The harem culture was common in all royal households in India and it is this very culture that has resulted in succession wars. A common understanding is that the harem and the zenana are one and the same and the terms are most often used interchangeably. The harem was an institution in which as Ruby Lal says gender relations were structured, enforced, and also contested. The harem became over a period of time a bounded space that could be understood as a family. It was a space occupied by royal women and their service class.

The number of women in one’s harem was perceived as one of the major symbols of the state’s power and grandeur. It is here that we see the intertwining of sexuality and power which helps to explore the human expression and social identity of prominent individuals whose interpersonal relationships, physical and psychological well-being were directly associated with the power dynamics of the state.

Harem photographs of the reigns of Mir Mahboob Ali Khan and Mir Osman Ali Khan, the sixth and seventh Nizams of the Hyderabad state, are illustrative of Hyderabad’s pomp and pageantry, splendour and spectacle presenting the zenana as wives, mothers, sisters, as well as cohorts and concubines. Records show routine events like the Nizam visiting the royal women, preparation for marriages, and distribution of gifts.

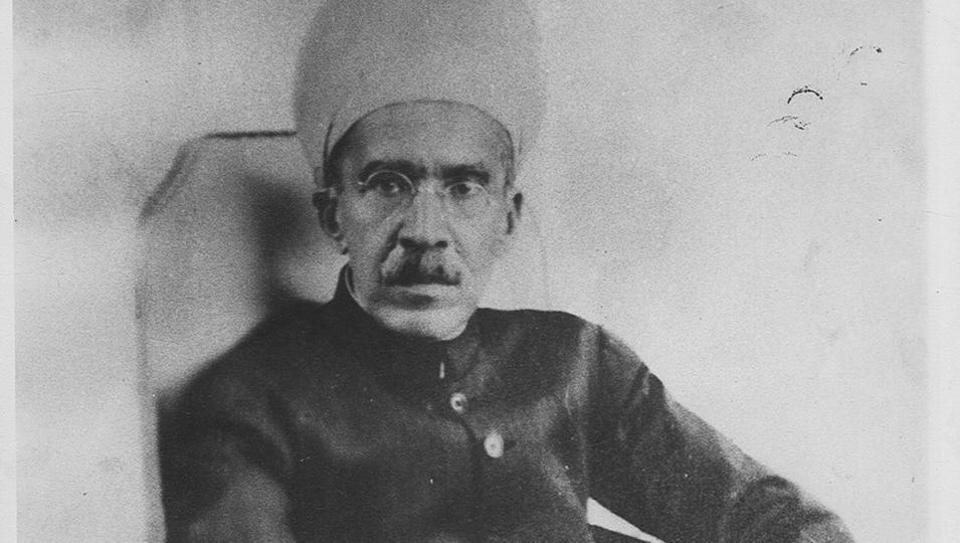

An interesting and well-loved personality of Hyderabad’s regal past was the sixth Nizam Mir Mahboob Ali Khan who ruled from 1884 to 1911. Mahboob was hardly two years old when he succeeded to the masnad under the regency of Nawab Turab Ali Khan, Salar Jung I and Amir-i-Kabir Nawab Rasheeduddin Khan, the head of the Paigah family. Mahboob’s life was short, he was barely in his early forties when he passed away but his life was so eventful that his period is often referred to as the romantic period of Hyderabad.

Some writers have subtly tried to bring out the guarded chapter of Mahboob’s life that was not just a result of his biological promptings but one that operated within the field of power relations. John Zubrzycki in his book The Last Nizam: The Rise and Fall of India’s Greatest Princely State says that Mahboob Ali Khan was barely 16 when he met his successor Osman Ali Khan’s mother, Amat-uz Zehra, who was one among the several hundred women in the zenana. It is believed that she was the granddaughter of the minister Salar Jung I. In The Magnificent Diwan: The Life and Times of Sir Salar Jung I, Bakhtiar Dadabhoy adds to this by saying that she was a Shia Muslim. It is said that the teenage Mahboob had developed an infatuation with a young girl to whom he was writing love letters. When Salar Jung I turned worried at this, the Britisher Captain Clerk suggested that it was time to get the young prince married. But Salar Jung I was not interested in Mahboob marrying any girl from the zenana.

