfolk were cruel; but I myself courted death.)

Shah Latif’s belief in the release offered by death pervades every poem. His princess Shireen implores to be entombed with her soulmate – a dishevelled fakir. She recites: ‘In all moments we carry a spade and a string/ to dig and measure out our graves.’

Surprisingly, the Indian authors do not mention H. T. Sorley’s seminal work Shah Abdul Latif of Bhit: His poetry, life and times, published in 1940 in Mumbai, and reprinted here in 1966 – an earlier instance of literary migration.

Sorley published an abridgment known as the Munthakab, collected by Kazi Ahmad Shah. containing the most popular of Shah Abdul Latif’s verses. Sorley admires Shah Abdul Latif as ‘the first great exponent of the imaginative use of the Sindhi language’. One understands why after reading Shah Sain’s plaint: ‘Even if you lay beyond sunrise and sunset,/ I would still walk to you on the feet of my eyes.’

EFT’s reprint of I Saw Myself is more than medicine for our minds. It nourishes our souls — a sort of Poetry sans Frontières.

Fakir S Aijazuddin is a noted thinker and columnist of Pakistan