Rama Sundari

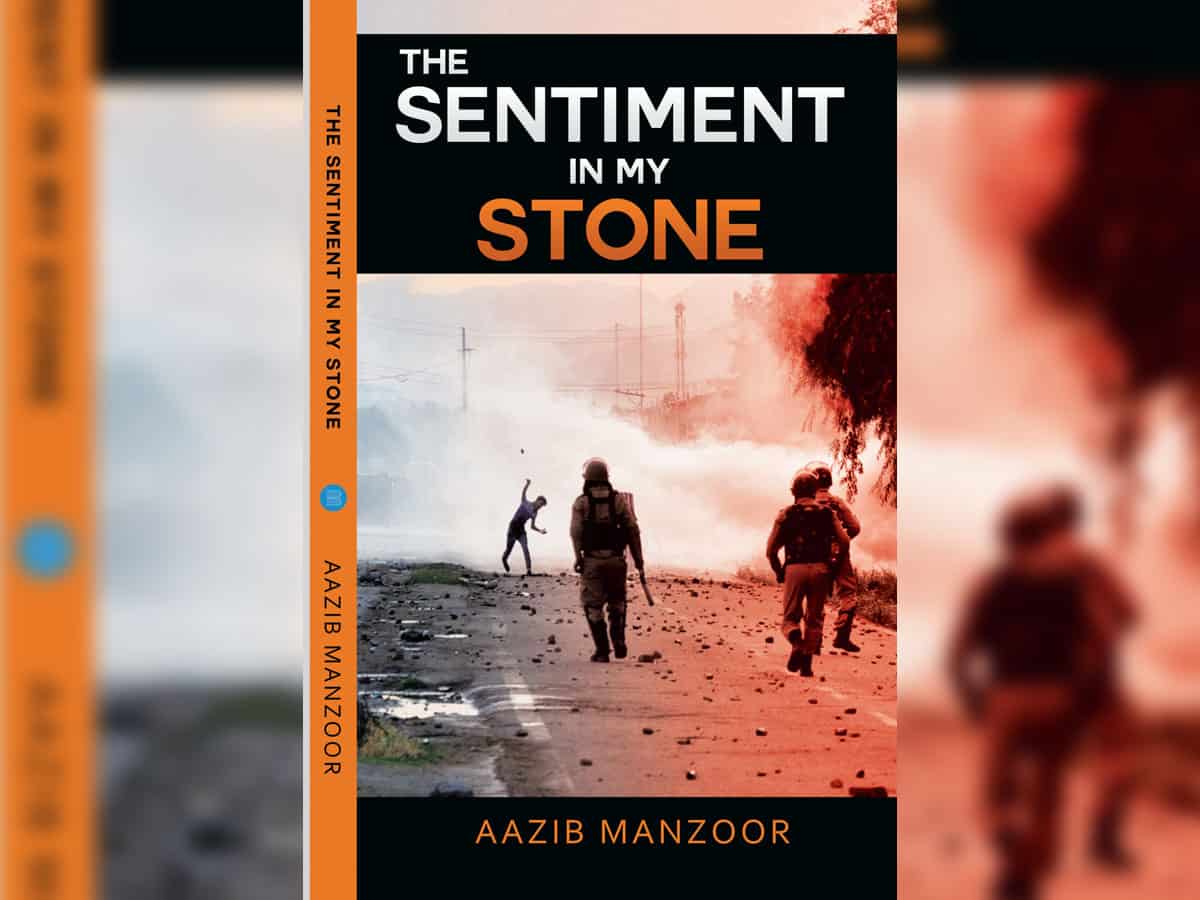

Coming of age in a territory under military siege without detriment is the biggest struggle encountered by youth of Kashmir. This battle with the spread of mighty force is not confined to the individual but the entire family, relatives, and Kashmir society. The Sentiment in My Stone is a book that brings us a collection of experiences of many Kashmiris, though it appears like the author Aazib Manzoor’s memoir.

The author starts developing the narrative from a patriarchal family set-up – omnipresent in every society. Aazib starts knitting the story hinting that Kashmir is no exception to it. But the book explains that intensity of tyranny by the largest military base of the world in Kashmir extends to such a degree that it transcends all previously existing evils of that society. Here a possessive father and a dominant husband become helpless when he must face the additional horror in the name of the State. He who inters the lifeless bodies of their sons in graves with his shaky hands.

The author tells us how the term non-violence becomes irrelevant to a populace subjugated by an army, why the ground realities compel an energetic college youth to pick up arms, and what it means to a school-going boy to witness the violence perpetrated by army personnel on his loving brother. The argument put forth by the author resonates with the readers.

The protagonist’s adolescent love runs parallel to the main storyline that frames the reasons for his tender mindset. The author brilliantly juxtaposes a backbencher’s obsessions –fantasizing about his crush, struggling to make friendships, his introverted comportment, his longing for solitude whenever he has a confrontation with the cultured society around him.

The book poignantly explains that in a land where even a kid knows the meaning of Azaadi, when in speaking it and what wonders it had wrought –there is an overwhelming consent for rebellion. Rebellion he says, under duress become a synonym for a civilization that was under despotism for centuries. A conversation in the story when army personnel beat the protagonist’s brother lays this bare very plainly. Everyone who goes to see him narrates their own horror stories – making it clear to the reader that violence is part of their daily life. The harsh reality is that one need not commit an offence to be punished there. The author is charitable enough to listen to the views of ‘others’ in this deeply troubled world such as an Indian Muslim military person, or a mainstream politician’s brother.

The compelling reasons behind the rage that manifests as protests, stone-pelting and other kinds of dissent, including taking up of arms, are revealed as the cumulative impact of many factors such as the killings of individuals for no reason, rapes, beatings, and humiliation. In a State where no man can live with self-respect, no father can protect his boys, and no mother can save her children under her warm embrace –the option they are left with is rebellion.

Defence – the other name of resistance – is not a simple word that implies protecting oneself from an attack. The author shows us that ‘It is a continuous process until the powerful drops weapons at the feet of the powerless.’ Living under the inescapable dark shadow of violence triggers every soul to long for an experience of protest. One cannot call it just ‘anger’ as clarified by the author in recounting a protest rally – ‘it is a river of abomination in every scream, in every cry, in every slogan, in every step, in every ounce of energy utilized.’

As experienced by the protagonist, stone-pelting is an act when ‘Fire, flame, wrath, destruction, blood and flesh; everything assimilated in the hands to drain the pretty and petty fear out of my body’. A way of conveying disgust to occupation, an internationalised self-esteem – stone-pelting cannot currently be judged as an act just of violence, argues the book. When the not so pretty resistance turns out to be a necessity for a society, it certainly becomes a part of it. What rationales could lead a common lad to choose the battlefield as his ‘meadow of desires?’ How come it is more likely that instead of his legs, his heart and soul take him to ‘red road?’ When do we realize that this entire act of revolt is not confined to individuals, but that it is a sentiment that has engulfed the community as a whole – are these questions worth being answered at once?

This book deserves to be placed among the select set of best books to understand the Kashmir conflict.

Rama Sundari is editorial board member of Matruka magazine and a socio political activist based in Guntur, Andhra Pradesh