The extent of British intervention in Mahboob’s private affairs is unimaginable and extraordinary when seen in the quantum of measuring complex power relations between the British and Hyderabad. The following details open up private facts of Mahboob’s zenana that have been compulsive and influential.

Caroline Keen’s more detailed analysis in Princely India and the British speaks of a particular meeting in Hyderabad in 1882 between Resident W B Jones and the minister Salar Jung I, where the issue of living quarters was discussed for a possible wife of Mahboob so that he does not get into intimate physical relations with other members of the zenana as was the practice of the royal household. On the flip side, this proposal if implemented would also limit Mahboob’s visits to his mother as this would give him less access to the zenana. Anyway, the British were keen that if the Nizam wanted to marry, any marriage of Mahboob should have the approval of his mother and grandmother.

The British officials in the state wanted Mahboob’s future wife to remain in the Purani Haveli, the official residence of the Nizam, and no women other than those who would attend to her would have access. Salar Jung I resented this as this was against the customs of the zenana and would be insulting to the new bride. Salar Jung I also surmised to the Resident that since the Purani Haveli was the place of stay of the zenana, the Nizam could not be curtailed from accessing the zenana chambers. And of course, he said in no uncertain terms that the British had no right to impose restrictions on the Nizam in his personal life which implied that Mahboob finding opportunities to access the zenana could not be stopped. Such an arrangement of keeping Mahboob away from the zenana would also displease the matrons of the zenana who enjoyed powerful positions. The Resident could not understand and felt that Salar Jung I was acting difficult.

Captain Clerk, who was also Nizam’s tutor, then wrote to the British government of India that Mahboob was keen to solemnise his marriage before he turned 18 as there was a belief if he didn’t marry now he would have to wait for a full one year. Bakhtiar Dadabhoy hits the bull’s eye by calling the British ‘matchmakers’ who were trying to debate whether the girl should be a Hyderabadi nobleman’s daughter or from another Princely State. These considerations were naturally based on political allegiances.

The British were also worried that Mahboob might soon father a child if he married and could also father a child if he didn’t marry. Salar Jung I did not give in to Clerk’s demands as he knew pretty well that if Mahboob married at this young age he would have his own palace which would be independent of the British. Anyway, Mahboob did not marry that young and it was accepted by the British government that the firstborn male whether legitimate or born in the zenana would be recognised as having the first claim to the masnad.

Dadabhoy gives further details of Server ul Mulk, who was later appointed assistant to Clerk, telling the Resident Sir Richard Meade that Salar Jung I was interested in marrying his daughter to the Nizam. Tahniat Yaver-ud-Daula, the Vakil-e-Sultanate had even approached Nizam’s grandmother with this proposal. This would make Salar Jung I more powerful. This is how Amat uz Zehra in whom Mahboob had shown interest was married to him. She was the granddaughter of Salar Jung I through a mutah marriage with a Hindu lady Pritamji. Many books including V K Bawa’s The Last Nizam based on the account of Hosh Bilgrami, the Peshi Secretary of Osman Ali Khan testify that Osman Ali Khan referred to Pritamji as his mother’s munh boli nani.

Caroline Keen says the British expressed a lot of concern about the laxities seen in the zenana which was prevalent for years and Sir David Barr, appointed the Resident in 1900, wanted the eldest son of the Nizam to be recognised as heir and also have a recognised wife with whom he could lead a happy and respectable life which was not known in Hyderabad’s palaces for years. Sir David Barr even goes to the extent of calling the zenana the worst aspect of the Hyderabad palace; the number of women maintained at the cost of His Highness was nearer to 10,000 than 5,000. Living under unsanitary conditions and their manners and customs, according to common reports are altogether shocking and disreputable.

