The Sirens of September, Zeenath Khan’s accomplished debut, is a subtle and evocative coming-of-age novel set against the charged backdrop of Hyderabad’s annexation in 1948 under Operation Polo. Told through the diary-like voice of Farishteh, a bright fifteen-year-old pupil at St. George’s Grammar School. Farishteh’s grandfather, her Dadajaan, nurtures her curiosity and quiet courage.

The novel is divided into three parts that trace the fraught years around 1947–48 and culminate in the accession. It offers readers both an intimate personal record and a broader view of a city at a historic turning point. Khan’s prose is direct, favouring vivid scenes and decision-making over unnecessary description. This makes the book feel immediate and engaging while allowing its philosophical moments to resonate deeply. Lines such as “the female gaze is always more dangerous than the male gaze,” and the epilogue’s reflection that “for the living to compete with the dead was impossible,” linger long after the last page.

The book does more than retell events; through letters, interior monologues, and multiple narrations, including that of General Edroos and other authority figures, it explores how class, privilege, and loyalty influenced decision-making during Operation Polo and its aftermath. Khan uncovers how some families’ allegiance to the Nizam and their economic well-being mollified the most brutal of the violence, even as countless others suffered. Dense with local colour, the city streets and monuments of Hyderabad, its cuisine and social observances, the novel also raises an ethical question about survival, memories, and complicity in the figure of Saleem. Sometimes the novel has the directness of Anne Frank’s diary, yet it is firmly anchored within South Asian history and politics. Readers also glimpse the diplomacy and cover-up over those at the very centre of the political disturbance

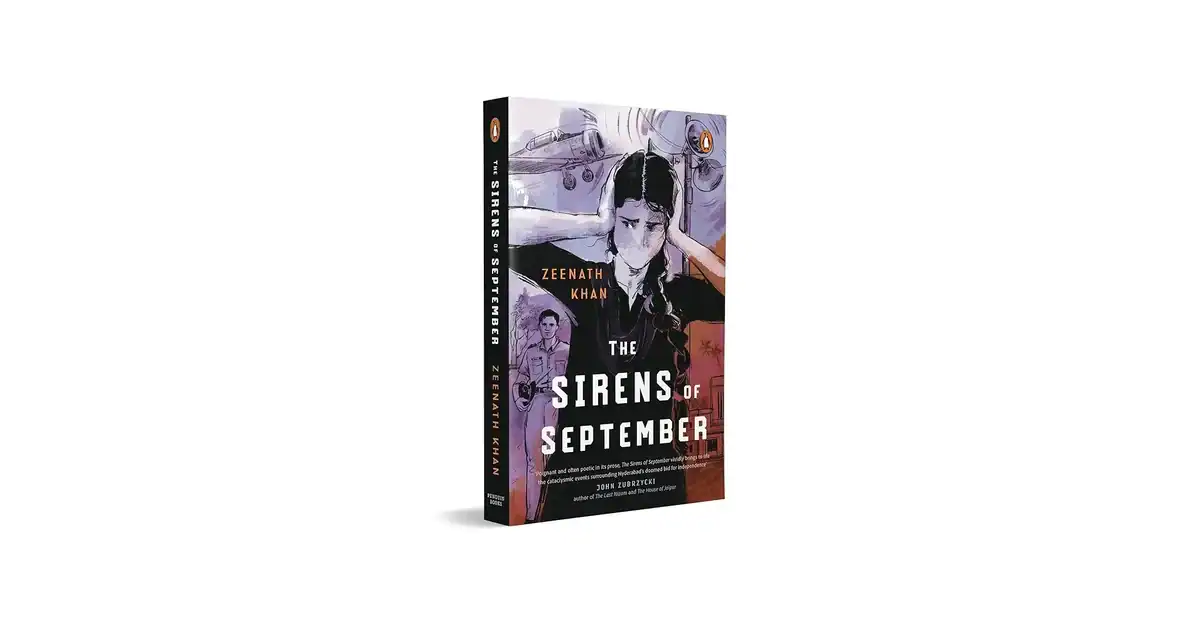

Released in September 2025 by Penguin India, The Sirens of September is both historically informative and emotionally accurate, a powerful addition to modern-day historical fiction of the Deccan. It will resonate with readers of literary coming-of-age stories and those interested in humane fiction relating to the partition-era disturbances. For the high-flyers in Hyderabadi society, access to the Nizam or money may have insulated them from the most severe evils; for others, those safeguards were a pipe dream. The employment of letters and contemplative monologues provides texture and a platform for the readers to sense the hope, fear, and moral burden carried by each character. The writing is lean but powerful, based on not just historical facts but also on dialogue, mood (curfews, protests, the cityscape in transition), and the mundane existence: what people wear, where they seek refuge, and how they arrive at hard decisions. Moments of philosophical reflection exist, reminding us that beneath politics and history are more profound issues of memory, mourning, and reconciliation. History needs to be understood from multiple perspectives, most of all through stories, artwork, and literature. They also reclaim misunderstood voices of the people whose pain and endurance make up the unwritten tapestry of history, offering a more nuanced and humane understanding of what was lost and how people lived through one of the most defining ruptures in Hyderabad’s history.

By Ziniya Al Baha PhD from Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad.