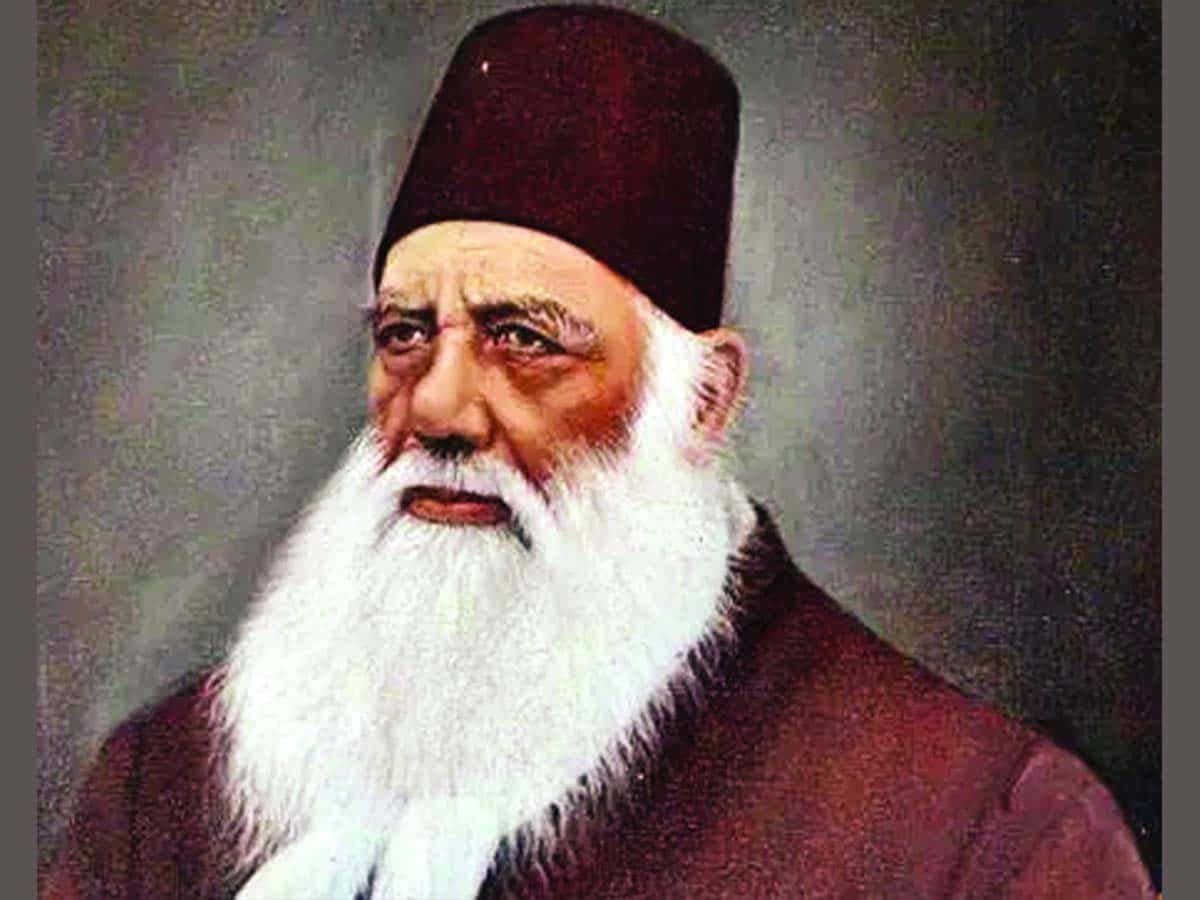

Several years ago when Aligarians of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, were furiously engaged in their traditional annual feud and more frequent conventional clashes of little egos over Sir Syed Day celebration, an Osmanian friend of mine publicly attacked the Aligs for “disgustingly” claiming to be the “best alumni community of India”, and challenged the assertion that Sir Syed “alone” was the pioneer of Western education among Muslims of India. This invasion of Aligarh turf enraged a very senior Aligarian so much as to declare that “agar Sir Syed na hotay tau Hindustan ke Musalman jootay gaanth rahe hotay”(If Sir Syed were not there the Indian Muslims would have been nothing more than shoemakers). The Osmanian, already incensed by the Aligarians’ endless internecine quarrels on non-issues, and tall claims, retorted with a vengeance: “Aap loag jootay gaanth rahey hotay, hum tau aisay hi parhay likhay hotay jaisay ab hain” (You would have been making shoes but we would have been as educated a community as we were then).

