The contentious Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Bill, 2023, was taken up in the Lok Sabha on Thursday, August 3. The INDIA bloc opposed the bill and demand that the government reconsider the move, causing uproar in the House.

Many groups have raised concerns that the proposed bill could clip the wings of the Right To Information (RTI) Act, which makes access to government data a fundamental right.

The bill is seen as an attempt to weaken the authority of the Data Protection Board, which raises further worries. Experts also see a possibility of curtailing citizens’ control over their personal data, which can be misused to target individuals, groups, and communities.

The first draft of Digital Personal Data Protection Bill was framed in November 2022. The Cabinet approved the bill to be tabled on July 5.

What is Personal Data Protection Bill?

The new DPDP Bill is aimed at establishing comprehensive guidelines to ensure an individual has greater control over their information. The Indian government seeks to strengthen data privacy and empower individuals to manage their data.

Data will be collected through data fiduciaries — individuals or entities that process, maintain and secure personal information. They are legally and ethically responsible for personal data security.

The bill will significantly impact India’s trade relations with other countries, especially the European Union, whose General Data Protection law is considered one of the strongest globally.

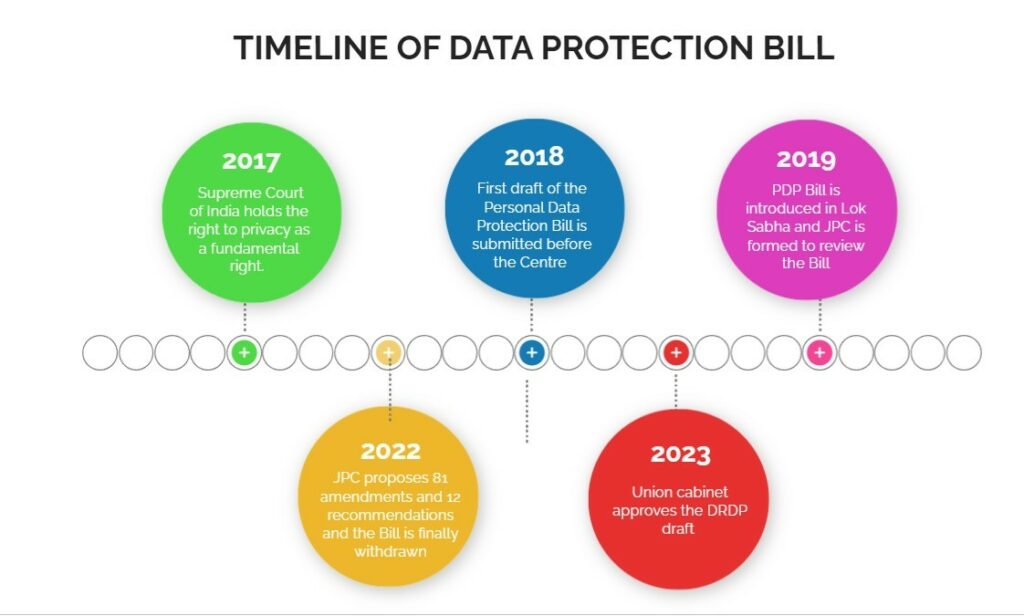

Evolution of the Data Protection Bill

In 2017, the Supreme Court of India included the right to privacy as a fundamental right. In July 2018, a committee headed by retired SC judge BN Srikrishna submited the first draft of the Personal Data Protection Bill to the Narendra Modi-led central government suggesting data fiduciaries. It proposed additional rules for fiduciaries. In this way, the Data Protection Board could handle privacy effectively. In December 2019, the Personal Data Protection Bill is introduced in Lok Sabha and the Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) is formed to review the Bill.

In 2022, JPC proposes 81 amendments and 12 recommendations concluding the bill was more aligned with the Central government than with the interest of the people.

The bill was earlier tabled in the Parliament with Opposition parties expressing strong criticism over ‘non-personal use’ of data under the privacy tagline and gives a free hand to the Centre.

In August 2022, the bill was withdrawn.

Union IT minister Ashiwni Vaishnaw said the government will draft a new version including all recommendations by the JCP.

“After the JCP presented the report, it took us a few months. That was the only time we could have even started on a new draft or think about what to do with it (old draft). Our intent is absolutely crystal clear. What we are doing is basically in line with what the Supreme Court has told us to do,” said Vaishnaw.

“I fully understand that there has been a delay in this, but the subject was too complex. We could have withdrawn it, let’s say, four months back, but we needed a little bit of deliberation before biting the bullet,” he added.

In November 2022, the draft of the bill was released for public consultation.

On July 5 this year, the Union cabinet approved the DRDP draft, 2023.

Concerns surrounding the bill

The new bill is said to have few changes from the previous version thus raising grave concerns regarding data privacy. Here are some of them:

Dependent Data Protection Board: The new bill states that the central government holds the authority to select the members of the Personal Data Protection Board, thus compromising its independence. This way, it can influence the board on which information should be disclosed and which should not, raising apprehensions about its effectiveness in safeguarding data privacy.

Less people-friendly: The new Bill is ‘digital by design’, meaning if a citizen from any financial and educational background needs information, they would have to submit their queries or complaints digitally. In India, where the percentage of internet accessibility is relatively low, this Bill is not people-friendly.

Heavy penalty: If an individual/organisation has access to the internet and needs a piece of certain public-related information, the government can choose to refuse under the ‘breach of privacy’ issue. At this point, the government can levy a heavy monetary penalty upto Rs 500 crore on the individual/organisation.

Effect on RTI: The most important concern is the Bill provides wide exemptions to the central government and its agencies. In the name of ‘national security concerns’, the centre and its agencies can refuse to give data or crucial information. In other words, RTI powers will be diluted.

How it impacts RTI

The Right To Information (RTI) Act was enacted in 2005, granting citizens access to data or information from governments and domains held by public authorities, thus, providing transparency and accountability.

However, under Section 8 (1) (j), the government can refuse to give information provided if the information sought has no relationship to any public activity or has no connection to any public interest, or the information sought is such that it would cause unwarranted invasion of privacy and the information officer is satisfied that there is no larger public interest that justifies disclosure.

The bill will widen the exemptions, giving a free hand to the government and agencies to refuse information. In order words, the RTI’s main functionality of transparency will be subdued.

In this report of The Wire, former central information commissioner Yashovardhan Azad said, “If the proposed Bill is passed, the central and state governments will refuse to give information such as corruption related etc, in the name of ‘privacy issue’.

“If people do not have the right to know what loss happened due to a corrupt action of an official or the government, what is the use then?” The Wire quoted Azad adding, the courts would be the last hope for the right to information.