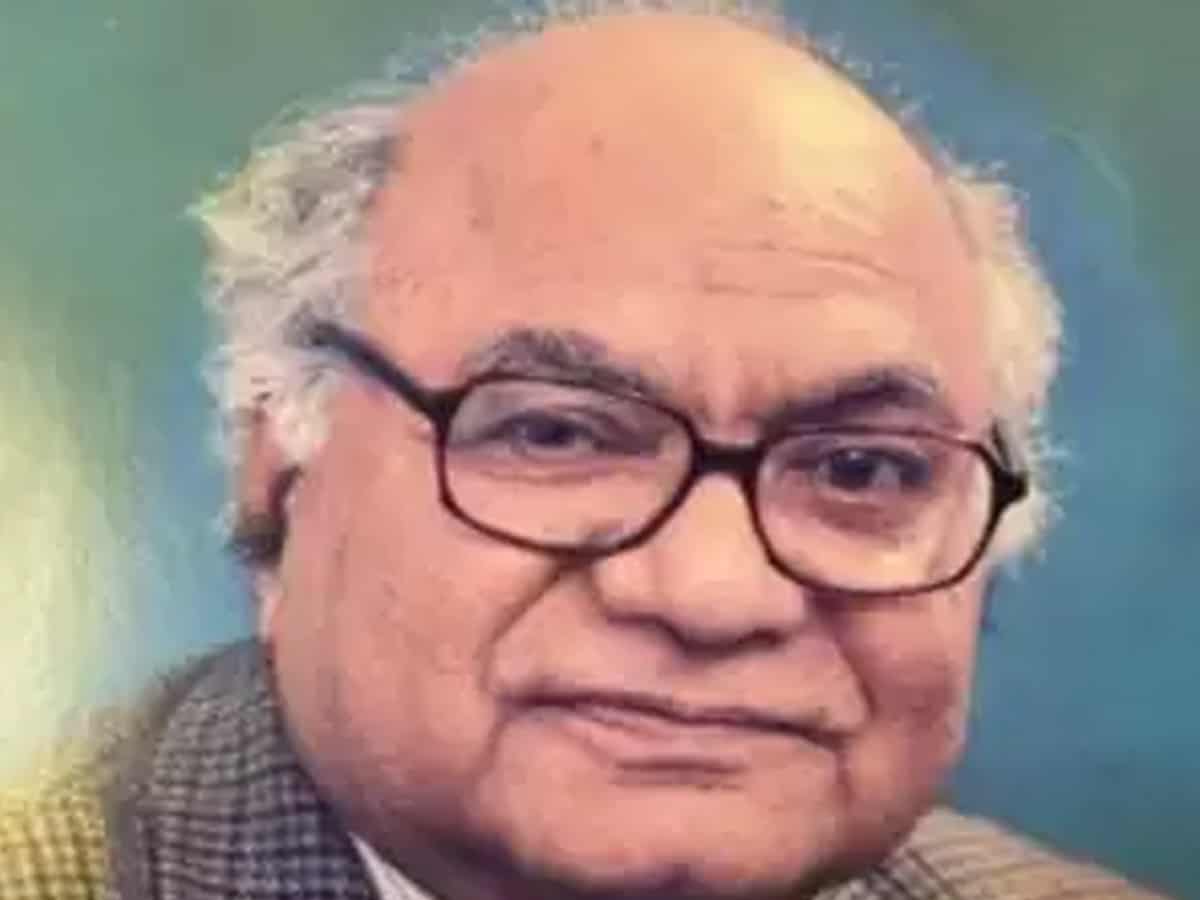

October 30 is the first death anniversary of noted economist, former head and chairman of the Department of Economics at McMaster University, Canada, Prof Syed Ahmad. An alumnus of Jamia Millia, Patna University, Aligarh Muslim University and London School of Economics, Ahmad taught at universities in Aligarh, Khartoum (Sudan), Kent (England) and McMaster (Canada). He was a visiting professor at many other institutions and has left a legion of students and admirers across the globe.

Syed who passed away at the ripe age of 90 recently counted former Indian Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh among his friends. He is profiled in “A Biographical Dictionary of Major Economists (1700-1986)” and was also among “Who is Who in Economics.”

Once Syed Ahmad reached a bookshop in Muzaffarpur and inquired about some books on economics. An economics student from a local college was there too. The student began chatting with Ahmad and, once he found that the man before him in kurta-pyjama (he would mostly wear kurta-pyjama when on vacation in India) was the famous economist he had heard of so much, he knelt down to touch his feet.

Syed’s seminal treatise Capital in Economic Theory: Neo-classical, Cambridge and Chaos earned him wide acclaim. Ahmad’s nephew, son-in-law and former Union Minister Dr Shakeel Ahmad says: “Dr Manmohan Singh would often ask me about Syed Ahmad Sahab. He valued his works.”

Besides being a towering scholar in economics, Ahmad was also a passionate lover of Urdu and is credited with preparing Abjadi Loghat Nigari (Numeric Alphabetical Dictionary) in Urdu. A pioneering work this dictionary in four volumes talks about the relationship of Urdu alphabets with numerics.

Before I read the Urdu book Syed Ahmad Aur Abjadi Loghat Nigari (Syed Ahmad and Numeric Alphabetical Dictionary) by Dr Syed Mohammed Hibbanul Haque, I didn’t know that this itself is a science. Those of us who grew up in households where Urdu was an indispensable part we learnt that 786 denotes ‘Bismillah hir rahman nir rahim’ ( In the name of God, merciful and beneficent). This Quranic proclamation is often written on top of the page whenever devout Muslims begin to write anything important like letters, religious documents or just even love letters. So, instead of saying it in so many words, they just put 786, reaffirming the sacred start of the document.

Born in a family of zamindars at Bishanpur in Muzaffarpur (Bihar) in 1930, Ahmad was youngest among five brothers. His father Ahmad Ghafoor was a freedom fighter and also a member of Khilafat Movement, started by Maulana Mohammed Ali Jauhar, his brother Shaukat Ali and led by Mahatma Gandhi, in the1930s. Ghafoor also fought assembly election of 1937 on a Congress ticket and won it at a time when the Muslim League had begun finding traction among a section of Muslims.

A man of fine tastes, Ahmad Ghafoor was a connoisseur of Urdu poetry and even played bridge. “He taught bridge and horse riding to his sons, including Syed Ahmad Sahab,” says Dr Shakeel Ahmad. Dr Shakeel Ahmed’s father Shakoor Ahmad who ntook keen interest in politics, was five-time MLA and also a deputy speaker in Bihar assembly.

Syed Ahmad studied at Jamia school in Delhi, joined Patna Engineering College but gave it up in third year. “I don’t want to spend my life wearing helmet (of a civil engineer) and holding a hammer,” he said and quit. He landed up in Aligarh where Dr Zakir Hussain was heading AMU as its VC. The reason he gave to Zakir Sahab for leaving Patna was interesting. Ghulam Sarwar who later became a famous Urdu journalist and politician in Bihar was among Syed Ahmad’s bosom friends. They had started a movement to protect and promote Urdu and had even organised a successful All-India Mushaira in Patna. Noted Urdu writer Akhtar Aurainvi became a big influence whom Ahmad called his “greatest teacher.”

Syed Ahmad had also begun writing poetry in Urdu and published many essays in Urdu newspapers. “My friend circle in Patna was big and I would not get time to study,” he told Zakir Sahab. “I want to be away from Patna and study at Aligarh.”

“Achcha toh log Aligarh padhne bhi aate hain (Ok, so do people come to Aligarh to study too,” quipped Zakir Sahab. And he allowed young Ahmad admission at AMU from where he did MA in Economics. That proved to be a turning point in his academic career. He went on to London School of Economics for higher education, returned to teach briefly at AMU, taught at Kent, Khartoum and McMaster. The boy from the backwaters of Bihar joined the big league and became among Who’s Who of Economics in the world.

In 1980, Syed Ahmad took a sabbatical from McMaster for a year to work on the Urdu dictionary. Spending countless hours at Patna’s iconic Khuda Bakhsh Library and at his home, the famous economics professor read up tomes in Urdu before he brought out a book on a subject–abjad nigari–that many thought had died long ago.

“He revived this science of numeric alphabetical in Urdu. His is a seminal contribution to the language for which it will remain eternally indebted to him,” says scholar Hibbanul Haque who completed his PhD on Syed Ahmad and his Urdu dictionary.

Syed Ahmad’s two grandsons — Saquib Ahmad and Shehryaar Ahmad — are inheritors of his legacy. The boys have done “Graduation in Arts and Science”, a course Syed Ahmad helped create at McMaster University.

Both the world of economics and Urdu were enriched by Syed Ahmad. They miss him today.

Aisa kahan se laein ke tujhsa kahein jise

(Where will I get someone whom I can compare with you).