In the late 1990s I landed up a reporter’s job with Mumbai edition of The Asian Age. Since I was young, raw and ready to do whatever came my way, the newspaper’s feature team too would give me some assignments. I began to enjoy writing feature articles as they gave me liberty to be creative, do some research and meet fascinating people from fields such as films, theatre, music, art, poetry, fiction, non-fiction. Soon, the features’ editor got me moved from reporting to the features’ team.

Nawab Jaffar Imam who resided and resides at the sea-facing beautiful bungalow Belha Court near the iconic Taj Mahal Hotel in South Mumbai was fond of Sufi soirees and book reading sessions. He had also partnered with a Catholic gentleman with roots in Goa (now I forget his name) to establish a PR agency. It had acquired some big names in the city as clients.

At one of the events his agency was managing, Nawab Sahab introduced me to his son Moin Mir.

Tall, dashing, well-dressed, curly-haired, Moin smelt of nawabi upbringing, but unlike many bigda nawabzade, he was humble and modest to a fault. It is because of him that I got to see a horse racing event for the first time in my life at Mahalaxmi race course. I remember visiting his house once where I was treated with succulent shaami kebabs and a variety of other snacks. We would often run into each other at social and cultural gatherings.

Then Moin suddenly disappeared from Mumbai. Nawab Sahab told me Moin had moved to Newzealand where he was planning to settle down. With Moin, Nawab Jaffar Imam’s only child, settled abroad and substantial property, both inherited and earned with his sweat and blood, at his disposal, the ageing Nawab sahab didn’t need to work. He practically retired and spent time in reading and writing. I moved to other papers and we lost touch.

After two decades or so, I bumped into Moin again, this time at Times Lit Fest at the Mahboob Studios in Bandra a couple of years ago. His once jet black hair had turned salt and pepper though he retained his old charm. He was no longer a PR professional I had last seen him as. He was there as one of the participating writers. I attended the session that he enthralled with his talk about his debut book Surat: Fall of a Port, Rise of a Prince. The book is about one of his ancestors who went all the way from Surat to the English Parliament to fight for the rights of Indian princes. It received critical acclaim. Despite my protests, his father bought me a copy of this book at the festival. In brief conversation, Moin told me he had settled down in England. We exchanged email addresses and other contacts and said goodbye. Nawab sahab promised a feast of kebabs at Belha Court. But then the pandemic came and, despite living in the same city, we have not met since.

Moin went back to England without giving a hint that he was working on his second book. This summer social media informed me of Moin Mir’s novel The Lost Fragrance of Infinity(Roli Books). I immediately booked a copy through Amazon.

To read this fascinating book is to get insight into the ishq or love, the devotion to divinity and the inclusivism that permeate the world of Sufis.

I can’t claim I have read a lot about Sufism but know a thing or two about it. But never before had I looked at the magnificence of Sufism the way Moin persuades us to.

His protagonist Qaraar Ali is a craftsman, master in creating tiles, and a seeker of Sufi thought when Nadir Shah perpetrates a barbaric massacre in Delhi in 1739. But before the marauding Nadir and his troops turns Qaraar Ali’s life upside down, forcing him to flee to central Asia, from where he goes to Persia, Turkey and then Andalusia, Spain, Qaraar Ali has all the joys that life can give to a gifted craftsman, a passionate lover and a seeker of knowledge. It is his luminous mind more than what he creates with hands– the tiles–that draws Abeerah, daughter of Shahbaz Khan, a general in emperor Muhammad Shah’s army, to him. In racy and lucid prose, Moin describes the girl: “Abeerah was of medium height with long, flowing tresses reaching her curvaceous hips. Her hands were smooth and delicate.” Are we watching a movie or what?

It is such delightful descriptions, the sweep of time and age, the many territories it covers and issues it tackles that has earned the novel critical acclaim. For a debut novelist, Moin has earned praise from the likes of William Dalrymple, Shashi Tharoor and Rana Safavi. He has been in conversations with literary historian Rakhshanda Jalil and writer and Supreme Court lawyer Saif Mahmood. He is a toast of online literary festivals. Several publications have carried the reviews and there are photos which suggest how youngsters have had “selfie moments” with him at bookshops in London.

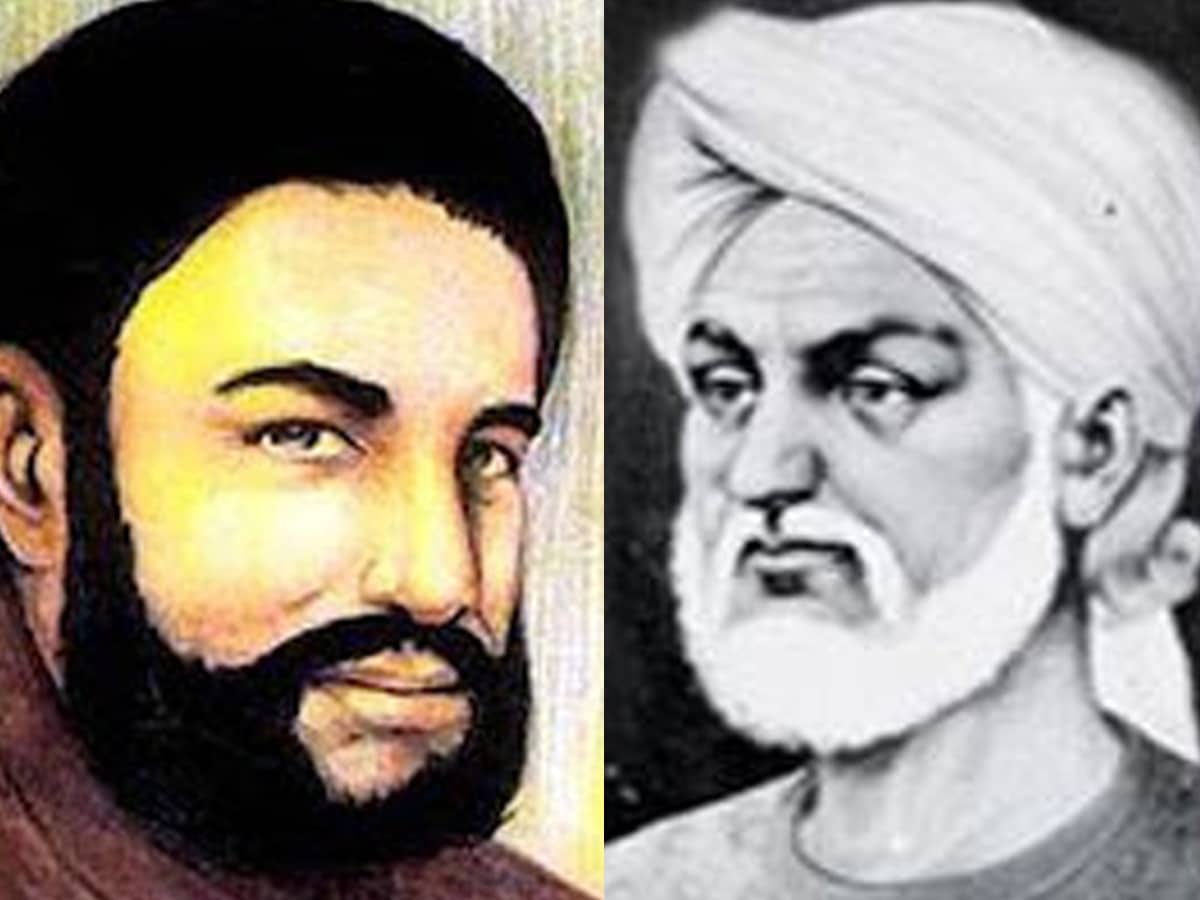

Instead of writing yet another non-fiction tome on Sufism, Moin took the route of a novel. Through Qaraar Ali’s journey, his triumphs and travails, his encounters with Sufi masters and love for knowledge and scholarship, the novelist gives insights into the great accomplishments of geniuses like Rumi, Omar Khayyam, Ibn Arabi.

It is surreal to see free-minded Urdu poets like Mir, Dard and Sauda holding forth on life’s myriad dimensions sitting on the steps of the Jama Masjid. In a way the novel also gives glimpses into a syncretic ethos, the famed Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb or composite culture that Mughal India represented.

Most importantly, Moin succeeds in reclaiming the lost voice of Sufis. In several interviews and talk shows Moin has said how he felt exasperated at the popular image of Sufism. That Sufism is about visiting Sufi shrines, offering chader and flowers, listening to Sufi music and qawwalis.

Not many care to know that Sufi masters were also great mathematicians, astronomers, geometry experts and poets. They challenged the hold of the Muslim clergy who tried to hijack the faith. Mincing no words, the novel questions how the faith has been misrepresented, rituals have taken over reason and scientific temperament has been replaced with totems.

I am so glad that a privileged and prosperous childhood didn’t spoil Moin. In a recent, long conversation on telephone, his father told me how Moin, as a child and an adolescent, would sit with his grandfather and observe as the learned man discussed Ghalib, Rumi, Omar Khayyam and Iqbal with the likes of scholar Dr Rafiq Zakaria and journalist Khushwant Singh. Moin didn’t allow that early exposure to talks about works of literary giants go waste and scoured libraries to read up on the Sufi masters. He travelled extensively and even learnt Farsi or Persian from an Iranian friend in London to understand the poetry of Rumi, Hafez and Saadi before he sat down to write this novel. Hats off to Moin for giving us such a beautiful book which helps calm the nerves and soothes the soul in these disruptive times.

Mohammed Wajihuddin is with the Times of India, Mumbai. This is his blog which he uploads on Facebook.