Hyderabad: War, merger, liberation, annexation, take over etc are a bunch of words that different people with differing views on the subject of Operation Polo or Police Action use. The term is denotes the military action that annexed the erstwhile princely state of Hyderabad to India on September 17, 1948.

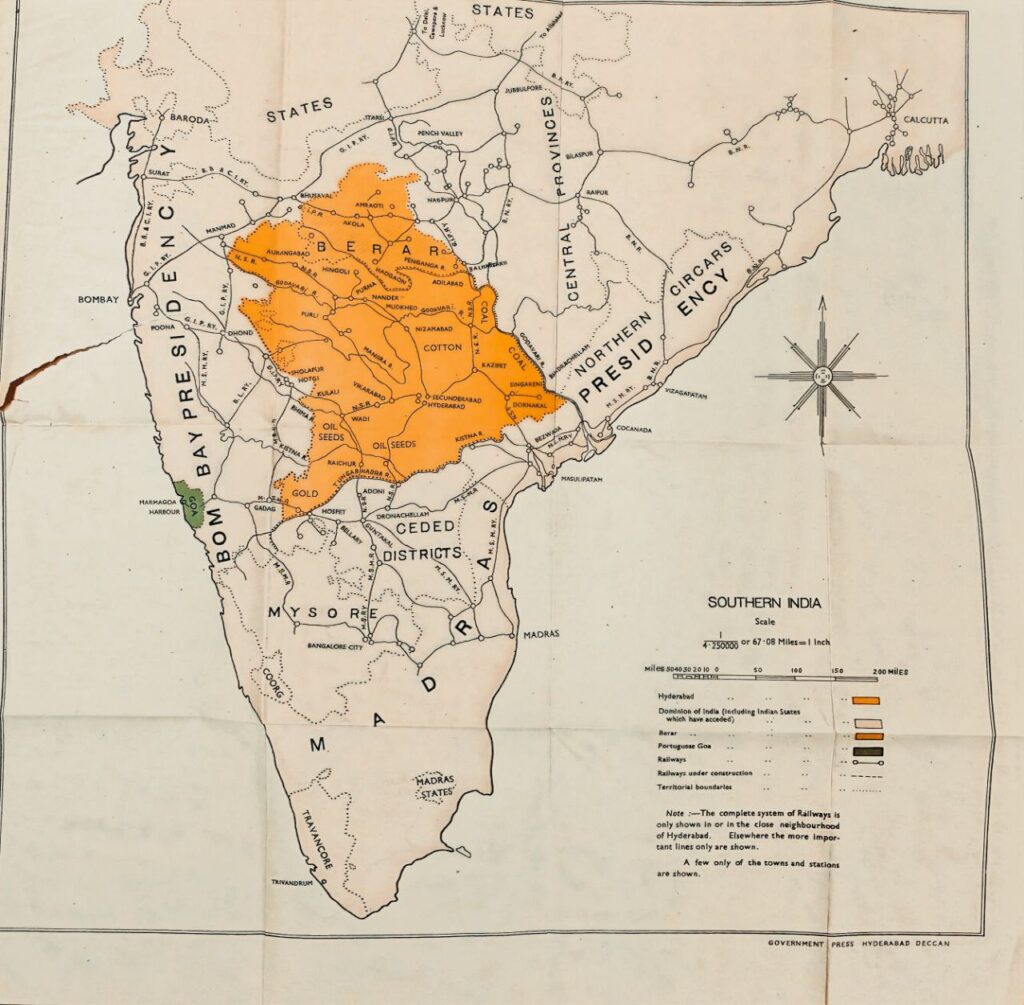

The date is also very important for Telangana, which today is a separate state, but was historically part of the Hyderabad state even well after independence (in 1947) until 1956.

Today, Operation Polo or Police Action has become heavily politicised thanks to a growing right-wing narrative that eventually has led to the Centre observing it as ‘Hyderabad Liberation Day’ – as in liberation from the Muslim ruler – last Nizam of Hyderabad – who the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and right-wing narratives like to call ‘tyrannical’ for various reasons.

