When the Hindu Sindhis lost Sindh, their ancestral homeland, in the holocaust of partition (1947), they lost more than a piece of land. The sufferers were not just men and women butchered in the bloodlust and families dislocated, but a culture that never recovered from the jolt it received. The Sindhis who were uprooted in the stormy winds that struck the subcontinent in 1947 may have picked up the pieces and the Sindhis today may count among the most prosperous communities on the planet, but the loss of the land has left a permanent scar on their psyche. Yet humans must overcome monumental tragedies, and mindless vivisection of a country they call home. Academic, historian, diligent researcher, and former Principal of the iconic R D National College in Mumbai’s Bandra Subhadra Anand’s novel Tryst with Koki: A Post-Partition Journey of Survival, Sustenance and Strength takes you down memory lane.

There are books on Sindh and Sindhis dime a dozen. But unlike history books or sociological studies, Anand’s own doctoral thesis “National Integration of Sindhis” is a sociological study on the survival and assimilation of the Sindhis in India post-partition, Tryst with Koki captures not just the trauma that the Sindhis faced during partition and its aftermath but also how they rebuilt their lives from a scratch. Through clever use of fiction, Anand tells us also how the Sindhis, through hard work, entrepreneurship, business acumen and with an urge not to survive like refugees eternally, they rebuilt their lives.

