Taipei: As the Chinese government tightened its grip over its ethnic Uyghur population, it sentenced one man to death and three others to life in prison last year for textbooks drawn in part from historical resistance movements that had once been sanctioned by the ruling Communist Party.

An AP review of images and stories presented as problematic in a state media documentary, and interviews with people involved in editing the textbooks, found they were rooted in previously accepted narratives two drawings are based on a 1940s movement praised by Mao Zedong, who founded the communist state in 1949. Now, as the party’s imperatives have changed, it has partially reinterpreted them with devastating consequences for individuals, while also depriving students of ready access to a part of their heritage.

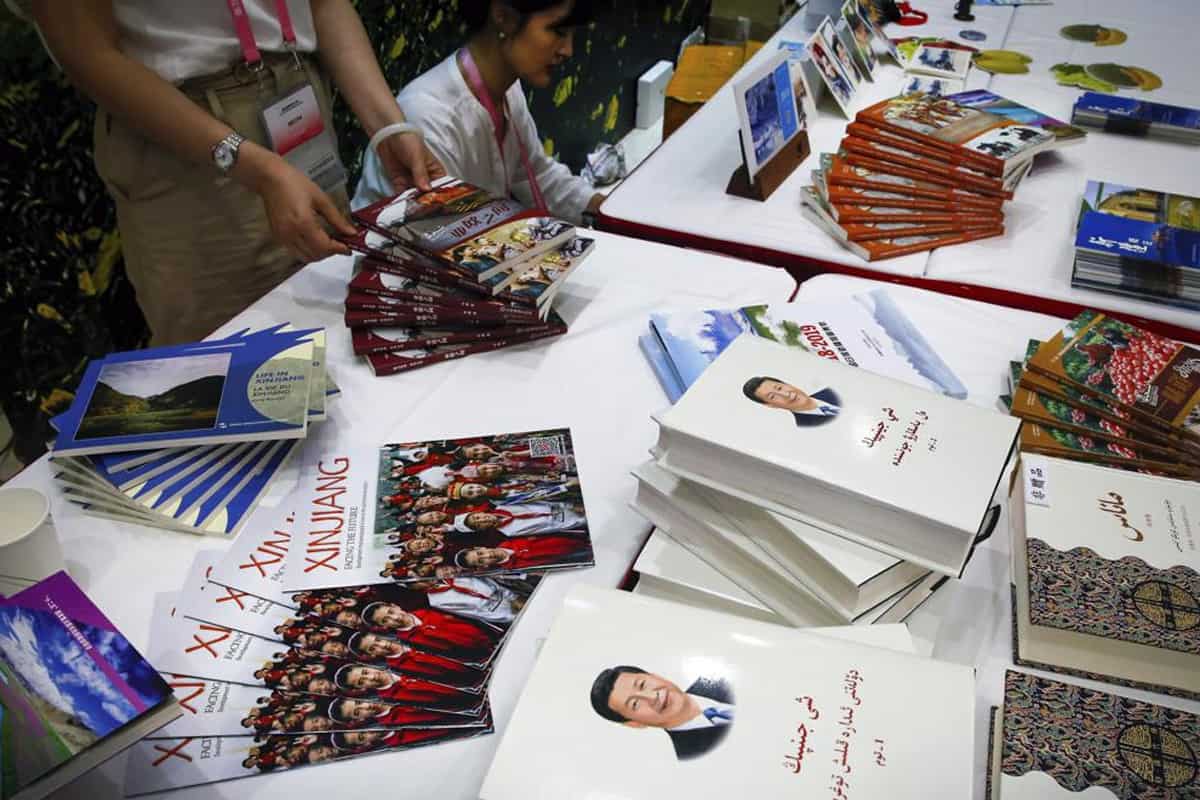

It is a less publicised chapter in a wide-ranging crackdown on Uyghurs and other largely Muslim groups, which has prompted the U.S. and others to stage a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Olympics that open Friday. Foreign experts, governments and media have documented the detention of an estimated 1 million or more people, the demolition of mosques and forced sterilization and abortion. The Chinese government denies human rights violations and says it has taken steps to eliminate separatism and extremism in its western Xinjiang region.