This debate provoked me to write a brief article for the Osmania Jubilee Souvenir, wherein I argued that Aligarh Movement (mind it, not the AMU) was the mother of all other “Muslim” universities and that all other “Muslim” universities in South Asia are its daughters, even those which were established in opposition to Aligarh or to the personality of Sir Syed, like the Jamia Millia Islamia and Osmania University itself. After reading my article in the Osmania Jubilee Souvenir, an alumnus of Bombay’s Muslim-run Maharashtra College told me that the alumni of his college call it “Little Aligarh”.

Few people, including the Osmanians, know that Osmania University was established to “eliminate the bad impact of Sir Syed’s anti-Islamic nechri thought” on Muslim youth. This was mentioned by Egyptian modernist scholar, Muhammad Abduh, in the preface of a monologue written by his mentor, Syed Jamal Ad-Din Al-Afghani, and re-published by Jurji Zaidan in his Al-Hilal magazine.

In the late 1800s, Afghani was in India for a few months and stayed in Hyderabad during the reign of Mir Mahboob Ali Khan, the sixth Nizam. There he came to know about Sir Syed’s non-conformist religious thought and their feared impact on the uninitiated minds of students of the MAO College. Afraid of the dark future of the Muslim youth of India, Afghani suggested to the reigning Nizam to open a new university where western sciences were taught while at the same time the Deen of Muslim youth could be protected. The Nizam agreed and ordered a feasibility study. But he died young before Afghani’s Indian dream could take shape on the soil of Hyderabad. The Osmania University was, however, opened by the sixth Nizam’s son, Mir Osman Ali Khan, the seventh Nizam. No wonder it was named after the then reigning Nizam, and not as Mahboobia University, thanks to the ethics of dynastic autocracy. So, in my opinion, Osmania was a daughter of Aligarh as much as Jamia Millia and/or Islamia Colleges of Calcutta and Peshawar are. Even Nadwatul Ulama, for that matter, is a daughter of Aligarh since many top Ulama of Deoband as well as Shibli Nomani established it on the plea that Sir Syed’s college had strayed away from the right course. Many of Sir Syed’s companions, including my own great-grandfather Maulana Abdullah Ansari, were among the founders of the Nadwa, according to documents preserved in the archives of Nadwa as well as Madrasa Saulatiyah, Makkah.

Nonetheless, the “conflict” sparked by Afghani had one positive note about it: sincere difference of opinion in matters of higher social-political goals always results in greater achievements.

My logic silenced both the Osmanian and the Aligarian, but I was disappointed to note that no one paid attention to the madrasa, its history and role in Indian society while discussing Muslim academia in South Asia.

Does anyone believe that the Muslims of India would still be reduced to societal cobblers if they had not the good fortune of having a man like Sir Syed?

I don’t think so.

Darul Uloom Deoband, for example, was established nine years before the MAO College and had already sent out four batches of graduates when Aligarh was enrolling its first batch to start study. And don’t forget that unlike Jamia, Osmania and Nadwa, Darul Uloom Deoband was not established in reaction to Sir Syed’s academic philosophy, nor was the Aligarh College established in reaction to Deoband’s emphasis on deeni sciences, with logic-philosophy and astronomy taking a back seat. That is very important point that I will discuss later in this article. So, the point is that even if there was no Sir Syed, the Muslim of South Asia might still be educated and perhaps the “traditional” ulama might have been better equipped scientifically than those who came out of the other parallel stream of Asian Muslim academia particularly since the region’s regaining of independence in 1947. But then, the same is true about Aligarh. Look at the galaxy of prominent Aligarians that had studded the South Asian sociopolitical firmament in pre-partition days: Sahibzada Aftab Ahmad, Sir Ziauddin, Raja Mahendra Pratap, Muhammad Ali Jauhar, Hasrat Mohani, Mohammad Habib, Babar Mirza, Hadi Hasan, Zakir Hussain Khan, Yusuf Hussain Khan, Abdul Majid Daryabadi, Iqbal Suhail, Rasheed Ahmad Siddiqi, Rafi Ahmad Kidwai, Hafiz Muhammad Ibrahim, Liaquat Ali Khan, Sardar Abdur Rab Nishtar, Khwaja Nazimuddin, Baba-e Urdu Abdul Haq and Ayub Khan etc. The pre-independence list is very long. But after the independence, the AMU too did not produce men of that same old caliber. Its post-partition output is no better than graduates like me. The situation on the other side of our fractured academia is no different.