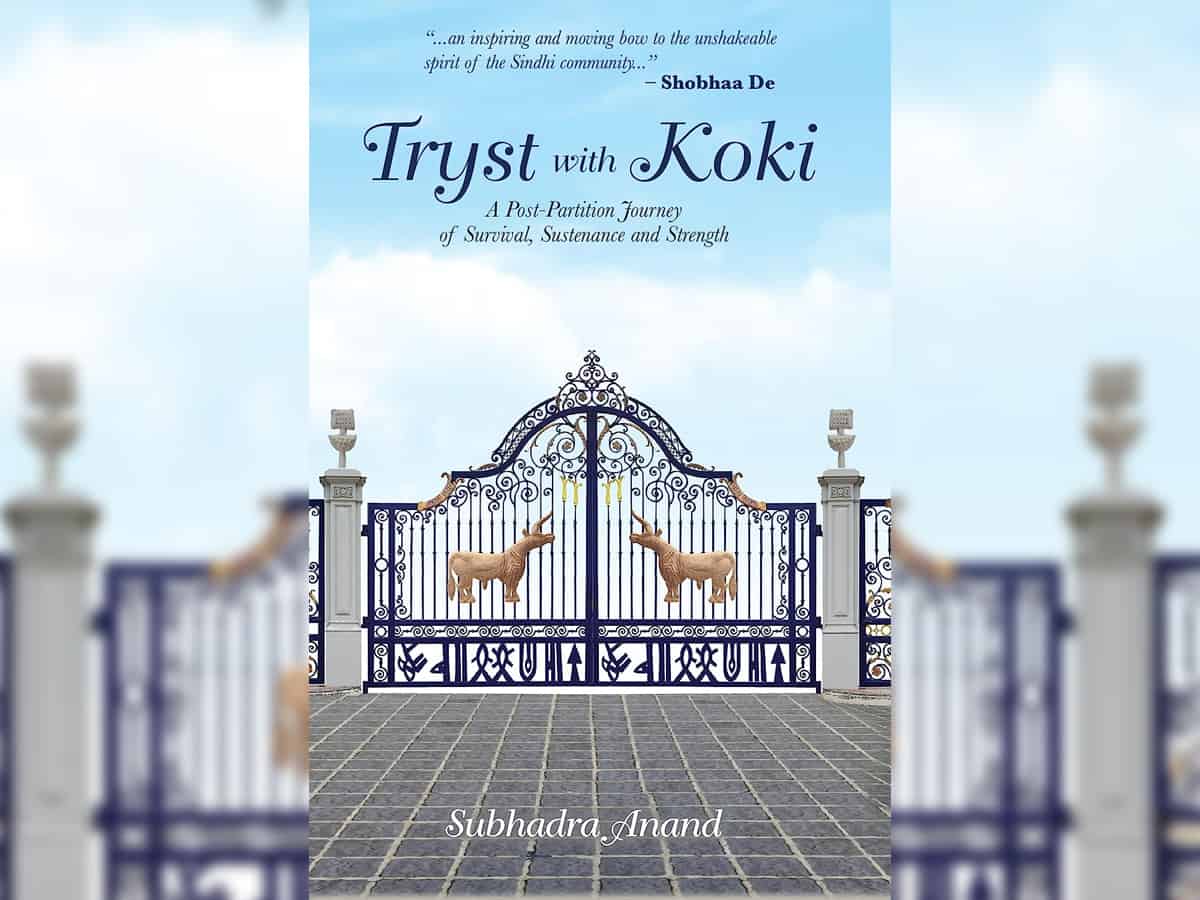

There is a surprise—how many non-Sindhis know what Koki is? —drama, suspense, twists and turns, all the ingredients of good fiction. The Syeds and Advanis are good neighbours in Clifton, Karachi and live in peace and harmony, a Unicorn gate opening paths to the two homes. A few months after partition, Sheila, along with her mother and two siblings, journeyed to a distant and strange land aboard a steamship. They reach Mumbai (then Bombay) and end up at the refugee colony of Ulhasnagar. From the spacious and comfortable house in the tony neighbourhood Clifton in Karachi to the depressed, infrastructure-starved ghetto Ulhasnagar, their fortune’s fall is unfathomable. Yet, Sheila shows a rare grit, and exemplary courage in the face of hardships and obstacles. By the time she turns 75, the family has prospered, with its members becoming part of the global Sindhi diaspora.

But why is the title tryst with Koki? I had heard of and read the famous speech “Tryst with Destiny”, that our first Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru delivered so eloquently on August 15. At lunch on a recent afternoon, I asked Mrs Anand this question. “Koki is a long-lasting Sindhi flatbread. Here it can be seen as a metaphor because it was Koki on which Sheila and her family survived while traveling from Karachi to Bombay. Koki keeps appearing in the novel, from squalid Ulhasnagar to rich and fabulous homes of Sindhis across the world. It symbolises resilience and the powerhouse of energy Sheila had,” explained Mrs Anand. Please give me my Koki.

But hey, I am not going to tell the entire story and rob you of the joy of reading the book from cover to cover. Since the author was born in 1947 and came from Karachi to Bombay on a steamship in 1948, she can easily be called a midnight child who moved with millions and grew up with a feeling that partition stole their land, language, and culture. As a historian who has studied Sindhis’ life, spent countless hours researching their status in squalid hamlets, and interacted with both the poor and the prosperous in her community, Mrs Anand has a thing or two to tell the new generation of Sindhis. This book is a sort of catharsis for her. Writing has a therapeutic impact. She must have felt this wonderful feeling a writer gets after finishing a book, a labour of love.

Though she talks about the trauma that partition carried (she obviously is not saying what the other side suffered as that was beyond the scope of this novel), she does not preach enmity or animosity against those who occupied homes, courtyards, orchards, factories, farms, and gardens vacated by her community members. This message of harmony and human bond is beautifully hammered home through an episode in the tale. Post-Sheila’s death, her niece Sonia, a journalist, reaches Karachi, looking for Salim, Sheila’s neighbour. She hands over half of the unicorn Sheila had kept carefully to Salim. Salim, now old and fragile, brings out the other half of the unicorn and joins them before they together bury them where the gate once stood. Salim also accompanies Sonia to the ancient Indus River to immerse the ashes of Sheila. The readers carry home two strong messages.

Sheila and, by extension, all the Sindhis who were uprooted due to partition, do not harbour animosity against those whose forefathers might have joined the mobs which maimed innocent women and children and looted their properties. Another message is that the Sindhis urge for their homeland even today. This urge is described by the very fact that to fulfill Sheila’s will, her ashes are immersed in the timeless Indus River.

I have known Mrs Anand for over a decade. Much younger than her, I have enjoyed her hospitality, eaten Sindhi delicacies, including Koki, and accompanied her to the great spiritual and cultural centre that is coming up in Kutch, Gujarat. When complete and fully functional, this massive complex will be like the Vatican, Mecca, Kashi, Amritsar for the global Hindu Sindhis. For long Mrs Anand has shared this fascinating dream of a great centre to which Sindhis one day will flock to like moths do to light. Meanwhile, pick up this fascinating book and get immersed in the wonderful story she has spun.