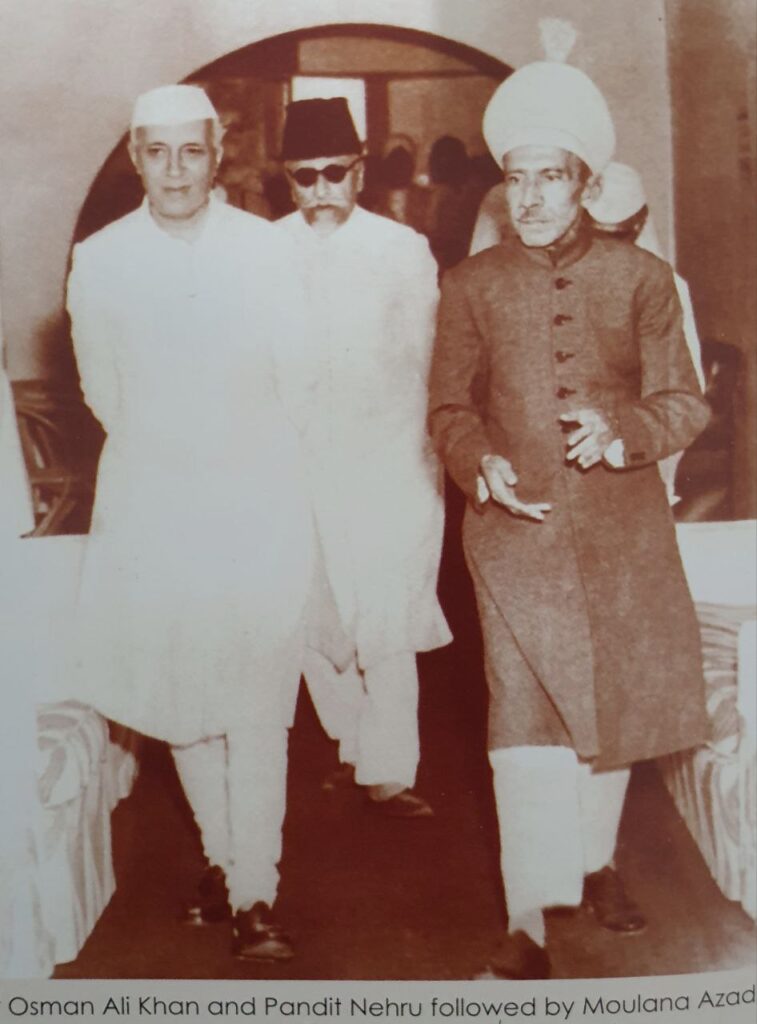

However, even the ruling Congress in Telangana and the previous Bharat Rashtra Samithi (BRS) have today taken a similar tone by calling the Nizam’s monarchy as ‘autocratic’. What is pertinent to note is that prior to independence, all princely states were run by monarchs, and were autocratic and non-democratic by default. Whether the last Nizam of Hyderabad – Osman Ali Khan – was good or bad, or if he took bad decisions, is a different matter.

