By R. Umamaheshwari

The entry point, in the present case, was a chance recent discovery, on the internet, of a couple of teasers; yet another Ramayana. This film, Ramayan, is expected to hit the theatres sometime in the unpredictable future. It is touted to be one of the most expensive ones yet (estimated $100 million / approximately Rs. 835 crores), directed by Nitesh Tiwari (last in news over allegations that his film Bawaal ‘trivialised’ the Jewish holocaust). The film promises use of state of the art VFX (in excess).

The film stars Ranbir Kapoor as Rama, Sai Pallavi as Sita, and Yash as Ravana. There were reports early on that Vijay Sethupathy would essay Vibhishana’s role, but it appears he may not (thankfully) be part of it. Sunny Deol will play Hanuman. If Lara Datta recently appeared in a video supporting Narendra Modi, no need to be surprised, because she also has a role in this magnum opus.

This is not merely about the film Ramayan and some actors, but about yet another (if we took into cognisance the nature of spread of Vedic Brahmanism in the ancient past) cultural-hegemonic turn in Indian history and politics. Since these films are also an economic enterprise, earning millions of dollars, besides having massive influence on the cultural psyche, we need to ask questions.

The Sangh Parivar’s universalised, mono-Hindu religion (Vedic), fitting into the economic cartography seamlessly, forgets that Sanskritic Hinduism is not practised in every village in India, which has other intimate, everyday expressions (even without the Brahmin priest) and god-concepts (including worship of nature, animism, shamanism and divination), but for the Sangh Parivar’s idea of Hindu Rashtra to survive, the road and other networks, including the Parvatmala idea (which, besides being a commercial project, has a religious context to it), aim to convert these expressions and diverse cultural histories (rooted in a space far removed from the mainstream) into a singular vision and forced unified construct, just as in the ancient times, which also led to the entrenchment of the caste system across regions. These must be located within the paradigm of an economic-cultural-religious complex. And thus, every now and then, you have a serial, or film, such as Tiwari’s Ramayan, for the moment. We do not know yet, if this is based on Valmiki’s original epic, or if it also incorporates the various linguistic versions (within their own cultural contexts) or, if it based on Tulsidas’ Ramcharitmanas.

Coming to the actors, based purely on the teaser trailers. I will focus on two of them. Sai Pallavi poured life into her Malar teacher role in her very first film, Premam (2015), a Malayalam original remade into Telugu. In Telugu cinema, her rise was swift and steady, even as she essayed characters speaking the Telangana language (yaasa) with flair.

Her brilliant performances include that of a strong-headed rural Telangana woman in Fida (2017); an aspiring dancer in Love Story (2021, essentially addressing caste violence, but unfortunately overwhelmed by her dance to Saaranga dariya) and; that of Sarala of Warangal who joined the Naxalite movement in the 1990s (as Vennela) in the film, Virataparvam (2022). People believed that if Sai Pallavi chose a film, it was bound to have a strong woman at the core. She led every film on her own to box office success.

And now, you see a totally unrecognisable Sai Pallavi in the Ramayan teaser: a sufficiently whitened, docile-looking, peaches-and-cream complexioned Sita. It’s sure a letdown. For, she had shared (in the past) her own victory over her self-image, to finally being happy in her own skin (her rare skin condition). The south Indian film industry accepted her as she was. She had, in fact, declined crores, refusing to endorse a fairness cream. She was an actor rooted in an organic cinematic language peculiar to south India, with her wavy hair and every person’s woman image. And now you find almost an AI version of Sai Pallavi in Ramayan.

Actors, of course, have agency (perhaps still) to essay roles they like. Money has a huge role to play in it, too. But it does surprise one that an actor of her calibre and informed opinion should also join this cultural-political project. Because, not long ago, Sai Pallavi found herself targeted by right-wing trolls and activists after an interview she gave to a Telugu TV channel (June 2022) wherein she stated that Kashmir Files showed the killing of Kashmiri pundits, but, at the same time, during the pandemic, a vehicle carrying a cow was stopped, the Muslim driver was lynched amidst sloganeering of ‘Jai Shri Ram.’ She wondered as to what the difference was between these two kinds of violence.

The intense backlash forced her to put out her video clarifying, thus: “I would never belittle a tragedy like the genocide [as she calls the Kashmiri Pandit issue]…I can never come to terms with mob lynching incident that had taken place during Covid times… I believe that violence in any form is wrong and violence in the name of any religion is a huge sin…It was disturbing to see many…justifying the mob lynching. I do not think any of us has the right to take another person’s life…I hope a day doesn’t come when a child is born and he or she is scared of his or her identity. I pray that it is not heading towards that…”

What a long way, to Ramayan, seemingly innocent (?) of its political meaning in the current volatile context.