Foster relationships were a common socio-cultural phenomenon that created a dual identity of motherhood i.e., birth mother and foster mother. In Mahboob Ali Khan’s time, when a male child was born there were almost 8 wet nurses chosen for him which had the lurking fear of the infant suffering from over nourishment as Sachidananda Mohanty says in Travel Writing and the Empire. But these practices were not new, the harem has always been a special space, an institution in itself often having separate biological mothers and wet nurses and separate mothers appointed to raise the infants. We see this feature even in the Mughal harem. Look at the other side, the bond created through nursing and raising a child led to a widening of kinship ties with a network of relatives.

The numerous zenana photographs taken by the court photographer of the Nizam, Raja Deen Dayal, during the time of the sixth and seventh Nizams show the celebration of the zenana as an integral part of court culture. Gianna Carotenuto in her thesis on Domesticating the Harem: Reconsidering the Zenana and Representations of Elite Women in Colonial Photography in India talks about “the lavish clothing and the excessive jewellery of the women photographed, each zenana member’s status, hierarchy and influence within the harem, and their relationships to each other and to the Nizam. The range of women who have been portrayed in these pictures emphasize not just the diversity of physical beauty and regional identities of the Nizam’s zenana, but the group photographs indicate the roles and familial associations.” While so many photographs of the Nizam’s zenana show that Nizam commissioned these photographs featuring his wives, children, and concubines and also display them as his possessions.

In the Mysterious Mr Jacob, John Zubrzycki makes a statement about the reason for the death of Mahboob saying Mahboob drank himself to death after a row with one of his many wives in 1911. Narendra Luther seconds this in his book on Raja Deen Dayal: Prince of Photographers that his second wife insisted so much that he appoint her son as the heir apparent that it impacted him to an extent of slipping into a coma. Zubrzycki says that Jacob, the diamond owner who sold the stone to Mahboob, had found the latter “with heavy eyes that betrayed long nights in the zenana and under the effect of opium which he took in doses that would leave most men barely able to function.” Jacob had an extensive network of informants inside India’s royal courts and gathered information ranging from sexual preferences to political policies. Mahboob was after all Jacob’s best customer buying priceless jewels from him.

Rajender Prasad and K S S Seshan also in passing refer to the pleasures of the harem that made it difficult for Mahboob to distinguish between day and night. After attaining the majority, Mahboob remained a popular ruler and despite all the administrative training he had received, his rule was disappointing since it was suspected that the Nizam was involved more in the zenana and had little time left for statecraft.

Davesh Soneji, in Unfinished Gestures: Devadasi, Memory and Modernity gives a reference to Mahboob patronising dance melams from the telugu speaking regions and in The Days of the Beloved, Harriet Ronken Lynton and Mohini Rajan say that Mahboob was used to keeping the transgenders at his palace for days together singing, leaping and dancing. This again isn’t new to history. From ancient times, we see the transgenders guarding the inner chambers of the palaces.

After Salar Jung I’s death, Laiq Ali Salar Jung II became the minister but court intrigues did not allow Mahboob and Laiq Ali to develop a trustworthy bond. Masuma Hasan’s Pakistan in an Age of Turbulence says Mahboob’s reign is eulogized in the Asaf Jahi period. He was to be groomed as a Victorian gentleman but was addicted to drinking and opium and the pleasures of the zenana that held hundreds of women.

This sudden spurt of writings giving stray peeks into the private life of historical personalities like Mahboob Ali Khan form an important component of the power politics of Hyderabad State and gives a new insight into the period. Such writings are also useful in understanding the present complexities of succession that we see today as a result of the power structure and gender relations that were so intertwined in the harems of yesteryears.

Professor Salma Ahmed Farooqui is Director at the H.K.Sherwani Centre for Deccan Studies, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad.