This is not the title of a best-selling book or a movie. It is the true account of a man who had travelled from Madras to Kasi via Hyderabad and back. This he did nearly two hundred years ago when a long journey on a road less travelled meant vagaries of weather, threat from wild animals and thugs.

Motivated by a strong desire to undertake the pilgrimage, Yenugula Veeraswamy left Chennapatnam (Madras) on May 18, 1830 and returned on September 3, 1831 in ’15 months, 15 days and 10 minutes.’ His entourage comprised family members, relatives, palanquin bearers, boyas, luggage carriers, cooks and others numbering about 100. They travelled in palanquins or carts and used dolis to negotiate hillocks.

In addition to fulfilling his spiritual obligations, Veeraswamy documented the history, culture, language, economy besides the lifestyle, customs and manners of the people en route.

Who is this Veeraswamy?

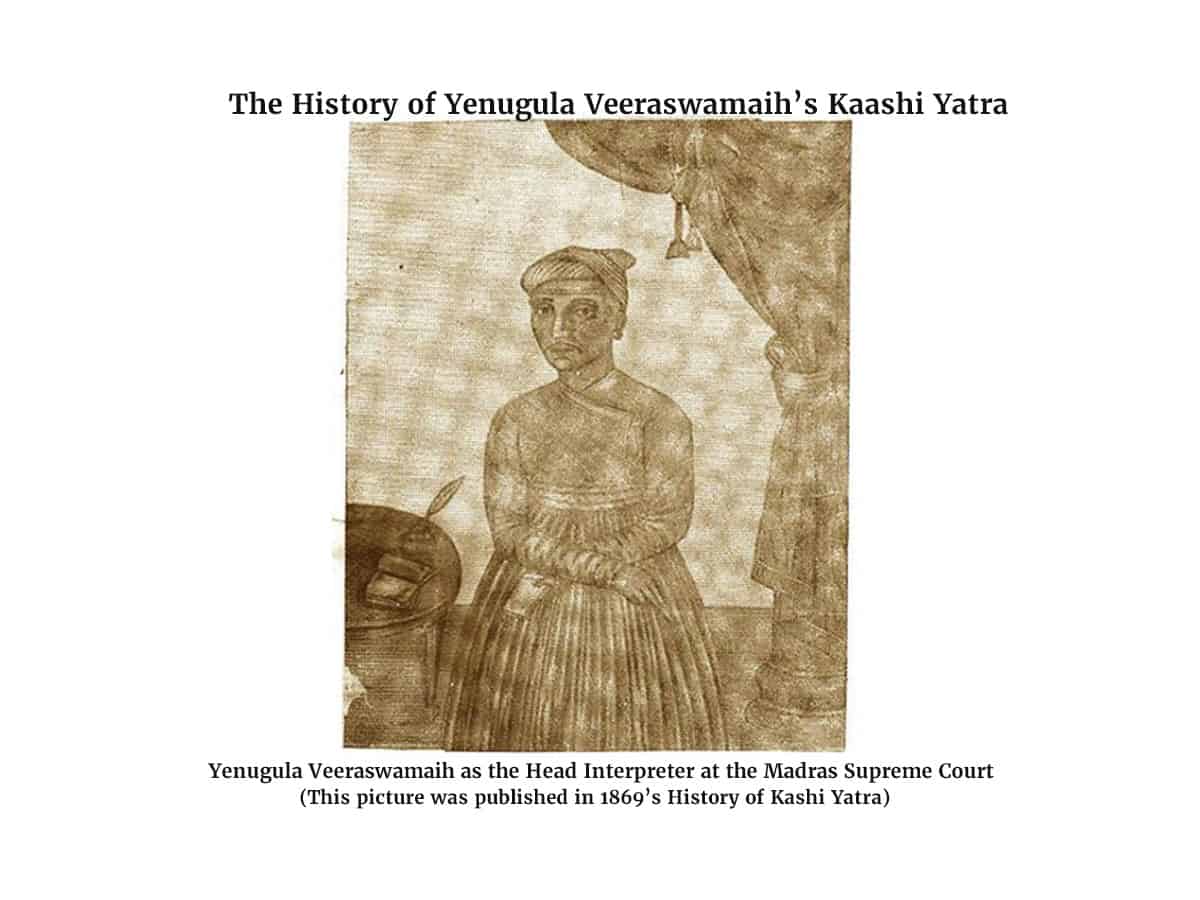

Having mastered English at very young age, he joined the Collectorate at Tirunelveli as interpreter and rose to become the chief interpreter at the Supreme Court in Madras. His British masters held him in high esteem.

