Sruthi Vibhavari

Going back a century

On Tuesday July 14, the USA’s top infectious disease specialist, physician-scientist Dr. Anthony Fauci said that the COVID-19 pandemic could be as deadly as the 1918 Spanish Flu. During the Spanish Flu, it is estimated that about 50 to 75 million people died around the world.

10 to 12 million of those deaths were from India only.

“I hope that such a situation does not materialize, but the current signs indicate a possibility of a similar situation of that magnitude,” Fauci, the Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases said.

It is indeed a matter of concern if COVID-19 assumes the intensity of the Spanish Flu. Currently, confirmed COVID-19 positive cases stand at 13.8 million, with 5,90,000 deaths.

The First Wave of the Spanish Flu

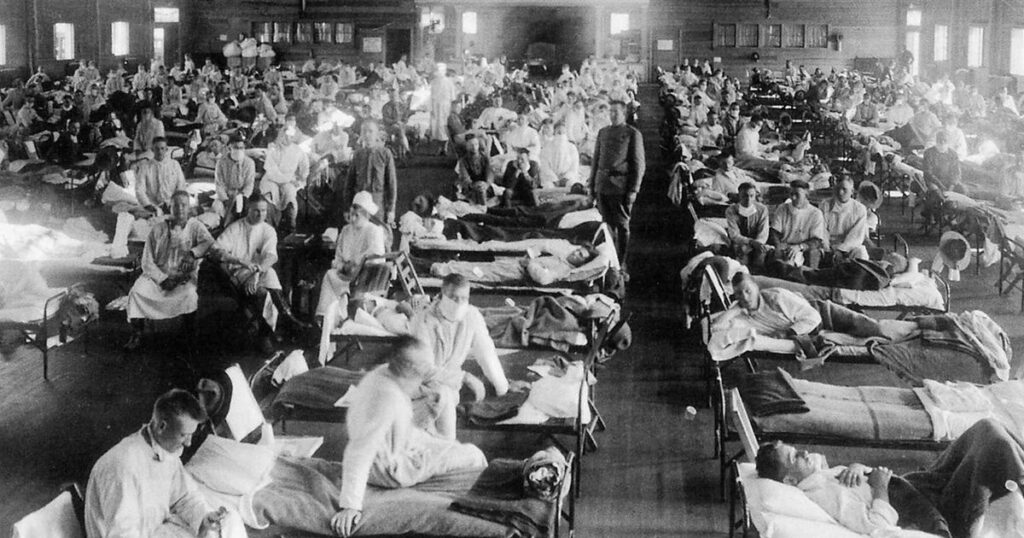

The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, the deadliest in history, infected an estimated 500 million people worldwide — about one-third of the planet’s population. It killed more people than in the World War.

Influenza, caused by the H1N1 virus, reached Bombay in late May. India experienced two distinct waves — a mild first one in the summer of 1918 and a lethal second one in the late autumn cum early winter.

The first wave of the pandemic that hit India was not particularly deadly. The spread was sporadic and only a handful of cases were registered in the Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta provinces. British officials took note only when some of their workers were affected. A report noted, “As the season for cutting grass began … people were so weak as to be unable to do a full day’s work.”

A Deadlier Second Wave

The second wave began in September 1918. Bombay was still the epicenter, but because of the commercial activities aided by the transport systems, the virus spread to northern India and even towards the south reaching Sri Lanka. Catastrophe and death overwhelmed cities and rural areas alike. Indian newspapers reported that crematoria were receiving 150 to 200 bodies per day. The Associated Press reported that Calcutta’s Hoogly River was ‘choked with bodies’ and ‘streets and lanes of India’s cities are littered with the dead.’

Mahatma Gandhi, who was 49 then, also got infected. His younger son and daughter-in-law died after days of getting infected. Over the period of 1918-19, the fatal virus wiped out nearly four per cent of the Indian population. It is known that every second person infected succumbed.

Different diseases, yet important lessons

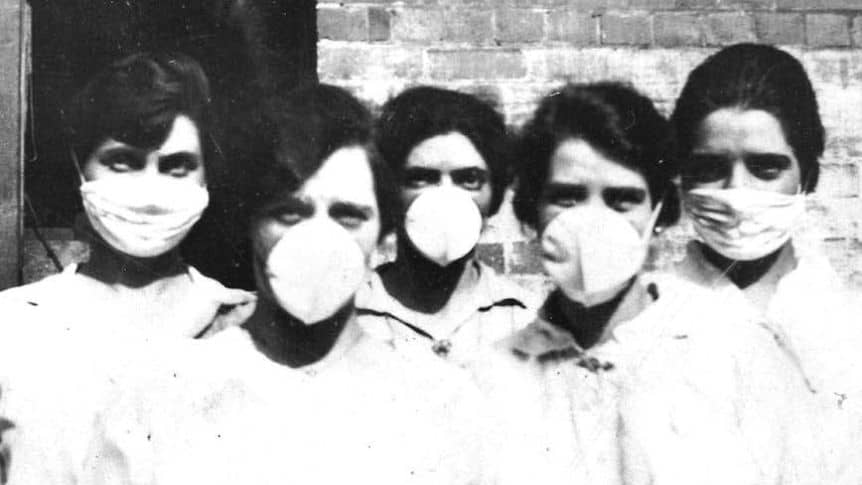

Apart from grappling uncertainties that are prevalent, both the Spanish Flu and COVID-19 share similarities in the ways they are transmitted through the surfaces they land on and the way they cause respiratory failure. Non-pharmaceutical interventions such as physical distancing measures and usage of masks also were the lessons the 1918 pandemic taught.

However, they are biologically different. Influenza has higher mutation possibilities because of the errors during replication in the RNA (ribonucleic acid), while the Coronavirus corrects duplication which decreases their relative mutation rate. Influenza also circulates more during winters because of its seasonal character and it is currently unknown whether COVID-19 will be influenced by seasonal changes. Also, half of the influenza-related deaths were caused in the 20 to 40 age group, which does not seem to be the case now.

So far, the spread of COVID-19 has been hard to predict. The stark differences of it in relation to the 1918 pandemic is a reason why the spread of the latter is not the template for what will happen with Corona in the coming few months. The end of influenza in 1919 does not portend the end of COVID-19 in 2020.

People, though, will continue to seek answers from the medical history of Spanish Flu especially because it disappeared without any vaccine (the influenza vaccine was invented only in the year 1942).

The end of the pandemic was attributed to people developing herd immunity, which is defined as the ability of a population to resist infection by a pathogen.

Through a novel pandemic like COVID-19, behavioral attitudes to disrupt the transmission as noted in the Spanish Flu history, assume significant importance. Sticking with the hygiene practices and restrictions in place would prohibit a second wave from emerging. It is only wise to kill the recklessness and nonchalance before it grows further, to prevent history from repeating itself.