Hyderabad: It now remains just the language of poets and dreamers. Time was when Urdu was the medium of instruction for study of medicine. Usually, people jump to the conclusion that it must be Unani medicine. Yes, Urdu is still the language to learn Unani Tib. But not many know that it was also the medium of instruction for study of modern medicine. The credit goes to the Osmania University set up by the seventh Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan.

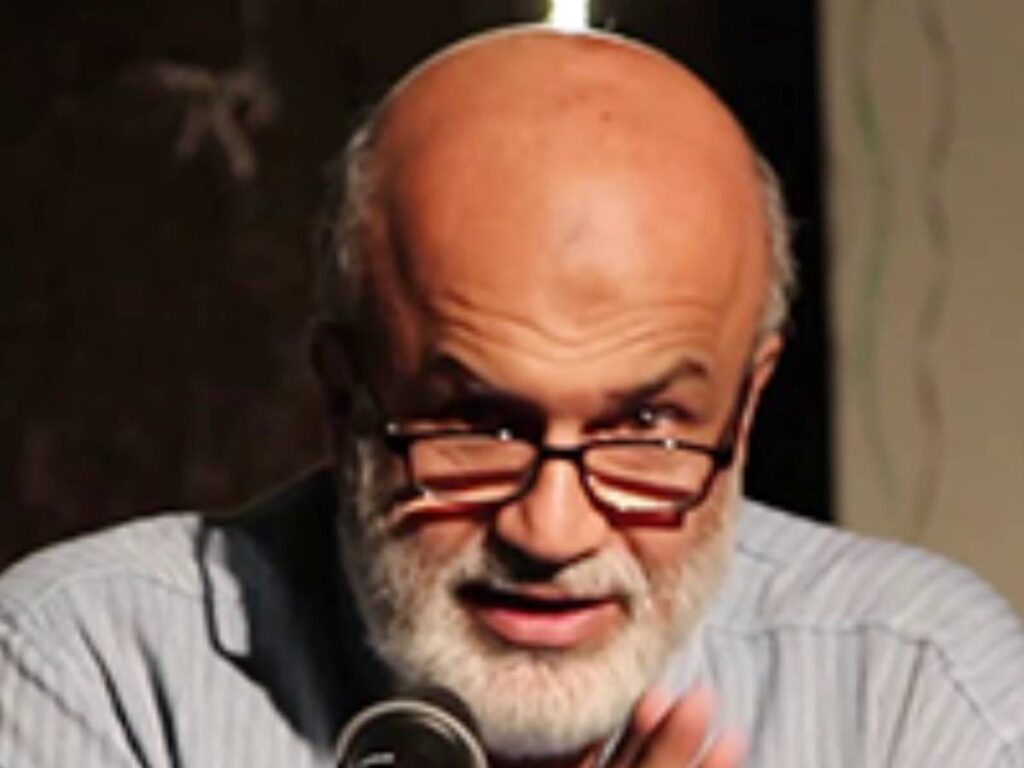

Dr. Abid Moiz’s book Hyderabad Mein Urdu Zaban ke Zariae Jadid Tib’(Modern Medicine Through Urdu Language in Hyderabad) provides a fascinating exploration into the often-overlooked role of Urdu in the study of modern medicine. While many people associate Urdu primarily with poetry and literature, Dr. Moiz highlights its historical significance as a medium of instruction, especially in the field of medicine. He sheds light on the pioneering efforts of Osmania University, established by the Seventh Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan, where Urdu was used to teach modern medical sciences, not just Unani medicine.

The book tells how Urdu played a vital role in bridging modern knowledge with local traditions, ensuring that medical education was accessible to a broader section of society in Hyderabad. This unique aspect of Hyderabad’s academic history challenges the misconception that Urdu is a language confined to artistic expression, revealing its intellectual and practical applications.

A doctor by profession and a writer by passion, Dr. Moiz has authored several books both on science and humour- satire. Earlier, he penned a book titled Jamia Osmania ke Urdu Zaban wo Adab Parvar Doctor. In his latest publication, he meticulously documents the medical heritage of Hyderabad which helps understand Urdu’s cultural and academic importance, particularly in the development of modern medicine in India.