Nonetheless, before the advent of what we know today as “Western” education, India of the Mughals and even before the Muslim era, was not a land of illiterate, uncivilized “aborigines” as we find sets of people condemned as such on the two shores of the Pacific. India of Pre-Muslim era had produced a mathematician like Aryabhata the Elder (476-550) and a social scientist like Chanakya (d. 283 BC) – one has every right to disagree with the latter’s ruthless political philosophy even though modern, civilized politicians of all persuasions and religions have been faithfully toeing the line drawn by Chanakya and his European counterpart Machiavelli (who took another 1700-plus years to make a name for himself) in spite of your and my disagreement with their literally cut-throat ideologies.

Once Muslims rose to political power in South Asia, they gave human intellectual heritage such names as Albiruni, Abul Fazl, Faizi (again you have every right to disagree with the many opinions held by Abul Fazl and Faizi) and the greatest of them all, Shah Waliullah, and finally our own dear Maulawi Syed Ahmad Saheb ibn Syed Muttaqi.

But before we miss the coordinates in these uncharted oceans of knowledge lost somewhere in our backyards, let me make it clear that none of these persons was the product of an Oxford or a Harvard. So what? The South Asians were not living in Stone Age when Warren Hastings was dreaming of starting the Calcutta Madrasa, when Jonathan Duncan was thinking of establishing the Benaras Hindu College, and when Lord Wellesley was contemplating approval for a Fort William College – all forerunners of our own dear Syed Saheb’s Madrasatul Uloom Musalmanan.

We already had madrasas! And the Muslims were not mending chappals. Just the contrary.

Let me quote here from one of my earlier papers on the history of madrasa: Sir William Henry Sleeman, a contemporary of British-Indian official Lord Macaulay, had a different European observation about the madrasas. In January 1836 he said: “There are not many nations in the world who provide such vast educational opportunities as Muslims of India do”. In his ‘Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official’, Sleeman added that “India’s Muslim people provided education of such high standard to their sons that was appropriate for a prime minister” (Nazir Ahmad, Urdu Fiction Per Maghribi Asaraat, Aaindah monthly, Karachi, Pakistan, December 2000, p57). And Sleeman is speaking about the system that was not imported or evolved by the colonial British rulers.

This resolves once again the controversy whether Muslims of South Asia would be repairing shoes if there was no Sir Syed. Although it is uncertain if Syed Al-Afghani would still write the monologue in rejection of Syed Al-Hindi’s “nechri aqaed” and draw the attention of an Indian princely ruler to open a university in Hyderabad (zidd mayn Aligarh ki) in order to eliminate the threat to Muslims becoming cobblers. No, nothing of that sort would have happened. Therefore, Sir Syed’s emergence at the Indian horizon of the nineteenth century was a stimulus rather than a reaction, something different from the assertion and counter-assertion of the Jeddah Aligarian and Osmanian. But then he was a stimulus of what; and in view of the educational situation of the country prevailing in the mid-nineteenth century, what’s so fantastic about Sir Syed?

The problem with our dear Syed Saheb was that in his zeal and the urgency he felt to bring his people on par with the new rulers’ thinking and practical application of their scientific theories, he betrayed such radical thoughts that helped him to be easily misunderstood by contemporary Muslim masses who were already alienated dexterously by the Laat Sahibs. Another problem with Sir Syed was that some of his well thought-out sociopolitical opinions were rejected by his disciples, companions and successors within two years of his death and a totally new political milieu was created before the end of the first decade of the new century.

To be continued…

Indian-Canadian Tariq Ghazi is a veteran journalist and writer based in Toronto. He is also the Director of Umam Studies House.

Mr Ghazi can be contacted at m.tariqghazi@gmail.com