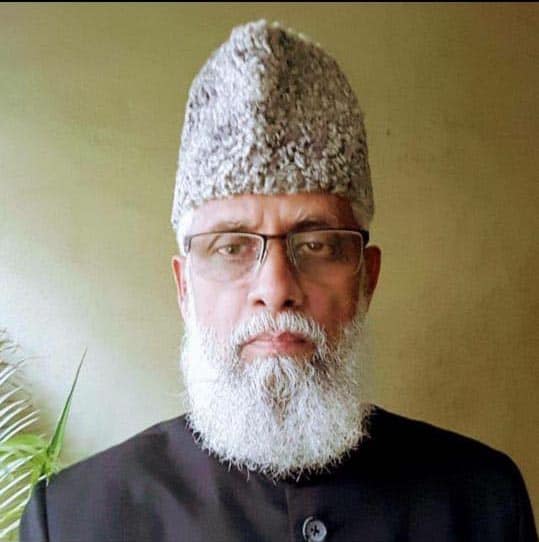

Shafeeq R. Mahajir

An event occurs. The law is violated. Consequences are set down in the statute book. We are, we imagine, governed by law, for perception colours reality. Hence the adage “Justice must not only be done, it must be seen to be done.”

There are policemen charged with apprehending offenders and arraigning them. There are judges charged with trying offenders and sentencing them. An event occurs. The law is violated. Consequences are set down in the statute book.

There are news reports of policemen charged with apprehending offenders and arraigning them not doing so. There are news reports of judges deferring proceedings affording temporal respite and freedom to alleged offenders. There are possibilities of apprehension in the minds of victims of offences that the adage first cited it is not honoured, and possibilities of apprehension that persons charged with implementing the law in the matter of apprehension, arraignment, trial and sentencing, are either less than committed or less than competent. Such news reports and/or apprehensions are ominous signs that do not auger well.

Let us look at some legal provisions. The General Clauses Act defines act such that it includes its counterpart, an omission. To ensure law enforcement officers act judiciously, the Indian Penal Code s.221 declares, “Whoever, being a public servant, legally bound…to apprehend or to keep in confinement any person charged with or liable to be apprehended for an offence, intentionally omits to apprehend such person…shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to…”(term immaterial for our present purposes). What is the culpability of a public servant not discharging duty when required by law to do so?

When an offence is being committed, and one charged with duty of preventing it omits to act, s.107 IPC speaks: A person abets the doing of a thing, who…intentionally aids, by any act or illegal omission, the doing of that thing. So, the one has abetted the offence of the other. Let’s proceed. The matter goes before a judge. Enter s. 77 IPC: Nothing is an offence which is done by a Judge when acting judicially in the exercise of any power which is, or which in good faith he believes to be, given to him by law.

What this means is, even an omission by the judge is not an offence, but note it is not a blanket exoneration: it operates only if he is “acting judicially” and protection is afforded to him only so long as he in good faith believes his action is consistent with power given to him by law. Good faith is defined in sec. 52 IPC: “Nothing is said to be done or believed in “good faith” which is done or believed without due care and attention.” What does this mean? It means there is a deeming provision of absence of good faith whenever something is done without due care and attention. So, the judge will have to establish his good faith. Clear? We paraphrase s.78 IPC: “Nothing which is done in pursuance of, or warranted by judgment or order of a Court if done whilst such judgment or order remains in force, is an offence, notwithstanding the Court may have had no jurisdiction to pass such judgment or order, provided the person doing the act in good faith believes that the Court had such jurisdiction.” See the difference? Even if the Court had no jurisdiction to pass the order, person carrying it out is not guilty of an offence but, as in the previous case, the person will have to establish his belief in good faith that the Court had such jurisdiction. Still clear?

If a judicial proceeding experiences…uh…“improper orders”, s.219 IPC says when “a public servant, corruptly or maliciously makes or pronounces in any stage of a judicial proceeding, any report, order, verdict, or decision which he knows to be contrary to law, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to seven years, or with fine, or with both.” Judges usually know, or ought to know, when their orders can be “contrary to law”.