An Osmanian himself, Dr. Moiz expresses a deep sense of regret at having missed the golden era when Urdu was the medium of instruction at Osmania University. Though he pursued his MBBS in English after it replaced Urdu as the medium of education, his connection to the legacy of Urdu remains strong. He looks back with a sense of nostalgia at a time when the university stood as a unique symbol of linguistic and academic fusion, where Urdu, often seen as the language of poets, was at the forefront of imparting knowledge in modern medicine.

His book perhaps reflects that loss, a way of preserving and documenting the rich tradition that he could not experience firsthand. Dr. Moiz’s work not only highlights the history of Urdu’s role in modern education but also conveys his personal sorrow over the shift to English, a move that he feels distanced the language from its practical and intellectual legacy.

Since Urdu was the official language of the Hyderabad state, it transcended religious boundaries, with people from all walks of life speaking and reading it fluently. This deep integration of Urdu into everyday life extended into the medical profession as well. Signboards outside doctors’ clinics proudly displayed their names and qualifications in elegant Urdu script, and patients, upon entering the clinics, were often greeted with Urdu verses and sayings, creating an environment of warmth and familiarity.

What’s more, doctors wrote their prescriptions in Urdu, a practice that reflected the deep-rooted connection between the language and the medical profession. This tradition of using Urdu in such a technical and professional domain highlights its versatility and the prominent role it once played in Hyderabad’s public life.

Through his book Dr. Moiz takes readers on a journey through history, offering a comprehensive account of the Asaf Jahi rulers’ patronage of Urdu and their pioneering efforts in promoting modern medicine through the language. Notably, Urdu was the only Indian language in which medicine was taught before Independence, a remarkable achievement that Dr. Moiz credits to the last Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan, who ensured that the study of modern medicine was accessible in the vernacular.

Dr. Moiz meticulously traces the promotion of modern medicine during the reigns of the last four Nizams—Mir Farqunda Ali Khan Nasir-ud-Daula, Mir Tahniyat Ali Khan Afzal ad-Daula, Mir Mahbub Ali Khan, and Mir Osman Ali Khan. The book carefully documents the progress made under each Nizam, showcasing their vision and dedication to making healthcare education accessible in the region’s native language. Modern medicine was taught in Urdu at Osmania University from 1926 until Hyderabad’s merger with the Indian Union in 1948.

The entry of allopathic medicine into Hyderabad, initially through the British military and missionaries, caught the attention of the fourth Nizam, Mir Farqunda Ali Khan, who was so impressed with this modern line of treatment that he established the Hyderabad Medical School in 1846. This marked the official beginning of imparting modern medicine through the Urdu medium in Hyderabad.

As Dr. Moiz highlights, the establishment of hospitals and dispensaries soon followed, expanding healthcare services in the region. However, the tradition of healthcare in Hyderabad dates back even further, to the time of the city’s founder, Mohammed Quli Qutb Shah, who had set up the Darushifa Hospital for the welfare of his people. This deep-rooted history underscores the rulers’ longstanding commitment to public health and the use of Urdu as a medium of instruction.

A particularly significant aspect of Dr. Moiz’s book is the inclusion of articles written by six doctors who received their medical education in Urdu at Osmania University. Their write-ups offer personal insights into the unique academic environment of the time and stand as testimony to Urdu’s enduring impact in modern medicine. This makes Dr. Moiz’s work not just a historical narrative, but a living memory of a bygone era in Hyderabad’s medical education.

Dr. Abid Moiz’s book provides not only a scholarly account of the role of Urdu in modern medical education but also a glimpse into the unique cultural and social dynamics of the time. Some doctors, like Dr. Syed Kazim Husain, offer a humorous peek into the challenges faced by students due to the absence of co-education in the university. With no female students around, the boys were disappointed, and in their frustration, they turned to poetry to express their feelings. Playfully composing verses, they often directed their poetic expressions at handsome boys, using the art form to channel their emotions. Sample some verses:

Raqsaan hai bijilian teri kafir nigah main

Aaaraz sharab, jis ka rangeen jam hai

Kijiye ab apne shayer khasta par ek nazar

Aashiq hai khush khisal, rangeen kalam hai

These playful expressions reveal the lighthearted and human side of the otherwise rigorous academic environment, adding a personal touch to the historical narrative.

All in all, Dr. Moiz’s book offers an engaging read, blending historical documentation with cultural anecdotes. It is a valuable addition for anyone interested in Urdu, history, and medicine. It surely is a must-have collection for lovers of Urdu.