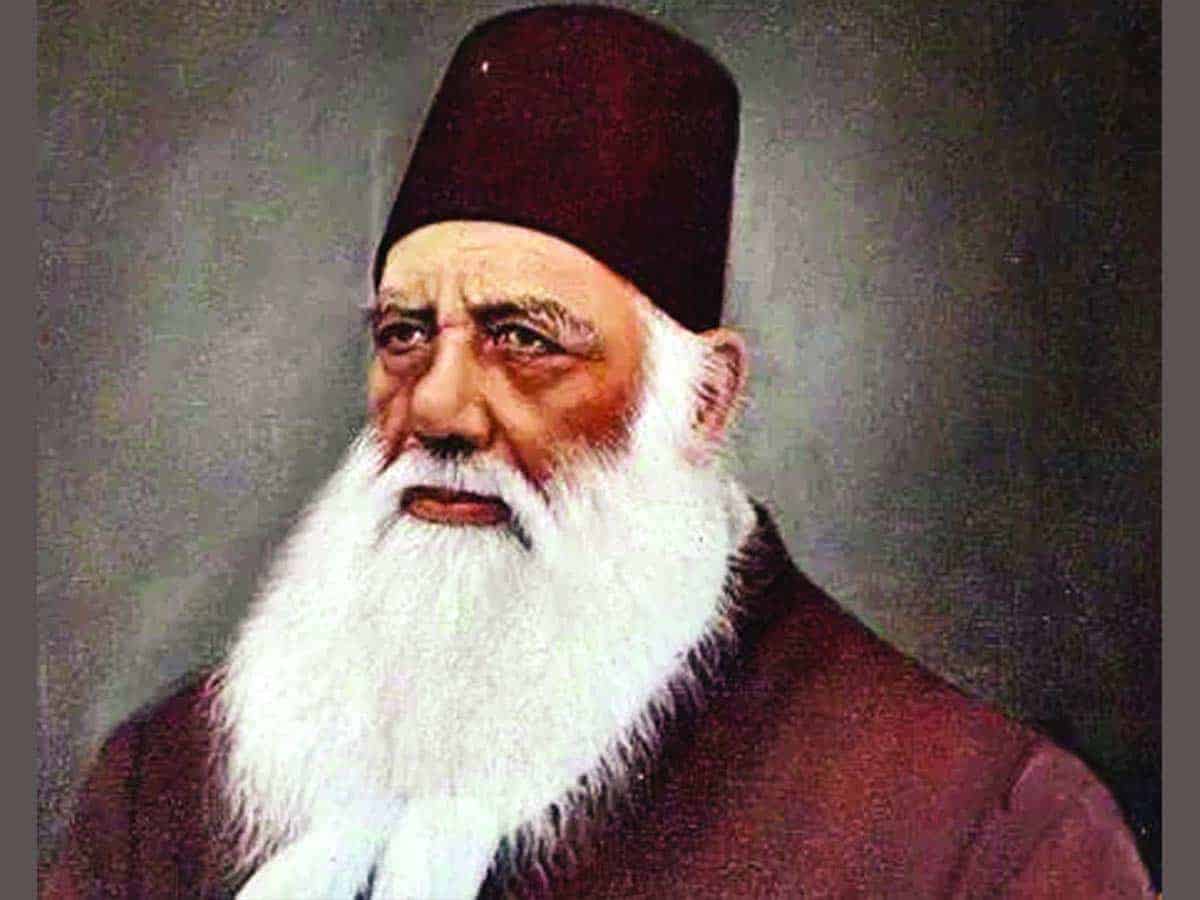

It looks incredible that a person whose vigorous perusal of modern education and breath-taking reforms pulled out Indians from the quagmire of ignorance and subjugation, has explored new opportunities of self-discovery and empowerment through quotidian activity- travelling. It is Sir Syed Ahmad Khan (1817-1898), hardly known beyond being the founder of Aligarh Muslim University. He was essentially a public intellectual and a forerunner of the social, educational, religious and cultural transformation of the Muslims in 19th-century India.

The empowerment of Indians was very dear to him, and all his efforts and struggles were turned towards it. His intent on imparting modern scientific knowledge to his fellow citizens by setting up the scientific society (1864) for translating seminal books into the vernacular, educational institution MAO college (1877), and launching the first multilingual newspaper of the country–The Aligarh Institute Gazette (1866) and Tahzibul Akhlaq (1870) bear testimony to it.

Apart from employing familiar means of mitigating the sufferance of the burnt-up compatriots and putting them on the path of all-round progress, Sir Syed explored the accrued merits of travelling abroad because it is what Ghalib (1797-1869) describes as an act that exposed the begrudging eyes to the breadth of spectacle that excursion produced. Sir Syed’s insistence on travelling reminds us of Aldous Huxley (1894-1963), who puts it, “to travel is to discover that everyone is wrong about the other country”. Travelling was certainly more than an excursion; it produced the epiphany of self-discovery and introspection. Sir Syed’s visit was not meant to strengthen servitude and to legitimize the subjugation, but it was invested with many opportunities that could redeem the beleaguered Indians. He visited London in 1869 and spent 17 months there. His visit proved to be a voyage to modernism, and he realized that if Indians, of course, the affluent ones, could visit England, it would enable them to understand what modern education and western civilization offered them.

For him, it was invested with tremendous opportunities to ameliorate despair-filled collective life and remodel the cataclysmic individual life. Indians believed that travelling across the sea and sharing bread with the Christians would depredate their religion. Discovering the alien land was taken as a religious desecration, and Hindus and Muslims took it in gladly, but this mindset annoyed Sir Syed. He noted with a strong sense of dismay that Hindus living in North, Central and Western India, unlike Bengali Hindus, well-to-do Muslims and Parsis had not broken up the social practice, and they were of the view that religious ritual could hardly adhere to if they made it to England. He jotted down a persuasive editorial, Hindus must undertake the journey to England (Aligarh Institute Gazette, October 29, 1868) and regrets, “till date, only those Bengali aspirants of civil service travelled who do not subscribe to the wrong notion of religious practice and some ambitious Muslims emulated them. However, ordinary Hindus could not muster up the courage to travel abroad and earn their courageous compatriots’ respect. Not a single ritual compatible with true religious postulates could be put on hold, but fictitious practices in pseudo-religious mien could not be carried out smoothly. Adherence to these practices will undoubtedly spell gloom and jeopardize the future. Hindus must shun these practices and make it a point to visit the country of opportunities.”

Sir Syed was equally concerned with the predicaments of Hindus; their sufferings left him exasperated, and when any counter measure enkindled a glimmer of hope, Sir Syed extolled it. If narrow-minded Muslims’ umbrage against Hindus got belied, he felt satisfied. In 1886, nine Hindus from Meerut left for England; Sir Syed wrote a laudatory editorial which reads, “The short-sighted and bigoted Muslims thought that Hindus reeling under stringent caste system and untouchability must be left behind as far as travelling to Europe and studying at Oxford and Cambridge is concerned, but they proved wrong. This month a contingent of nine Hindus, including two women, headed for England. Two North Indian women are cruising for the first time, though Bengali and Parsi females have already made it to London. We applaud our Hindu brethren as they courageously started treading the difficult path. It is significantly more heartening to note that the two women have taken up the arduous task; if they join a medical course and complete the degree or diploma on their return, it will benefit our country enormously.

“Moreover, I predict and congratulate our Hindu brethren that the scholarships for higher education at British institutions will be awarded to them as these are meant for those who pass graduate examinations at the age of 21. We firmly believe that the progress of our country is not dependent on a particular community; the more a community progresses, the more blessed the country will be.” (The Aligarh Institute Gazette, March 27, 1886).

Two residents of Rohtak Lala Ganga Ram and Lala Balmuknd returned India after having passed engineering from England and their excommunication was withdrawn it prompted Sir Syed to write a congratulatory note . Whenever Indians especially Hindus took to traveling abroad, Sir Syed commended it heartily in that he perceived as enriching as empowering as education.