Since the world is ever expanding site of unexplained miseries and deep-seated agony, the highest virtue is not to look for divine solace but to document its soul-stirring and multilayered repercussions candidly.

“According to Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996), our biggest social responsibility is to write well and nothing else.”

“Relentless craving for beauty can be the prime concern of life, but it cannot be actualized. Man longs for something that cannot be gratified as beauty always remains elusive and slippery.”

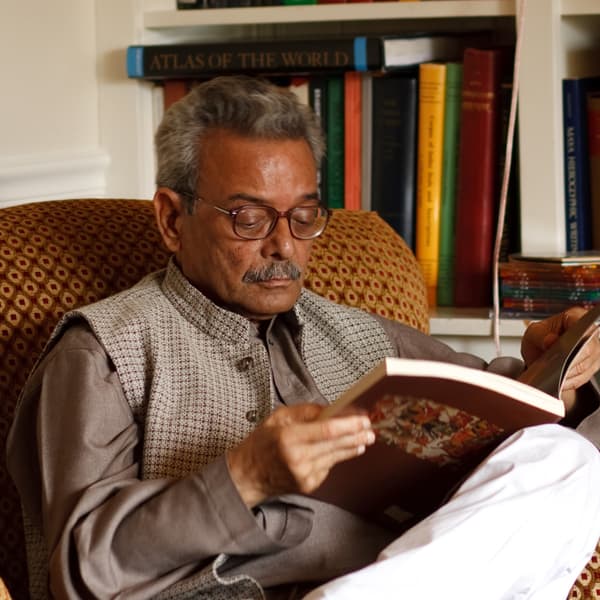

These are the bezels of wisdom uttered by Shamsur Rehman Farooqui (1935-2020) in an incredibly open and insightful conversation with the celebrated Hindi author, poet, and translator Udayan Vajpai eloquently rendered into Urdu by a promising author Rizwan Uddin Farooqui.

