By Soutik Biswas

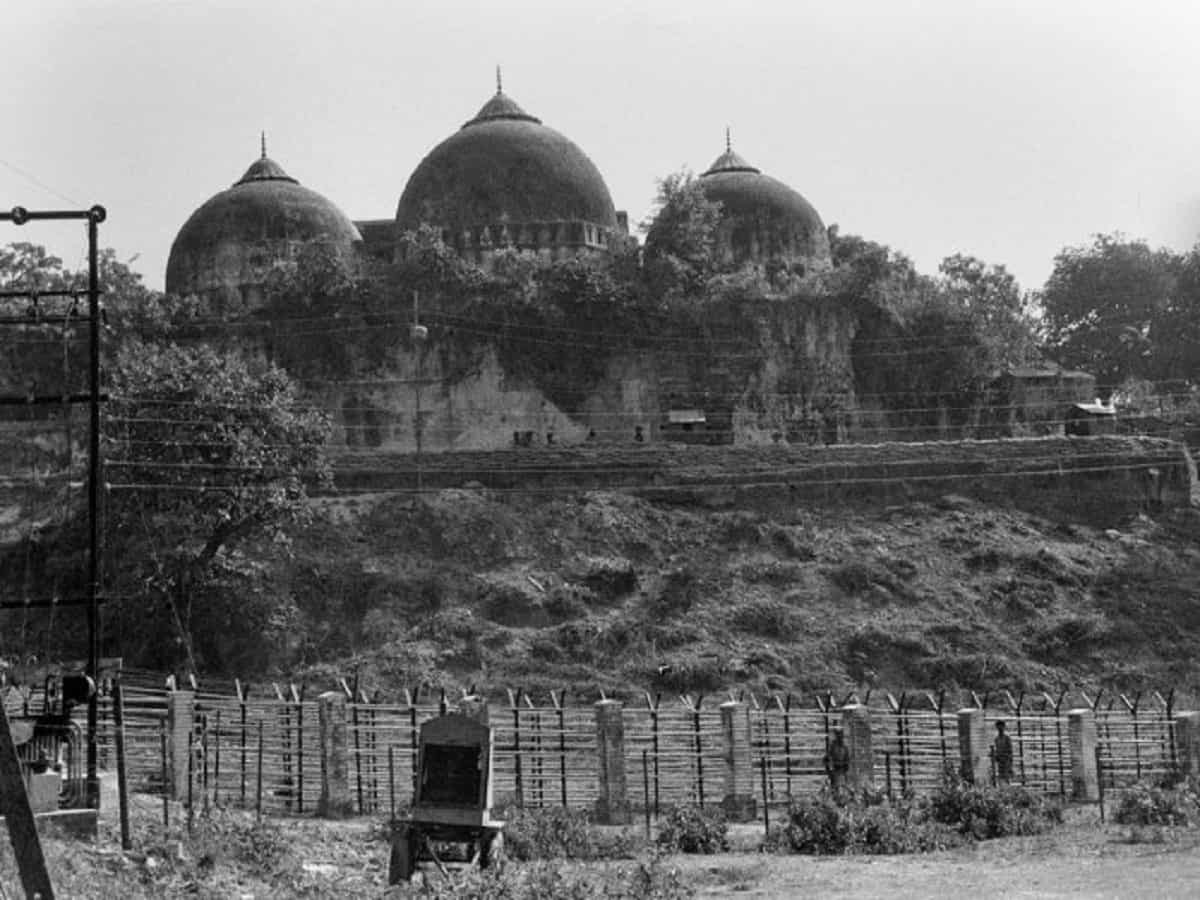

New Delhi: Nearly three decades, 850 witnesses, more than 7,000 documents, photographs and videotapes later, a court in India found no-one guilty of razing a 16th-Century mosque which was attacked by Hindu mobs in the holy city of Ayodhya.

Among the 32 living accused were former deputy premier LK Advani, and a host of senior BJP leaders. Wednesday’s court judgement acquitted them all, saying the destruction of the mosque in 1992 had been the work of unidentified “anti-socials” and had not been planned.

This was despite numerous credible eyewitness accounts that the demolition, which took just a few hours, had been rehearsed and carried out with impunity and the connivance of a section of the local police in front of thousands of spectators.

Last year, India’s Supreme Court conceded it had been a “calculated act” and an “egregious violation of the rule of law”.So how do we explain the acquittals?Generally the verdict is being seen as another indictment of India’s sluggish and chaotic criminal justice system.

Many fear it has been damaged beyond repair by decades of brazen political interference, underfunding and weak capacity.But more specifically the verdict has thrown into sharp relief the increasing marginalisation of India’s 200 million Muslims.Under Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist BJP government, the community has been pushed into a corner and feels more humiliated than at any time in the history of pluralist, secular India, hailed as the world’s largest democracy since independence in 1947.

Mobs have lynched Muslims for eating beef or transporting cows, which are sacred to majority Hindus. Mr Modi’s government has amended laws to fast track non-Muslim refugees from neighbouring countries. It has split the Muslim-majority state of Jammu and Kashmir and stripped it of its constitutional autonomy.

This year, Muslims were singled out and blamed for spreading the novel coronavirus after members of an Islamic group attended a religious gathering in Delhi. Larger Hindu religious gatherings during the pandemic received no such political, public or media opprobrium or scape-goating. That’s not all. Muslim students and activists have been picked up and thrown into prison for allegedly instigating riots over a controversial citizenship law in Delhi last winter, while many Hindu instigators went scot-free. The Babri verdict, many Muslims say, is just a continuation of this humiliation.The sense of alienation is real. Mr Modi’s party makes no bones about its Hindu majoritarian ideology. Popular news networks openly demonise Muslims. Many of India’s once-powerful regional parties, which once stood by the community, appear to have abandoned them. The main opposition Congress is accused by critics of using Muslims cynically to harvest votes without providing much in return. The community itself has few leaders to speak up for it.”Muslims are simply losing faith in the system. They feel cornered and feel the political parties, institutions and the media are failing them. There is a lot of despondency in the community,” says Asim Ali, a research associate at the Centre for Policy Research, a Delhi-based think tank.

In truth, India has a long history of marginalising Muslims. They “carry a double burden of being labelled as ‘anti-national’ and as being ‘appeased’ at the same time”, according to one report. But the irony is that, while many Indians have bought the Hindu nationalist bogey that Muslims are being unfairly rewarded, the community has not in fact benefitted from major socio-economic gains, say historians.Muslims are disproportionately squeezed into ghettos in India’s teeming cities. Their share in India’s elite federal police officers force was below 3% in 2016, while Muslims make up more than 14% of the population. Only 8% of India’s urban Muslims had jobs which paid a regular salary, less than double the national average, one report found.