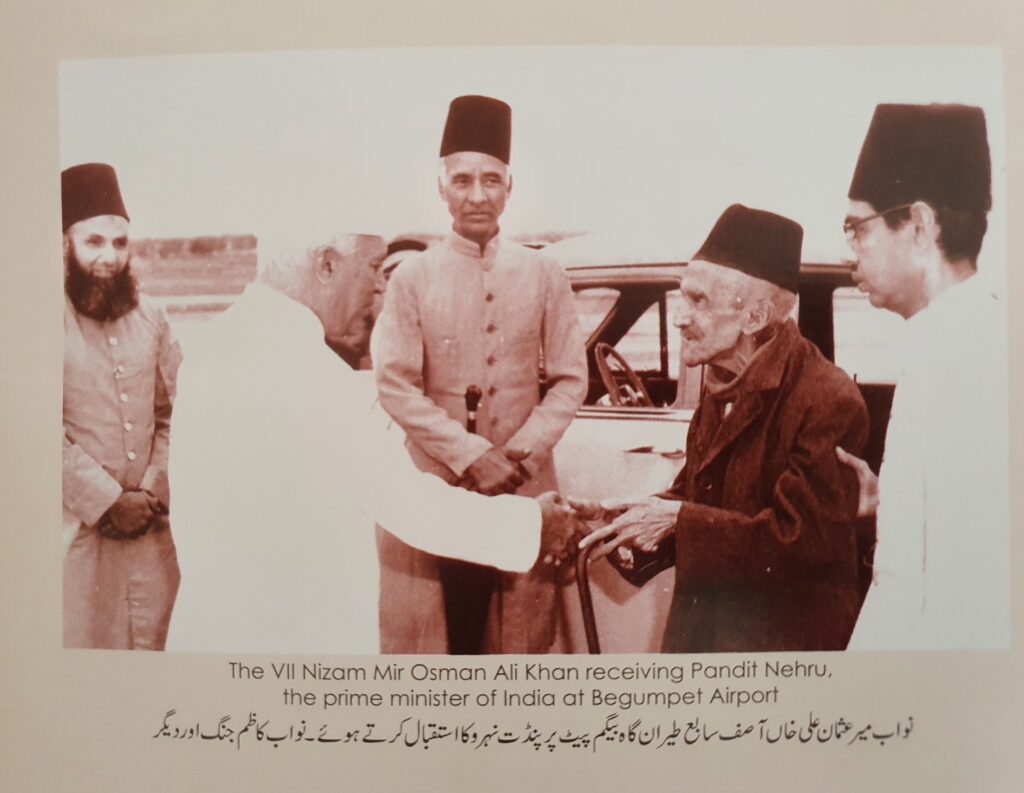

However, beyond political rhetoric, it is very important to take a look and understand the sequence of events that unfolded and eventually led to Operation Polo or the annexation of Hyderabad in 1948. It was anything but an amicable event between the Indian union, then led by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, and the last Nizam of Hyderabad thanks to various factors.

Background of Operation Polo and the Hyderabad state

Run by its last Nizam, the Hyderabad state was the largest one in India. It ran over 82,698 square miles, which included all of Telangana, five districts of Maharashtra and three of Karnataka. It had a population of about 1.6 crore, of which 85% were Hindus and a little over 10% were Muslims (about 43 percent of people lived in the Telangana region).