Coming to Ranbir Kapoor. Again, we see him in Ramayan as an extremely fair-skinned, six-pack-ab Rama. Valmiki’s Rama was darker, gentler, soft-spoken, self-sacrificing, and a morally just hero. The iconography of a macho, warrior Rama became popular from the 1990s (in the backdrop of the Babri masjid demolition) and that is the Rama this film chooses. Looking back at Ranbir Kapoor’s filmography, his understated brilliance came to light in the films Luck By Chance (2008), Wake up Sid (2008), Rocket Singh, Salesman of the Year (2009), Rockstar (2011), Tamasha (2015), Barfi (2012), among others.

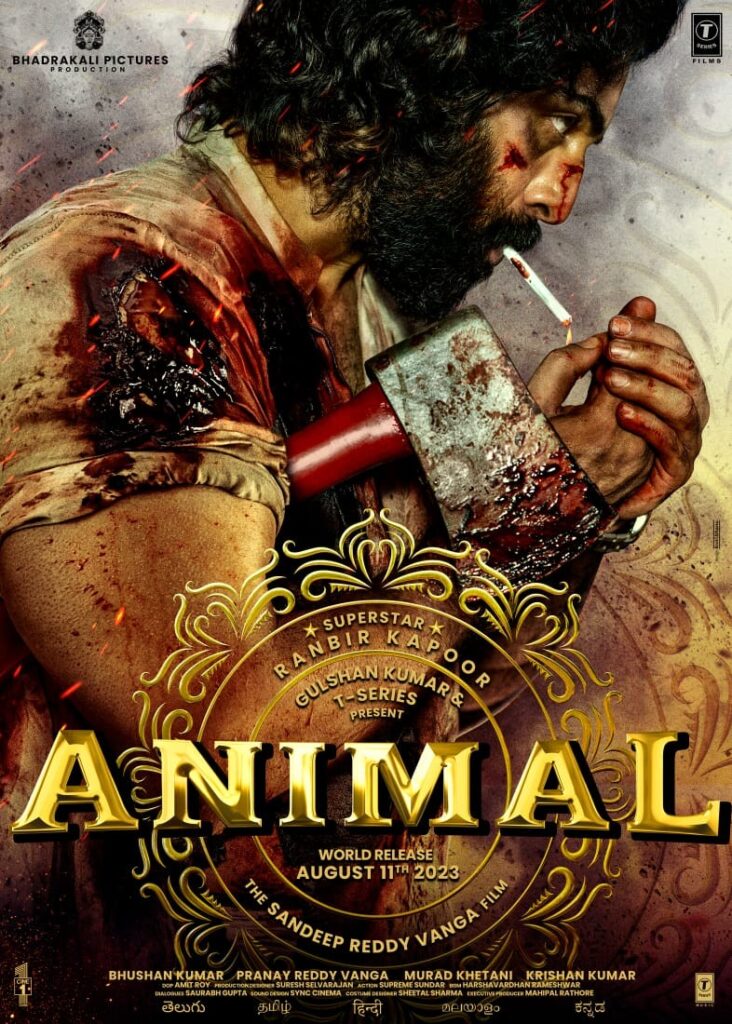

Each of these was of non-confirming, vulnerable, non-macho, angst-driven men. In many interviews, he prided himself for his choices. And lo! Suddenly, he is a pathological, narcissistic, ultra-violent male in Animal (2023). Ironically, it catapulted him to such fame (and endorsements) that, before we knew it, he got an invite to the Ram temple inauguration with wife Alia Bhatt. The role of Rama, then, seems more than mere coincidence.

Finally, the question arises, as to how many times should we make and remake Ramayana and Mahabharata, in a nation of multiple religious traditions and folklore of several communities – Islamic, Christian, Buddhist, Jaina, Parsi, Adivasi, Dalit, others? Why not mainstreaming of films from these traditions? Shouldn’t cinema, considering its massive reach, celebrate this diversity, rather than regurgitate countless times the same old format (with gravity defying antics), just to please the people in power? There is a thin line here between fiction, mythology and Hindutva cultural hegemony and politics and some of these brilliant, organic and thinking actors who people respected, have chosen to become part of it all.

Reasons may be more than artistic.