Chennai: “As I was working on agriculture, my family wanted me to take over the management of our plantations. But my aim was to master the art of developing new varieties, that is genetics and breeding. As the proverb has it, we reap what we sow. Consequently, sowing the right things is very important,” M S Swaminathan had once said.

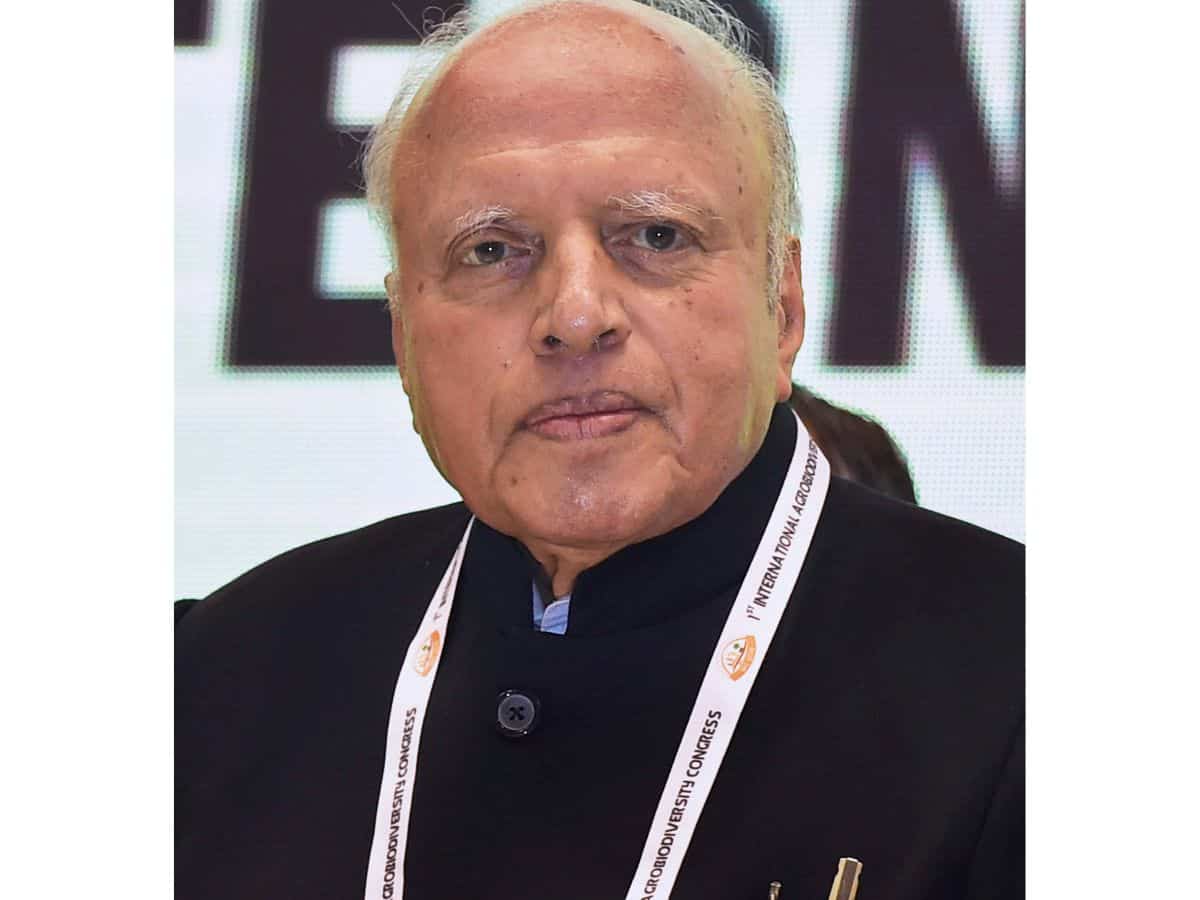

Fondly addressed as MS by his friends and colleagues, Monkombu Sambasivan Swaminathan, in his long career demonstrated what he said and ensured bumper crops by working side by side with farmers.