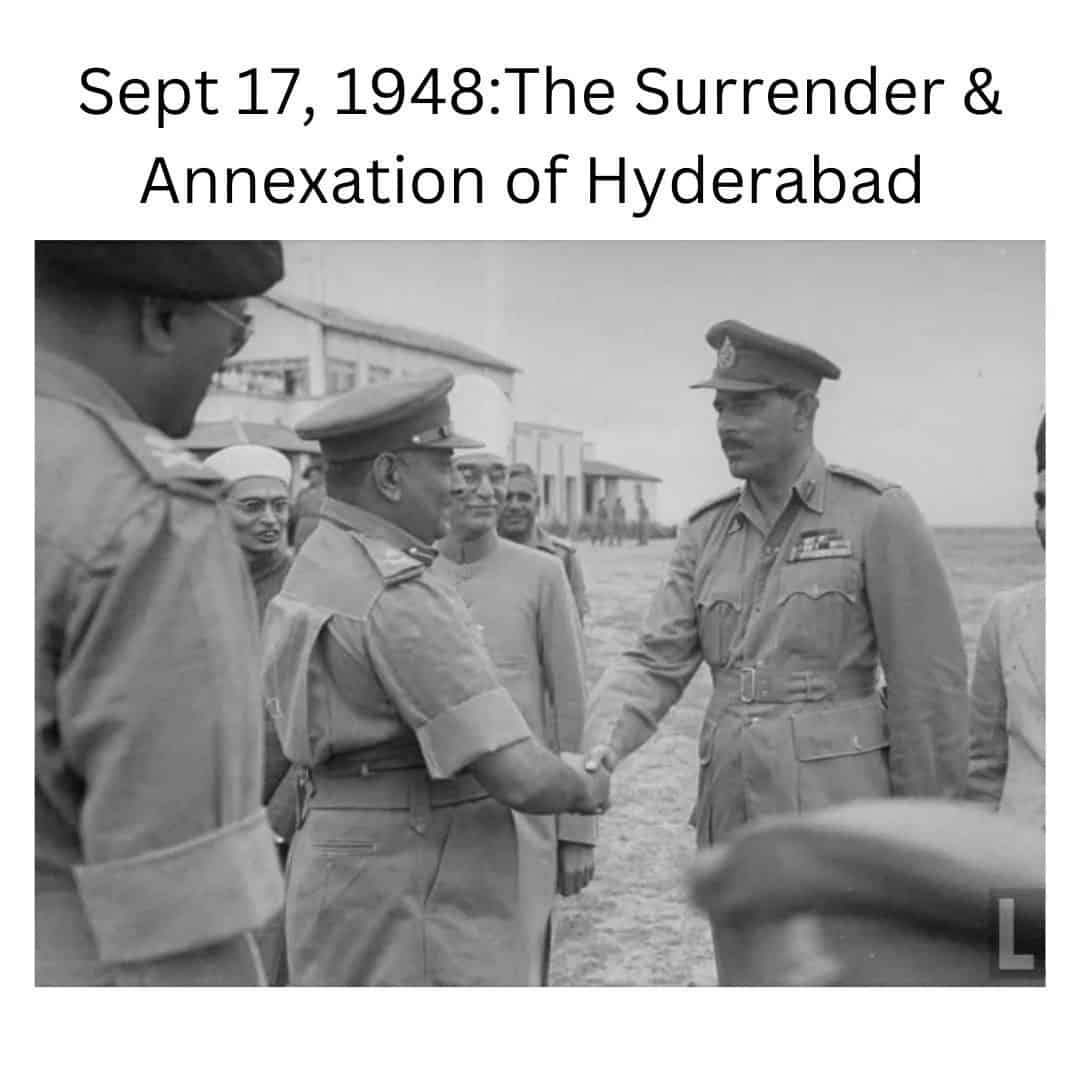

After months of deliberations and talks with Mir Osman Ali Khan failed, the Indian government finally decided to send its army to annexe (or merge, as some call it) the erstwhile princely state of Hyderabad to India with force. Operation Polo formally began on on September 13, 1948 and concluded in about five days on September 17. The Indian union had begun stationing troops well in advance anticipating a fight.

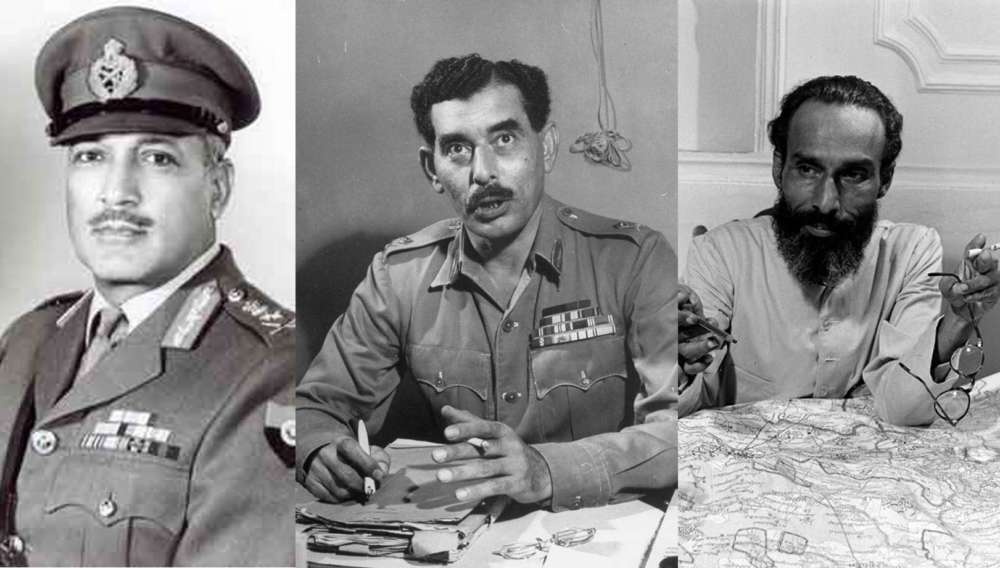

Operation Polo was led by India’s Maj. Gen. JN Chaudhuri. Called Police Action in local parlance, it has left deep scars on the psyche of Muslims even decades later, as thousands had lost their lives in the aftermath. Moreover, another major reason for sending in the army was the Communist Party of India (CPI)-led Telangana Armed Struggle (1946-51).