He reached Kasi via Tirupati, Cuddapah, Srisailam, Hyderabad, Nagpur, Jabalpur, Mirzapur, Allahabad and on return trip covered Ghazipur, Chapra, Patna, Gaya, Calcutta, Puri , Srikakulam and Nellore.

In his journal, published by his friend Komaleswarapuram Srinivasa Pillai in 1838 and again by historian Digavalli Venkata Siva Rao in 1941,Veeraswamy provides illuminating insights dating to the early 19th century. He wrote to C.P.Brown, legendary Telugu scholar and lexicographer, about his experiences.

Life in Hyderabad

The Veeraswamy cavalcade reached Hyderabad via Srisailam at 9 pm on June 29, 1830, covering the last 12 miles from Shapur in six hours! What was life like in the Asaf Jahi capital? He recounts thus…….

The party camped at Begum Bazaar. The city was observing the ninth day of holy Muharram. ‘The place attracts thousands of people of other faiths too. It was a great day. I thought I had entered a sacred place and was thankful to the Lord.’ He describes Begum Bazaar as an urbanized area where the British Resident resides in ‘a splendid and spacious mansion constructed at the expense of the Nizam’. People and traders constructed houses around the haveli, making it a developed area known as Chandraghat. Shahukars set up shops at Karuvana (Karwan) where diamond merchants resided. Brahmins lived in Shali banda; the Dewan Peshkar Chandulal also made it his place.

The Nizam’s devdi was located in the middle of the city where the amirs going by the name of umrahs, traders also resided. ‘Mecca Masjid, a Muslim shrine, is to be found in the centre of the city. Two of the minars of the masjid are plastered and are visible even at long distances.’ The Veeraswamy diary also mentions karanjis excavated by Dewan Miralam and the chowk housing cloth and other shops.

‘There is a great chavadi with four entrances at the intersection of four ways with great sthupees. (presumably a reference to Charminar)’. The city had witnessed devastating flood in the river Muchkunda or the Musi the year before. The floods breached a bridge constructed by the British at Delhi Darwaza. The Nizam built a new bridge strong enough to allow a large herd of elephants to pass safely.

The City was not very safe for outsiders because ‘every person is armed and the milder ones are beaten up or cut down. Therefore, when outsiders use mounts, they have to take with them armed escort, particularly people who are tough in talking and tackling people.’ The city also teemed with fakirs who demanded alms. Passing travellers were cheated in money exchange; even legal tender was refused on one count or the other unless a handsome commission was agreed to.

Veeraswamy and company moved from the shahr to Dandu (Secunderabad cantonment where the British Army was stationed) on July 8. Between the shahr and dandu, ‘there is a great tank by name Hussainsagar. A fine road has been laid on this tank for use by the English moving in horse carriages.’ Armed men stood at both ends to ward off the natives or Mughlai vehicles from spoiling the aesthetic beauty of the place.

He noted that in contrast to the shahr, life was orderly and secure in the cantonment area. People could seek and get justice at the Kotwal chavidi. This was one reason why people and traders preferred to live in this part of the city. At Srisailam, he found the ancient shrine in ruins and daily rituals not performed.

Logistics for journey of such scale demanded remarkable organizational abilities to overcome challenges. It was not easy find to accommodation and food supplies for the large entourage, besides protection to life and property. On some occasions, he hired armed men for the purpose. Letters of recommendations from the Chief Justice and other higher-ups helped him considerably.

Veeraswamy was a kind man. At Prayag, he helped all the members, including servants, to fulfil religious obligations, at his expense and had 40 barrels of sacred Gangajal sent to Chennapatnam for the benefit of the multitude of devotees back home.

Veeraswamy planned to write the travelogue in English too, but death foiled the plan. He died in 1836 at the age of 66. This task was accomplished in 2000 by the AP Government Oriental Manuscripts Library and Research Institute.

Since ancient times, travelers from Asia and Europe toured the length and breadth of India and documented their experiences. These accounts, written from their perspective, formed basis for writing Indian history. Not many travelers within the country had chosen to record their experiences.

Yenugula Veeraswamy is indisputably the first Telugu man to write a travelogue which is a significant milestone in Telugu literature.

Dasu Kesava Rao is a seasoned journalist who has worked, among several newspapers, with The Hindu and served as its Bureau Chief in Hyderabad.