The attack on textbooks and the officials responsible for them shows how far the Communist Party is going to control and reshape the Uyghur community. It comes as President Xi Jinping, in the name of ethnic unity, pushes a more assimilationist policy on Tibetans, Mongolians and other ethnic groups that scales back bilingual education. Scholars and activists fear the disappearance of Uyghur cultural history, handed down in stories of heroes and villains across generations.

There’s much more intense policing of Uyghur historic narratives now, said David Brophy, a historian of Uyghur nationalism at the University of Sydney. The goalposts have shifted, and rather than this being seen as a site of negotiation and tension, now it’s treated as separatist propaganda.

Sattar Sawut, an Uyghur official who headed the Xinjiang Education Department, was sentenced to death, a court announced last April, saying he led a separatist group to create textbooks filled with ethnic hatred, violence and religious extremism that caused people to carry out violent acts in ethnic clashes in 2009. He may not be executed, as such death sentences are often commuted to life in prison after two years with good behaviour.

Details about the textbooks were then presented in a documentary by CGTN, the overseas arm of state broadcaster CCTV, on what it called hidden threats in Xinjiang in a 10-minute segment. It included what amounted to on-camera confessions by Sawut and another former education official, Alimjan Memtimin, who got a life sentence.

The Xinjiang government and CGTN did not respond to written questions about the material.

Drawings from the textbooks are presented as evidence Sawut led others to incite hatred between Uyghurs and China’s majority Han population.

In one, a man points a pistol at another. The image is flashed over an on-camera statement by Memtimin, who says they wanted to incite ethnic hatred and such thoughts.

But both men in the drawing are Uyghurs. One, named Gheni Batur, holds up a gun to a traitor who had been sent to assassinate him. Batur was seen as a people’s hero in a 1940s uprising against China’s then-ruling Nationalist Party over its repression and discrimination against ethnic groups, said Nabijan Tursun, a Uyghur American historian and a senior editor at Radio Free Asia.

The Communists toppled the Nationalists and took power in 1949. Mao invited then-Uyghur leader Ehmetjan Qasimi to the first meeting of a national advisory body and said, Your years of struggle are a part of our entire Chinese nation’s democratic revolution movement. However, Qasimi died in a plane crash en route to the meeting.

Despite Mao’s approval, this period of history has always been debated by Chinese academics, Brophy said, and the attitude has shifted more and more toward hostility.

Another element in the story came to the fore after a series of knifings and bombings in 2013-14 by Uyghur extremists, who were angered by harsh treatment by the authorities.

The Uyghur movement had briefly carved out a nominally independent state, the second East Turkestan Republic, in northern Xinjiang in 1944. It had the backing of the Soviet Union, which had real control.

A recently leaked 2017 document, one of a trove given to an unofficial Uyghur Tribunal in Britain last September, shows that a Communist Party working group dealing with Xinjiang criticised elements of the uprising.

The Three District Revolution is a part of our people’s democratic revolution, but there were serious mistakes made in the early stages, the notice said.

Blaming interference by the Soviet Union, it said that ethnic separatists infiltrated the revolutionary ranks and stole the right to lead, established a splitting regime, … and committed the grave mistake of ethnic division.

The document still said that Qasimi should be respected for his role in history.

The CGTN documentary, though, singles out a photo of Qasimi wearing a medal that was the symbol of the second East Turkestan Republic. It shouldn’t appear in this textbook at all, Shehide Yusup, an art editor at Xinjiang Education Publishing House, said in the documentary.

Another textbook illustration, drawn from the same period, shows what appears to be Nationalist solider pointing a knife at a Uyghur rebel sprawled on the ground.

Both stories come from novels by Uyghur writers published by government publishing houses. One of the writers, Zordun Sabir, is a member of the state-backed Chinese Writer’s Association. The textbooks themselves were published only after high-level approval, said K nd z, a former editor at the Xinjiang University newspaper who uses only one name.