![Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan was a jovial, warm, and humble personality and was known for his wit and sense of romantic renderings.[photo courtesy Wikipedia]](/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/New-Project-4.jpg)

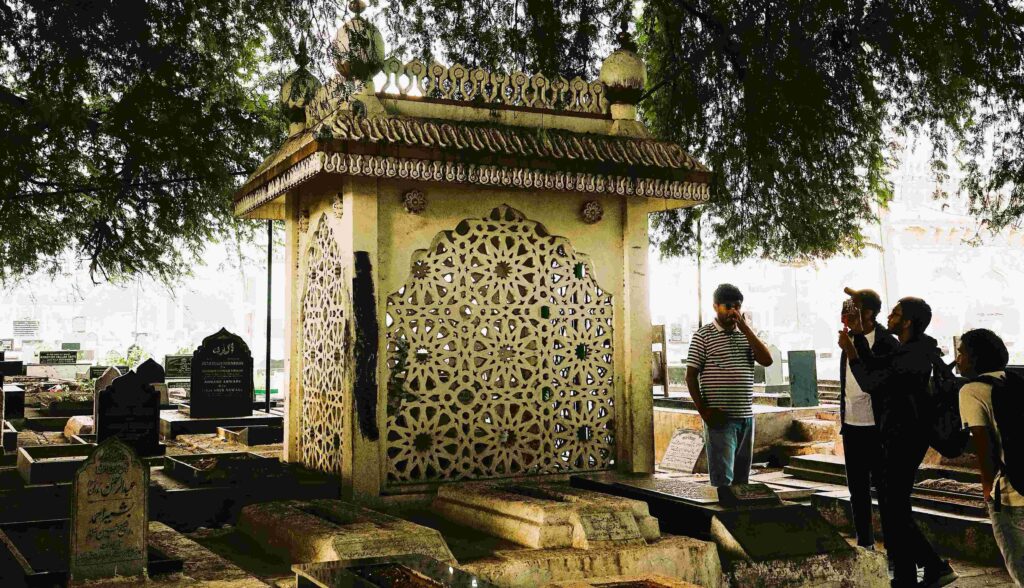

Originally sprawling across nearly 20 acres, the historic Daira-e-Mir Momin at Hari Bowli stands as one of Hyderabad’s oldest cemeteries. This silent sanctuary is more than a resting place; it is a living archive of the city’s rich and reputable past. The sprawling necropolis, with its maze of over 1000 graves in myriad shapes and sizes, holds within its stories of valour, vision, and virtuosity. It is here that some of Hyderabad’s most illustrious figures rest, their lives woven into the city’s cultural and historical fabric.

Among the luminaries who find eternal repose here is Mir Momin Astarabadi, the farsighted planner who laid the foundations of Hyderabad and served as prime minister of the Golconda Sultanate. Mir Alam, an equally influential prime minister whose contributions to the city remain monumental, and three Salar Jungs—successive prime ministers whose legacy still echoes in the corridors of history. Prince Moazzam Jah, son of Nizam Mir Osman Ali Khan. And then there is Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, the unparalleled maestro of Hindustani classical music who loved to enthrall his audiences.

[photo N Shiva Kumar]

One might expect a burial ground of such historical significance to be meticulously preserved, reflecting the grandeur and respect owed to its esteemed occupants. Yet, heartbreakingly, the Daira-e-Mir Momin languishes in neglect. Its ancient charm and profound historical value are overshadowed by apathy. Many graves, once markers of pride and reverence, are now shrouded in decay, their inscriptions fading into obscurity. It must be preserved as a testament to Hyderabad’s heritage.

Modest enclosure

During a heritage walk conducted recently, I found myself fascinated by a small, latticed-designed enclosed tombstone nestled amid the vast expanse of this necropolis. This modest enclosure houses the remains of Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, a voice that transcended human expression and touched the divine. The younger generation may not fully appreciate this legendary artist, but for those who experienced his music, his name evokes reverence. Not to be confused with Ghulam Ali, a prominent Pakistani ghazal singer, who was a disciple of Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan.

Born in 1902 in Kasur, Punjab (now in Pakistan), Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan’s life is a testament to the transformative power of art and resilience. From humble beginnings to becoming the “Tansen of the 20th century,” he redefined the essence of musical divinity.

Young prodigy

[Screen grab by N.Shiva Kumar]

As a young prodigy, Bade Ghulam exhibited an extraordinary aptitude for ragas, mastering their intricate nuances and poignant depths. His early training on the sarangi, an instrument he adored for its vocal-like resonance, profoundly influenced his musical style. “Can you find another instrument so close to the human voice?” he often mused, highlighting its impact on his unmatched taans and gamakas. While gamaka lends unique beauty to ragas with its nuanced twists and turns, taan involves rapid sequences of notes that breathe life into compositions.

The maestro’s public debut occurred in the early 1920s at a Delhi durbar held in honour of the Prince of Wales. However, it was his performances at the All-India Music Conference in Kolkata (1939) and the Vikramaditya Sangeet Parishad in Mumbai (1944) that catapulted him to national prominence. Critics and connoisseurs alike were spellbound by his virtuosic renditions. His voice—a harmonious blend of sweetness, depth, and dexterity—could effortlessly navigate unpredictable swara combinations and deliver taans at incredible speed.