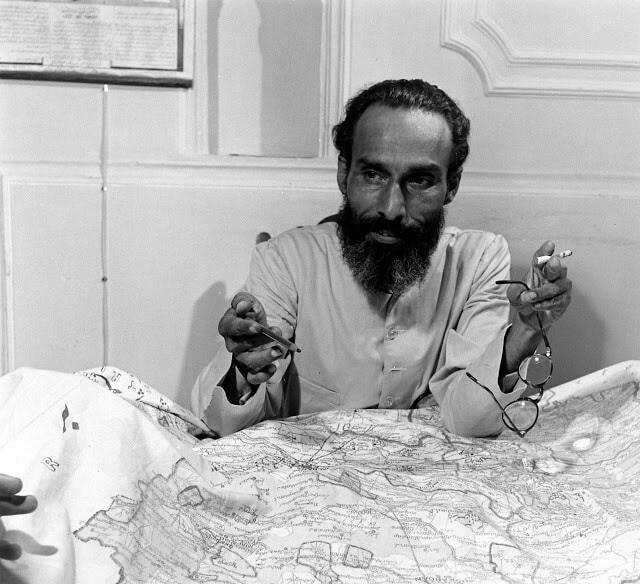

It was essentially a peasant uprising against feudal Jagdirdars (landlords) in the Hyderabad state. It had begun much earlier in 1946. Wary of a communist takeover, the Indian government also wanted to crush the communist movement, which continued till 1951. The CPI called it off on October 21, 1951 and joined the Indian democratic system.

In 1946, a parallel political power vis-a-vis the Nizam emerged in the Hyderabad state, in the form of Syed Qasim Razvi, a lawyer from Latur (Marathwada region in Maharashtra), who took over the reigns of the Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (started in 1927) in 1946 after the death of its former president Bahadur Yar Jung in 1944.

Jung was one the MIM’s most powerful leaders and was a respected figure. It is hard to say what would have happened had he not died under suspicious circumstances (suspected poisoning).

One of the major reasons behind Police Action is believed to be the fanatical Qasim Razvi, who started the Razakar (volunteers) militia, and indulged in atrocities. The issue with Razvi was his violence. The late author Omar Khalidi in his seminal book ‘Hyderabad: After The Fall’ notes that, “Under Razavi’s charge the organisation (MIM) fairly quickly became a militant and somewhat frenzied party, accused, not without cause, of being fascist in both spirit and structure.”

The thing on which the Nizam held onto was the lapse of paramountcy, that the agreements princely states had was with the British. Like Osman Ali Khan and Hyderabad, a handful of other states also insisted that they could choose to be independent, and that they were not bound by rules of the Indian union.

However, one can very easily argue that the princely state of Hyderabad was functioning under the aegis of British India, and that it was never fully independent. The Nizam was supreme in his state, but even he was under and bound to bow down in front of the British monarchy. One can only wonder what the Hyderabad’s Nizam was thinking vis-a-vis Operation Polo, but we will never know because all we have is a curated version of his speech after Operation Polo and the state’s annexation.

Even before India became independent, Osman Ali Khan via a Farman (order) on June 26, 1947, announced his intention to not join India or Pakistan. He also tried to get British Commonwealth status for the Hyderabad state but that was not something Britain was going to entertain. More importantly, the post, telegraph, telephone, railways and other departments that were under the British Indian government in Hyderabad were not in limbo without any clear legal basis, except long established usage.

Moreover, the Indian troops in the Hyderabad state were in a similar position, and the union government was worried about the equipment that was left behind. “Matters regarding currency and trade passports and dealings with foreign powers had to be provided with some new legal basis after the lapse of paramountcy,” writes SN Joshi in The Police Action Against Hyderabad.

The book, written from the Indian union and army’s perspective, also states that matters regarding currency and trade passports and dealings with foreign powers had to be provided with some new legal basis after the British left.

Standstill Agreement between Hyderabad and India

Given that the Nizam of Hyderabad was unwilling to immediately accede to India in 1947, the Indian government, in spite of being averse to it, signed a standstill agreement without full accession as a special case on November 29, 1947. More importantly, this was preceded the Nawab of Chattari, an ex-Prime Minister Hyderabad, getting hounded by Razakars on October 27, 1947, when he tried to reason with the Nizam on the matter.

This, along with the Hyderabad state appointed Laiq Ali as the PM, and a new cabinet on the lines of what MIM chief Qasim Razvi wanted, only made matters worse. Moreover, the Indian government’s agent-general to Hyderabad, KM Munshi, who was sent to liaison with the state, made matters worse as he and Laiq Ali barely agreed on anything when it came to decision making.

While all of this was happening, the Razvi-led Razakaars undoubtedly unleashed violence on the local populace, especially Hindus. This is one aspect that for some reason was largely not spoken of and has been swept under the carpet. While it is equally important to poignantly remember the massacre of Muslims, one cannot also disregard that the people of Telangana in some parts also faced severe Razakar violence.

However, Telangana was better off thanks to the CPI, which began organising peasants and guerilla squads to take violently take back and redistribute lands among farmers. We get an idea of how strong the CPI-led Telangana Armed Struggle was in Edroos’s own book. He writes that the rural areas of Telangana under left-control had a stronger intelligence and that law and order even was in check thanks to them.