In 1850, naughty British blighters brought in The Judicial Officers Protection Act. It said “No Judge, Magistrate…or other person acting judicially shall be liable to be sued in any Civil Court for act done or ordered by him in discharge of his judicial duty, whether or not within the limits of his jurisdiction: Provided that he at the time, in good faith, believed himself to have jurisdiction…; and no…person, bound to execute the lawful orders of such Judge…acting judicially shall be liable to be sued in any Civil Court, for the execution of any order, which he would be bound to execute, if within the jurisdiction of the person issuing the same.” Note carefully, protection from civil action alone, subject to the good faith test aforesaid. Note also, not just orders: lawful orders. In 1850, protection was from civil action alone. IPC however, declares thing is not even an offence, which exemption takes it also into the realm of protection from prosecution under criminal law. Still clear?

However, 35 years after we gave ourselves a Constitution, 1985 saw The Judges (Protection) Act which had a s.3 affording “additional protection” to Judges. Sub-sec. (1) reads “Notwithstanding anything contained in any other law for the time being in force…no Court shall entertain or continue any civil or criminal proceeding against any person who is or was a Judge for any act, thing or word committed, done or spoken by him when, or in the course of, acting or purporting to act in the discharge of his official or judicial duty or function.” Sub-sec. (2) allows Central and State Government, Supreme Court, High Court or other authority under law to take action, civil, criminal, or departmental, or otherwise, but you, a citizen cannot, and s.4 tells us this is in addition to, not in derogation of, any other law providing for protection of Judges.

Note, no good faith test. Just an all-embracing protective blanket. Why was this needed in 1985? Did someone in a political party anticipate certain persons holding judicial office could in the foreseeable future possibly pass controversial orders, and be unable to pass the good faith test? How would I know?

That was September 1985. In February 1986, court order opened the gate of Babri Masjid. Before the lock was off, the Judges (Protection) Act was securely in place. Wow! Coincidence? Predetermined? How can I say? However, as lawyers contend, res ipsa loquitur: the thing itself speaks.

A politician raises a slogan goli maaro, someone obligingly fires. A journalist writes a report. Reaction is felt on streets. Instigation? Abetment? I don’t know. Charges framed against politician? Journalist? An offender walks away, someone chooses inaction, omission. Policeman? Can a Judge pass an order when none makes a FIR? Is not making a FIR when required to, not an offence? How would I know? Who is to arraign whom before whom?

I quote Suchitra Vijayan (SV).Words can kill. In 2003 ICTR found Rwandan journalists guilty of genocide, incitement to genocide, conspiracy, and crimes against humanity in a case that raised important questions regarding role of media and social accountability, hate speech prosecuted as war crime. The judgment she notes, declared that the way the journalists had acted constituted “journalism as genocide”.

SV records Charles Mironko’s work confirms hate messages in media had direct effect on dehumanization of population subject to persistent slander, and months of this, in absence of credible reporting, conditioned majority to hate, and kill. Nurembergtrial found Der Stürmer “injected into minds of thousands…poison that caused them to support policy of Jewish persecution and extermination.” Referring to two publications, she notes these were filled with stories of slander, libel, smear campaigns, and fabricated stories, cultivated powerful patrons and moulded their audience into a controllable, incitable mob of puppets.

There is mention of the headline, “Khoon Ka Badla Khoon.” PUCL’s report on 1984 Sikh genocide also reports the same slogan. She cites “trajectory of hate entrepreneurship practiced by some journalists and a section of the media, tracing genealogy from Jabalpur 1961, Aligarh, Ayodhya, Muzaffarnagar, a spate of lynching, and notes the divorcing of ethics from politics, employing mass conditioning and mobilization, to create group hatred, the precondition to riots, lynching, political trials, extrajudicial killings and genocidal violence, legitimisation of collective violence either by state or mob and creation of a dispensable enemy of the state – the “anti-national”, “the secular”, “the minority”. We saw that recently in the matter of Tablighi Jamaat.

Someone, somewhere, charged with the duty of upholding law, is to use the title of Harsh Mander’s book, “Looking away.” Someone, somewhere, vested with suo motu power, “Looking away,” omits to exercise it.

When one has sworn to uphold the Constitution and the Law, has a duty to act, and chooses not to, can one displaying this trait, be described as …traitor to the law?

Res ipsa loquitur.

Shafeeq R. Mahajir is a well-known lawyer based in Hyderabad