Amid continuing reports of media under pressure and fears of severe curbs on freedoms, a recall of the country’s worst phase of democracy seems in order for the benefit of the younger generation, for which it might just be a piece of history.

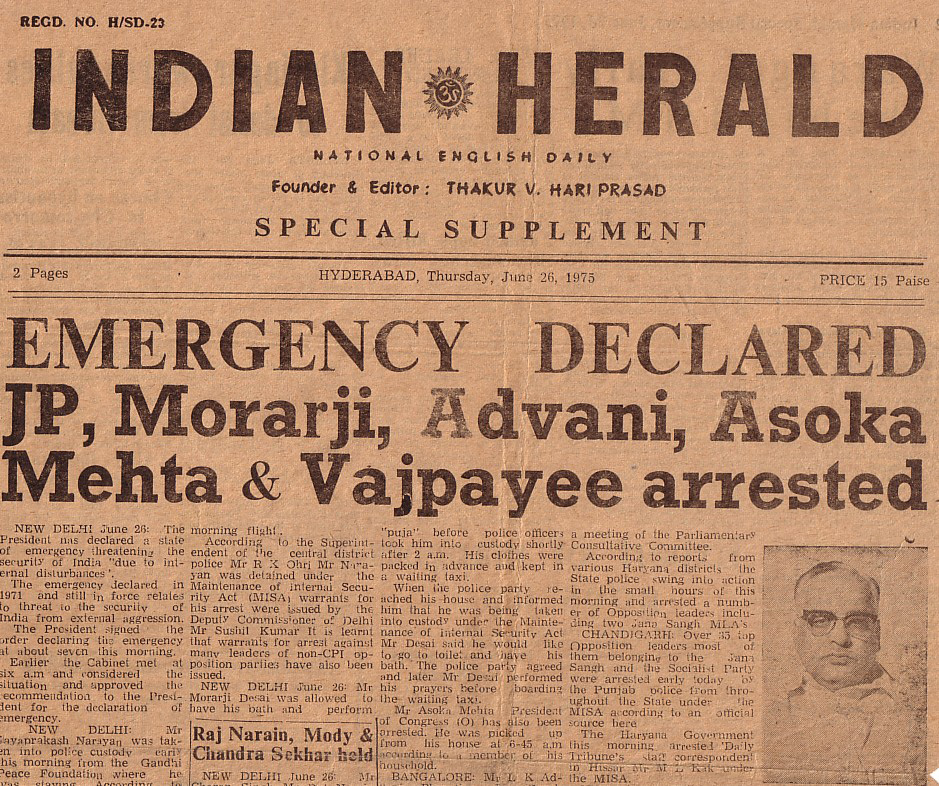

It was on that portentous midnight of Wednesday June 25, 1975 – 45 years to the day — that the dreaded internal emergency was clamped. I was a reporter in The Indian Express at Hyderabad. To be in the Express those days was something. You were a marked man and your paper too ditto because of the vigorous support extended to the Save Democracy movement of Jaya Prakash Narayan. There were widespread fears that Government would ride roughshod over the Press. These fears were amply justified when internal emergency was declared, all freedoms and rights throttled, opposition leaders put in jail and the press censorship imposed.

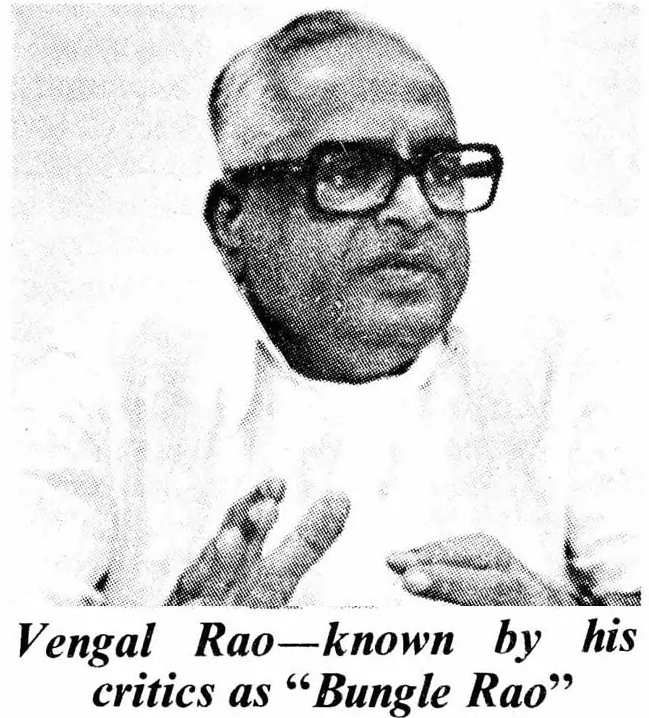

I did not pay attention to the hush hush talk in the bus as I commuted to the Secretariat that day. I learnt about the development only after reaching the Secretariat where the Chief Minister J. Vengal Rao was scheduled to address the press shortly. He was nice, as usual. The expression ‘nice’ needs explanation. Some of us feared that the Chief Minister, now freshly armed with all powers, might be a different man. No. He was as his usual self – cordial and matter of fact.

It is a known fact that The Indian Express had defied the emergency curbs by keeping the editorial slot blank to register its protest. It also unsubscribed PTI and UNI news agencies and ran the paper entirely on its own reporting network – Express News Service, ENS. The ENS was headed by Kuldip Nayar. The veteran journalist was in Hyderabad a few weeks later for an interview with the Chief Minister.

I found Kuldip Nayar to be incredibly downright and simple. I felt honoured and humbled when he asked me – junior to many in the bureau – to give his copy a glance over for possible mistakes!

Those days the Information and Public Relations people issued press notes and advisories not to use this item or that. Sometimes these advisories turned out to be valuable because we followed them up and got a good report.

The Express bureau – the Hyderabad edition was yet to come – was in the Skyline theatre lane in Basheerbagh, while the edition was based in Vijayawada. A government official at Vijayawada was designated to clear the pages before they were sent to the press. He would take his own time as a government file pusher.

Here is a tale of courage during those days of fear and tension. The unlikely hero was Pratap Kishore of Deccan Chronicle. We were at the National Institute of Rural Development (NIRD) at Rajendranagar for a press conference by the Union Minister Babu Jagjivan Ram. We waited endlessly for the briefing, but the Minister would not turn up. We got up to stage a walk-out, brushing aside the pleas of the PRO. But wiser counsel prevailed. Who would walk all the way back to office? (We were herded to the place in NIRD bus). When the Minister finally showed up two hours later, Pratap stood up and said, ‘Sir, the emergency is supposed to have infused discipline and punctuality at all levels in the country. How come you are late by two hours?’.

Jagjivan Ram blew his top and said ‘you know as ministers we have a hundred things to do.’

We learnt later that Jagjivan Ram gathered info about the ‘errant’ reporter and asked the Chief Minister to ‘fix’ him. Vengal Rao called some of our senior people to persuade Pratap to be careful in his own interest. The CM informed Jagjivan Ram that action was taken on the reporter. In fact, no action was taken; it was only for the Minister’s Jagjivan Ram’s consumption. Vengala Rao had been largely fair to us during the time.

Dasu Kesava Rao is a seasoned journalist who has worked, among several newspapers, with The Hindu and served as its Bureau Chief in Hyderabad.