Many often forget that the Indian army was stationed in Telangana (Hyderabad state) until 1951 to try and quell the peasant rebellion. The CPI was also fighting with the Razakars until 1948. One of the worst atrocities that many remember is the Bairanpally massacre in which close to 100 people were reportedly murdered.

The Telangana Armed Struggle was however called-off on October 21 by the CPI after which the party took the democratic route and contested elections (through the People’s Democratic Front) in the first elections of 1951-52.

Final days in Hyderabad before Operation Polo

One of the reasons that many believe that set forth Operation Polo was the suspicion that the Nizam was directly or indirectly helping the Razakars. However, this blame perhaps can be put on Laiq Ali, who was more or less doing that. These developments convinced the Indian government that the Nizam was either in league with Qasim Qazvi or was powerless before them.

It was a matter of time before Operation Polo would commence. A militia, and a very legitimate concern that communists would take over the state (they had control of the rural areas) gripped the Indian government. Interestingly, the Nizam sent a secret letter to the Governor general Lord Mountbatten, stating that he would not accede to Pakistan, but also stipulated that he would remain neutral in case of a war between India and Pakistan.

Not clamping down on the Razakars, and a murder on the night of August 22-23, 1948, perhaps changed everything. Burgula Narsing Rao, who was born in 1932, was also the first president of the All Hyderabad Students Union while he was a student at the Nizam College in 1948. A nephew of Burgula Ramakrishna Rao, the first Congress chief minister of the erstwhile Hyderabad State, he was the witness to the murder of a journalist in Hyderabad.

Shoaibullah Khan, a city-based journalist who ran the newspaper Imroze, was shot dead by the Razakars, the intervening night of 22-23 August. Imroze (which was pro Congress then) was run from Rao’s home at Kachiguda. Narsing Rao was also a contemporary of CPI leaders and some of the best statesmen Hyderabad has ever seen like Makhdoom Mohiuddin, Raj Bahadur Gaur, Ravi Narayan Reddy, Arutla Kamala Devi, who all participated in the Telangana Armed Struggle.

While the Hyderabad state tried to tell the Indian government that it was managing fine and that things were under control, the union government however began stationing troops on the borders in early September itself. Laiq Ali and Razvi perhaps assumed that the Indian Army would be busy on the borders with Pakistan and that it would not have much time to spare in Hyderabad.

Sept 13, Operation Polo begins – march to Hyderabad

On September 13, after not willing to wait anymore, the Indian government ordered the army to march in. Hyderabad was no match, this was pretty evident from what Syed Ahmed El-Edroos wrote in his memoirs.

According to Hyderabad of the Seven Loaves by El-Edroos, a Company of Pathan soldiers were the first to receive “the blow” at Naldurg as it did not withdraw in time once the Indian army began marching in to the Hyderabad state. After that another infantry company at Tuljapur in the same area also suffered casualties and that was pretty much the total fight put up by the Hyderabad state army.

The Indian army entered Hyderabad from the Bombay-Hyderabad main road, finally ending Operation Polo. “I realised the hopeless situation which we were in and any clash by our troops with the advancing Indian army would have only led to guilt feelings and probably harder terms of surrender,” wrote Edroos, who was eventually jailed by the Indian government for a few months until an inquiry cleared his name.

According to Edroos, the Razakars had suffered heavy casualties at Bidar where they tried to take on the Indian army. Many fellow men of Qasim Razi reportedly fled and threw away their uniforms in local lakes along with their weapons. The Hyderabad state barely had anyone to fight for it in reality. As many as 3364 Razakaars were captured and 102 were killed.

In the aftermath of Operation Polo, Lt. Col. J. N. Chaudhuri, who led Operation Polo, took over as military governor for 18 months of Hyderabad, after which a provincial government under M. K. Vellodi existed till the first general elections. It may be noted that the last Nizam was made the Rajpramukh in 1950, while Razvi had been arrested and sent to jail for nearly a decade, after which he was allowed to leave for Pakistan.

The Sunderlal committee report formed in the aftermath of Operation Polo states that 26,000 to 40,000 Muslims were killed in communal violence, mainly in the districts of Maharashtra and Karnataka. As far as casualties are concerned with regard to armies of both sides, the Indian Army lost 42 soldiers, while 97 were wounded and 24 missing. For the Hyderabad state army, 490 were killed and 122 were wounded.