Partition woes

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan’s life, however, was not without challenges. The Partition of India in 1947 uprooted him from his birthplace, forcing him to move to Pakistan. However, the cultural atmosphere there proved stifling, and he longed to return to India. His wish was fulfilled through the efforts of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who enabled his citizenship. Settling in India, the maestro became a beloved figure in its cultural tapestry, gracing countless performances with his divine voice.

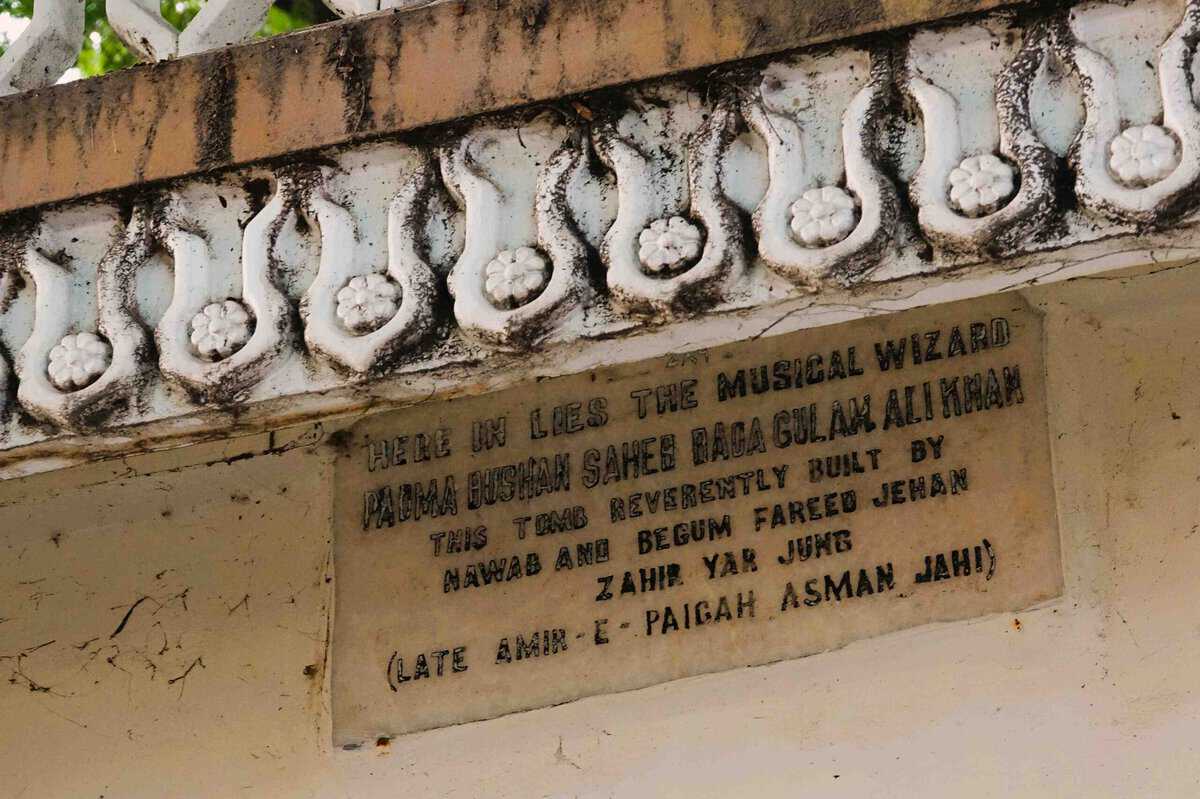

Known for his versatility, Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan excelled in khayals [romantic renderings], thumris, bhajans, ghazals, and even folk songs. His ability to seamlessly blend technical brilliance with emotive expression earned him widespread acclaim. While some critics accused him of “compromising tradition” by shortening the slow sections of ragas or adapting to contemporary audiences, he dismissed these concerns with characteristic candour. “Gone are the days of leisurely durbar concerts that lasted hours. We now sing for people whose leisure is limited and must align our music to their moods,” he said. This adaptability endeared him to diverse audiences, earning praise from the Press, who called him a “musical wizard.” Historian Ramachandra Guha, attributes his work as “a glorious tribute to the cultural mosaic of Indian civilization.”

Mughal-e-Azam

By the 1950s, Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan was a national treasure. The Indian film industry also sought his genius, and his rendition of “Prem Jogan Ban Ke” in Mughal-e-Azam (1960) remains iconic, immortalizing his voice for generations. In his later years, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan settled in Hyderabad, a city he cherished for its cultural vibrancy. He stayed at Basheer Bagh Palace, where he spent his final days. He died on April 23, 1968, at the age of 66, and was laid to rest in the historic Daira-e-Mir Momin.

The Indian government bestowed upon him Padma Bhushan (1962) and a Postage Stamp (1975). Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan’s legacy is more than a collection of exquisite performances. It is a reminder of music’s timeless ability to bridge divides—geographical, religious, cultural, and emotional. His voice, often described as “musical divinity,” resonates as a beacon of artistic brilliance, ensuring his eternal place in the hearts of those who care to listen.