Born in Kumbakonam in Tamil Nadu on August 7, 1925 to Dr M K Sambasivan and Parvati Thangammai, Swaminathan played a significant role in changing the trajectory of the agriculture sector when farmers were dependent on archaic farming techniques.

Swaminathan belonged to an era when hunger and malnutrition were the order of the day in several parts of the country and the nation, with a population of about 300 million, was on the cusp of independence.

The Bengal famine (1943-44) not only haunted the people but also greatly influenced his career and made him fix his goal on ensuring food security and then nutrition security.

Swaminathan’s research that began as a plant geneticist addressed the issue of food insecurity, helped small farmers increase their income by enhancing productivity.

Eventually, a nation that once depended on American wheat to feed its people in the 1960s was transformed into a foodgrain surplus nation. In recognition of his stellar contributions, he has been awarded Padma Vibushan and numerous other academic awards and honours including the the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award.

In 1968, Indian farmers harvested 17 million tonnes of wheat, in contrast to 12 million tonnes that had been the best in a very good monsoon. The extra five million tonnes was really a quantum leap.

This became the wheat revolution and the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had released a special commemorative stamp in July 1968. Besides wheat, he is also known for his contribution to increasing production of rice and potato.

He dedicated his life to make a turnaround in agrarian economy by employing innovative techniques in agriculture.

He began his research career with cytogenetic studies in potato in 1949 at the Agricultural University, Wageningen, the Netherlands, and later at Cambridge University, where he obtained his Ph D in Genetics in 1952, according to an article in Current Science (Living legends in Indian science).

“Dr Swaminathan used to say that the future belongs to the nation with grains and not guns,” G N Hariharan, executive director of M S Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF), said.

Swaminathan, who established the MSSRF from the proceeds of the first World Food Prize that he received in 1987, was also committed to eliminating the issues of undernutrition and malnutrition, says Hariharan who has been working with the MSSRF for over 29 years.

India, Swaminathan once said that nutrition security involved paying concurrent attention to undernutrition (not eating calories), protein hunger, and hidden hunger arising from inadequate consumption of iron, iodine, zinc, vitamin A, and other micronutrients.

In the 1950s, as a young scientist at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, Swaminathan learned about Dr Norman Borlaug’s newly developed Mexican dwarf wheat variety and invited him to India. The two scientists worked together to develop wheat varieties that would yield higher levels of grain as well as develop stalk structures strong enough to support the increased biomass.

Apart from devising new methods to teach Indian farmers how to effectively increase production by employing a combination of high-yielding wheat varieties and farming techniques, he set up thousands of demonstration and test plots in the northern region of India.

He directly worked with farmers and overcame the problems of illiteracy and lack of formal education of the farmers.

After completing a double bachelors, masters, and Ph.D. in Cytogenetics, he spent two decades in research and administrative positions at agriculture institutes. While India continued to import food grains from abroad, his determination to end the dependence grew.

He was awarded the first World Food Prize for extending the green revolution in India, ensuring food security, and improving the livelihoods of millions.

He received the prestigious Padma Shri, Padma Bhushan, and Padma Vibhushan awards besides receiving 84 honorary doctorate degrees from universities around the world. He was a Rajya Sabha member during 2007-13 and in 2010-13, he chaired the high-level panel of experts for the World Committee on Food Security (CFS).

Through the MSSRF, he impacted various dimensions making a difference to the lives of over six lakh farm families, impacting the livelihood of one lakh farmers and fisherfolk every day with influence spread across 18 countries.

“It gives me great satisfaction to see that India’ destiny has changed from the begging bowl to bread basket and that the government can now engage in international negotiations with greater dignity,” Swaminathan wrote in a book.

Swaminathan passed away here on Thursday at his residence. He is survived by three daughters Soumya Swaminathan, Madhura Swaminathan and Nitya Rao. His wife Mina Swaminathan predeceased him.