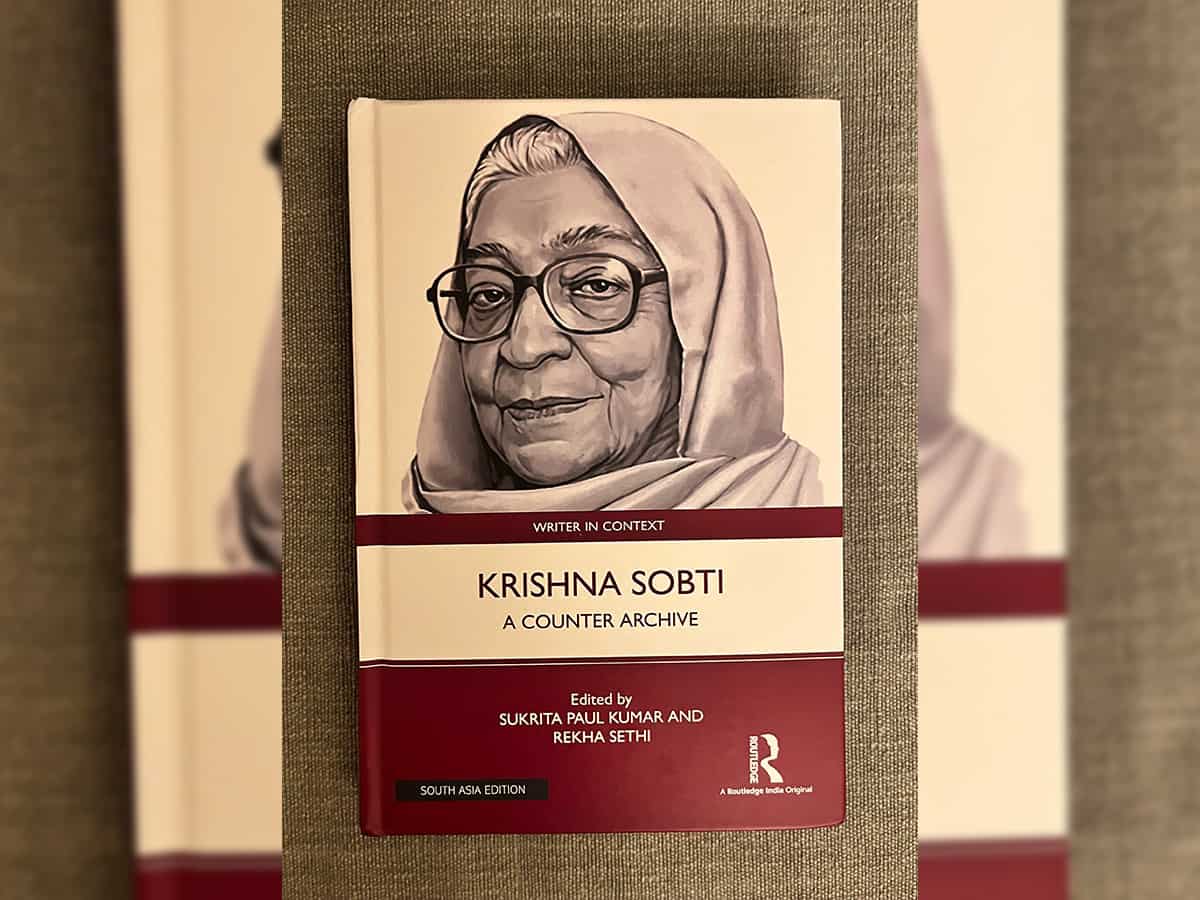

Does the yearning for sensuous pleasure invalidated by the social norms, cultural practices and the canon of public morality denote a means for reconciling with unpredictable, paradoxical and quotidian strands of the human psyche? Do the tantalizing and titillating features of the idiom of female desire upend the unmingled and felicitous use of language? Does the writing preserve the indomitable melody of life in the form of an archive that all can access? Is the creative outpouring referring to something that Jacques Derrida (1930-2004) describes as both a place of commencement and commandment? Is it a means that salvages remain untouched by the vagaries of time? The answer unfailingly, an emphatic yes, cannot elude anymore if one pores over the oeuvre of the nonconformist celebrated Hindi writer and Jnanpith awardee Krishna Sobti (1925-2019). How Sobti upends the dominant narrative by articulating the above-mentioned unsettling questions has been articulated by a well-known poet and critic, Sukrita Paul Kumar and a reputed critic and translator, Rekha Sethi, in the recently published book, Krishna Sobti: A Counter Archive (Routledge,2021).

A marked sense of daredevilry dotted with creative luminosity and invulnerable courage dovetailed into the writings and personality of Krishna Sobti. Her anti-establishment streak manifested when she refused Padma Bhushan. She pursued a case against the iconic figure of Punjabi literature Amrita Pritam (1919-2005) for violating the copyright related to the title of one of her books said to be used by Amrita. She was bold enough to get her 300-page novel destroyed as a reputed publisher reshaped her idiom that juxtaposed Rajasthani, Punjabi Urdu and other colloquial words judiciously.

Seldom does one see the tantalizingly layered Portrayal of promiscuity and sexual overtures of an ordinary middle-class married woman in Hindi fiction that frequently presents their sob stories who reel under patriarchy and virtually have no sexual orientation? Life of desire transcends time and space, and it is what she zeroed in on her umpteen stories. Her life story bears its testimony as she tied the marital knot at seventy.

The title, A Counter Archive, clarifies that it is not a run-of-mill as the contemporary resonance of one of the vibrant polyphonic voices of the Indian literature is made more audible through the fast-changing concept of the archive. Sobti turns attention to desire, enticement, apathy, forgetfulness, hesitation, violence, hatred, history, gender discrimination and seeks to understand the dialectical relationship between archives and the structure of human memory. Derrida delivered a lecture on The Concept of the Archive: A Freudian Impression. He debunked the myth that the archive is usually situated in a privileged space and the authors and new means of communication made it a public space. Inline Derridian concept of the counter archive, the two inventive editors Sukrita and Rekha sought to locate Krishna Sobti and asserted in the introduction: “Krishna Sobti was an embodiment of a counter archive in her writings as much as in her living. Counter archives are disruptive and conventional narratives, and while they tend to engage with the past and historicize differently, there is also a futuristic intent built into them.”

The book, divided into four astutely designed parts, is braced for providing a comprehensive and insightful understanding of the creative impulse of Sobti, who made the body the central motif of female identity. Many of her female protagonists make it a site of resistance and celebration of their sexuality. The first part, Vignettes of the Writer’s Oeuvre, carries facile and occasionally unyieldingly dense translations of several trailblazing novels of Sobti, Mitro Marjani To Hell with you Mitro!) Surajmukhi Andhere Ke (Sunflower of the Dark) and Ai Ladki (Listen Girl!) and part B comprises nonfiction writings of the author. Her widely- discussed novel, To Hell with Mitro, skillfully unmask the layered and intense presence of passion and desire. Mitro’s body is the ultimate means of empowerment, and her frenzied infatuation overruns cultural practices, morality and social norms.

A discerning critic Rekha Sethi aptly argues, “Mitro Marjani created history by presenting a woman character who asserted herself conscious about her body along with projecting her intense sexual urges. This created a tremor in the still waters of the world of Hindi fiction, which had only looked at women through the prism of accepted norms of normality.

Krishna Sobti s magnum opus novel Zindgiinama and Qurrartul ain Hyder’s novel Aag Ka Darya have come in for an insightful debate initiated by the reputed poet and ingenious critic Sukrita Paul. Sobti and Qurraratul evocatively depict shared cultural legacy, and the country’s partition left them embittered. Sukrita sounds convincing. “In both, there is evidence of extraordinary artistic skill and energy at work, in innovating fresh language and style to narrate a history pertinent to the post-partition subcontinent right up to contemporary times. The truths unravelled by the authors of such a range of vision serves as guiding forces in the very living of life in communal togetherness.”

Celebrated poet of new sensibility Savita Singh produced a feminist reading of Sobti’s novel, Listen, Girl! From the standpoint of Indian feminist discourse. Savita insightfully sifted out one sentence that encapsulated the chief constituent of her concept of feminist sensibility, “Ladki, to be yourself is the ultimate, the best.”

The book turns attention to the critical perspectives on Sobti, her conversations, letters. Bio-chronology, and reminiscences of her by several prominent authors, including Ashok the book Vajpai, Girdhar Rathi, Om Thanvi, Vimlesh Mishra, Geeta DharamRajajn. It lives up to its promise of facilitating a comprehensive understanding of one of the mavericks of our times.

Shafey Kidwai is a bilingual critic who got Sahitya Academy Award in 2019 for Urdu. He is professor of Mass Communication at Aligarh Muslim University.