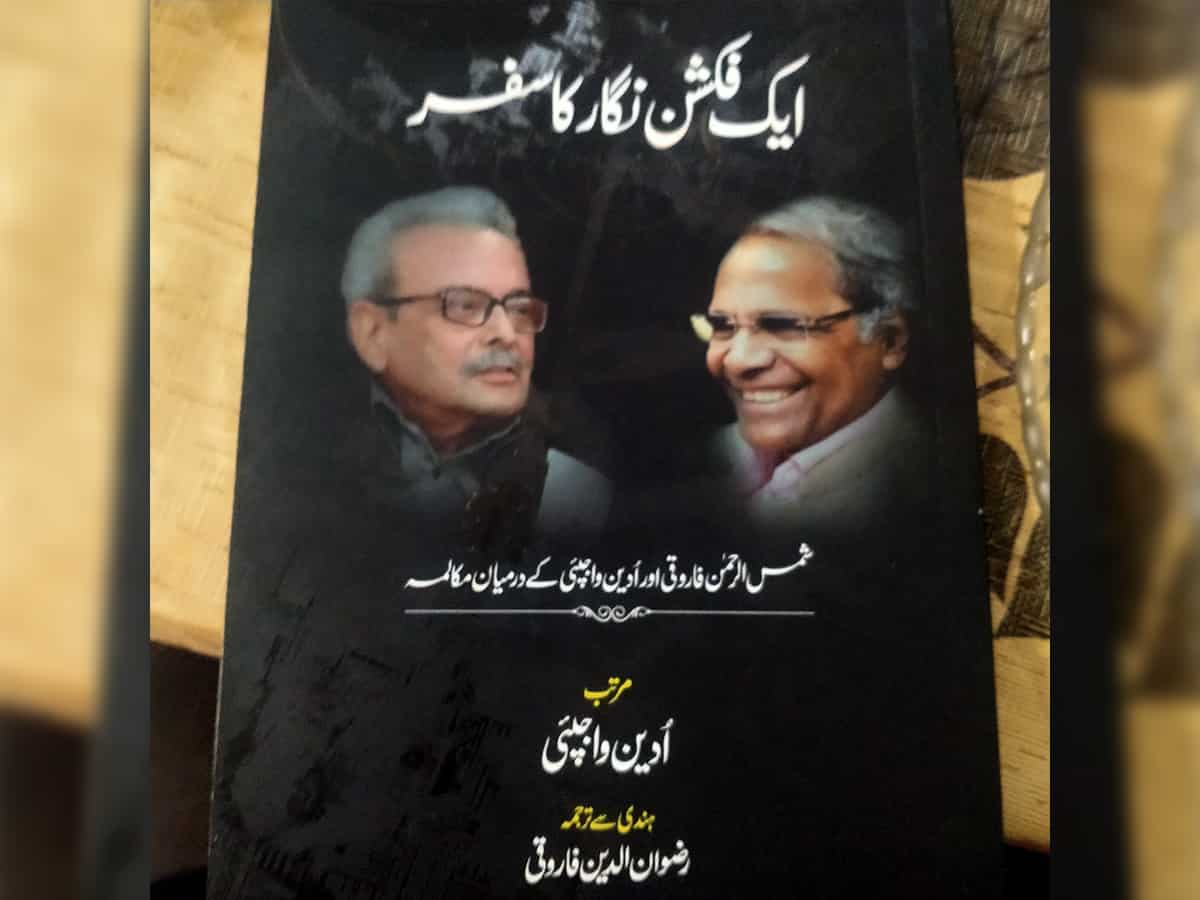

Shamsur Rehman Farooqui, the most influential theorist of poetics and the widely-admired creative and critical voice, hardly got engaged in a candid and down-home tete-a-tete. However, Udayan Vajpai, with his disarmingly unassuming yet orphic literary questioning, unlocked open-ended connections that sum up Farooqui. One can fully understand what it means to be inside and outside the oeuvre of a writer who dominated the literary scene for over a half-century. The interview that goes well beyond the structured question-and-answer format and predictable enumerations first appeared in the special issue of a famous Hindi journal, Samas on Novel, and Ashar Najmi, noted novelist and the editor of a reputed literary journal Esbaat now got its Urdu translation published. Getting to the unconventional, profound, occasionally intricate dialogue with all its nuanced connotations looked quite daunting. However, Rizwan Uddin Farooqui, up to a more considerable extent, did it with a sense of ease as his translation titled, “Aik fiction Nigar Ka Safar: Shamsur Rahman Farooqui aur Udayan Bajpai ke darmayan Makalma,” (Journey of a novelist: Dialogue between Shamsur Rehman Farooqui and Udayan Vajpai) appeared recently.

In an era of linguistic and religious divisionism, Farooqui strove to retrieve Indo-Islamic culture from the effects of colonialism. It was a lived reality and thrived despite the differences though it is now dubbed a composite utopia in some quarters. Denouncing the colonial agenda to highlight the so-called religious specificity of language and culture, Farooqui wrote a voluminous novel, Kaiye Chand the sare Aasman (2006), rendered into English by the author The Mirror of Beauty (2013), vividly tells the tantalizing and occasionally titillating tale of Wazeer Khanam, a courtesan and mother of famous Urdu poet Daagh Dehlvi(1831-1905).

Responding to Udyan’s question about the Novel, he candidly pointed out, “Before jotting down the Novel, I was sure that the Novel would not be about Daagh or his father. Whatever material available on Wazeer Khanam was the second rate which reiterated that each of her sons turned out to be a poet. It means that she was not a woman and resembled the cow whose all offspring turned bull. Instead, it has to be said that she was so talented that no matter who her husband was, she gave birth to all those who composed poetry. It is what Malik Ram wrote. “They were behind the times. Their portrayal of Wazeer Khanan was filled with promiscuity, but I noticed a spark in her character. She represents unblemished beauty that is beyond reach. I constructed a personal history to depict her character graphically.”

Farooqui’s response prompted Udyan to refer to an article on Vladimir Nabokov’s (1899-1977) Lolita(1955) that insightfully points out that the protagonist Humbert wants to conquer beauty and seeks to string along a plethora of girls. He seeks something unobtainable. The very nature of beauty makes it unattainable. It goes well. Farooqui said art always attracts human beings as it has a semblance of life. The quest for beauty remains unfulfilled. People draw sketches of those they long for, but it never happens. Similarly, all draw blank who want to walk off with Wazeer Khanam Either die or are tossed aside by Khanam. At last, she left the Palace.

Farooqui zeroes in on colonialism’s subtle yet pernicious fallout during an informal but insightful conversation. In order to rip up the shared intellectual legacy of Hindus and Muslims, it was vociferously argued that the mentors always put a kibosh on students. It was the myth that gained currency.

Marshalling the contrary documentary pieces of evidence, he mentioned Khwaja Haider Ali Aatish (1778-1847), a disciple of Ghulam Hamdani Mushafi (1751-1824). Mushafi wrote that his disciple Aatish was just 28 years old, but soon he would be a master poet. I admire his poetry and try to emulate him. His seventh and eighth collections of poetry bore testimony to it.

Human existence transcends religious divisions in literature, and Hindu Muslims sync up. Language becomes secondary, prompting Intizar Hussain to describe Kali Das (period 4th-5th century) as an Urdu poet. Farooqui reinforces this by saying that he went through Geeta time and again, as its innumerable translations are available in Urdu. Khawja Dil Mohammad’s translation Dil Ki Geeta was his favourite; though I belonged to a profoundly religious family, there was no restriction on reading sacred texts of Hindus.

Turning attention to novels depicting the unprecedented violence and horrors of the partition, Faooqui regretted that widely mentioned novels such as Train to Pakistan, Peshawar Express, Aur Insaan Mar Gaya, Phool Surkh Hain, and Jab Khet Jage are too mechanical, sketchy, and portrayal of human miseries lacks vision and sensitivity. It looks like some murder machine was used, and the authors had no clue about human suffering. They were acquainting the readers with what was happening. They were not aware of how the victims felt. It is perhaps the first detailed interview in which Farooqui frankly discussed his formative years, his not-too-cordial relations with his teacher and renowned scholar professor S.C Deb (Head, Department of English, Allahabad University) his brief teaching stints at Ballia and Azamgarh before joining the civil service. Udayan Vajpai through his penetrating questioning grounded in academic rigour, brought major literary concerns to Farooqui. One tends to agree with the widely-applauded Urdu fiction writer Khalid Javed who, in his laconic but perceptive preface, pointed out that no interview could vie with this conversation as far as understanding the creative, academic, cultural and ethical concerns of Farooqui is concerned. Rizwan Uddin Faroqui deserves accolades for rendering such a pulsating and engaging conversation between two literary aficionados of our times into chaste Urdu.

Shafey Kidwai, a prominent bilingual critic, is a professor of mass communication at Aligarh Muslim University.