Jeddah: Sudan is one of the mineral rich countries in Africa with abundant water resources that has attracted some Indians who worked in Gulf countries. Some well settled and professional Indians opted to work in the Nile delta for lucrative salaries.

More than a lakh people have now fled Sudan to neighbouring countries in search of safety, the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) said on Tuesday. UNHCR estimates that the number of refugees and returnees may rise to over 8 lakh.

The clashes erupted in the middle of April amid an apparent power struggle between the two main factions of the military regime. The Sudanese armed forces are broadly loyal to Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the country’s de facto ruler, while the paramilitaries of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a collection of militia, follow the former warlord Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti.

Many Indians who are fleeing the country feel sad about the violence in Sudan. Afsar Faheem, Haris Muneer, Mohammed Zia and R. Srinvasa Rao prominent NRIs of Telangana in Sudan – they loved by working in Sudan – all left Sudan recently under Operation Kaveri.

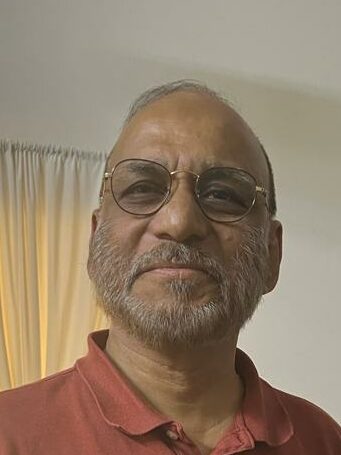

Meet Afsar Faheem, A prominent face of Hyderabadi in Sudan and a former resident of Saudi Arabia, Afsar was one active community member in port city of Jeddah and considered one of the high-end Hyderabadi who was working in a senior position of a leading dairy company before moving to Sudan in 2002.

Like several other Indian expert elites, Afsar Faheem opted to work in Sudan for career and financial reasons.

“Long gone are the heady days when Sudan emerged as one of Africa’s top oil producers and later one of finest gold ore mine country”, said Afsar Faheem.

Speaking with this correspondent prior to returning to Dallas in the USA where he settled, the long time Hyderabadi NRI said that ongoing conflict could spiral into a more deadly crisis than Syria, Yemen and Libya.

“I love Hyderabad that gave me an identity, however, after the demise of my mother there is none left in the city, hence permanently settled in USA”, he added.

When asked he said that he didn’t expect that Sudan will be back to normal in near future.

He added that the country could have emerged one of the richest in Africa with the vast resources of gold ore mines and open up foreign investments.

Afsar Faheem said that he was personally aware of few Hyderabadis who left their attractive salaried jobs in the Gulf region and moved to Sudan for more lucrative salaries.

Not only Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries and Canada, Malaysia, China, India also considerably invested in emerging Sudan.

A prominent politician from Andhra Pradesh bagged the construction contract of a largest thermal power plant in Sudan.

In the late 1990s, amid a devastating civil war, President Omar Al-Bashir’s military-Islamist regime announced that energy would help birth a new economy. It had already paved the way for this reality, ethnically cleansing the areas where oil would be extracted. The regime struck partnerships with Chinese, Indian and Malaysian national oil companies.

Petrodollars poured in. The regime in power between 1989 and 2019 oversaw a boom. This enabled it to weather internal political crises, increase the budgets of its security agencies and to spend lavishly on infrastructure. Billions of dollars were channelled to the construction and expansion of several hydro-electric dams on the Nile and its tributaries.

These investments intended to enable the irrigation of hundreds of thousands of hectares. Food crops and animal fodder were to be grown for Middle Eastern importers. Electricity consumption in urban centres was transformed; production in Sudan was boosted by thousands of megawatts. India’s BHEL also played a constructive role in power generation.

If any single country can be said to geographically dominate the Nile Basin, it is Sudan. The largest country in Africa, it makes up roughly 63 percent of the Basin’s land area, and 75 percent of the country lies within the Basin itself. The Nile runs through the entire country from south to north providing about 77 percent of Sudan’s fresh water. It is also in Sudan where the White Nile and the Blue Nile converge to form the main Nile, giving it a central place in the country’s history and culture.

The regime spent more than US$10 billion on its dam programme. That’s a phenomenal sum and testament to its belief that the dams would become the centrepiece of Sudan’s modernised political economy.

South Sudan

Then, in 2011, South Sudan seceded – along with three-quarters of Sudan’s oil reserves. This exposed the illusions on which these dreams of hydro-agricultural transformation rested. The regime lost half of its fiscal revenues, and about two-thirds of its international payment capacity.

The economy shrank by 10%. Sudan was also plagued by power cuts as the dams proved very costly and produced much less than promised. Lavish fuel subsidies were maintained but as evidence shows, these disproportionately benefited select constituencies in Khartoum and failed to protect the poor.

This economic crisis fuelled a popular uprising which led to the overthrow of Al-Bashir. After the 2018-2019 revolution, the international community oversaw a power-sharing arrangement. This brought together the Sudan Armed Forces, Rapid Support Forces and a civilian cabinet. Reforms were tabled to reduce spending on fuel imports and address the desperate economic situation.