Hyderabad: It is looked down upon by members of Debari community when a girl is unmarried after the age of 16. However, Pooja, 17 years old, has gone against the odds to support her family of four.

She travelled 1350 km south of her village, Debari (Rajasthan), to Hyderabad in Telangana so she could earn money to fund her ailing father’s medical bills.

For someone who had never travelled beyond their village, Pooja underwent a two-night and three-day long train journey to reach Hyderabad for her livelihood. She, along with her uncle’s family of five, travelled to Chittaurgarh from Debari, after which they took a Hyderabad-bound train two-and-a-half months ago in February. They will make the same journey back to Debari once the Deccan monsoon season begins.

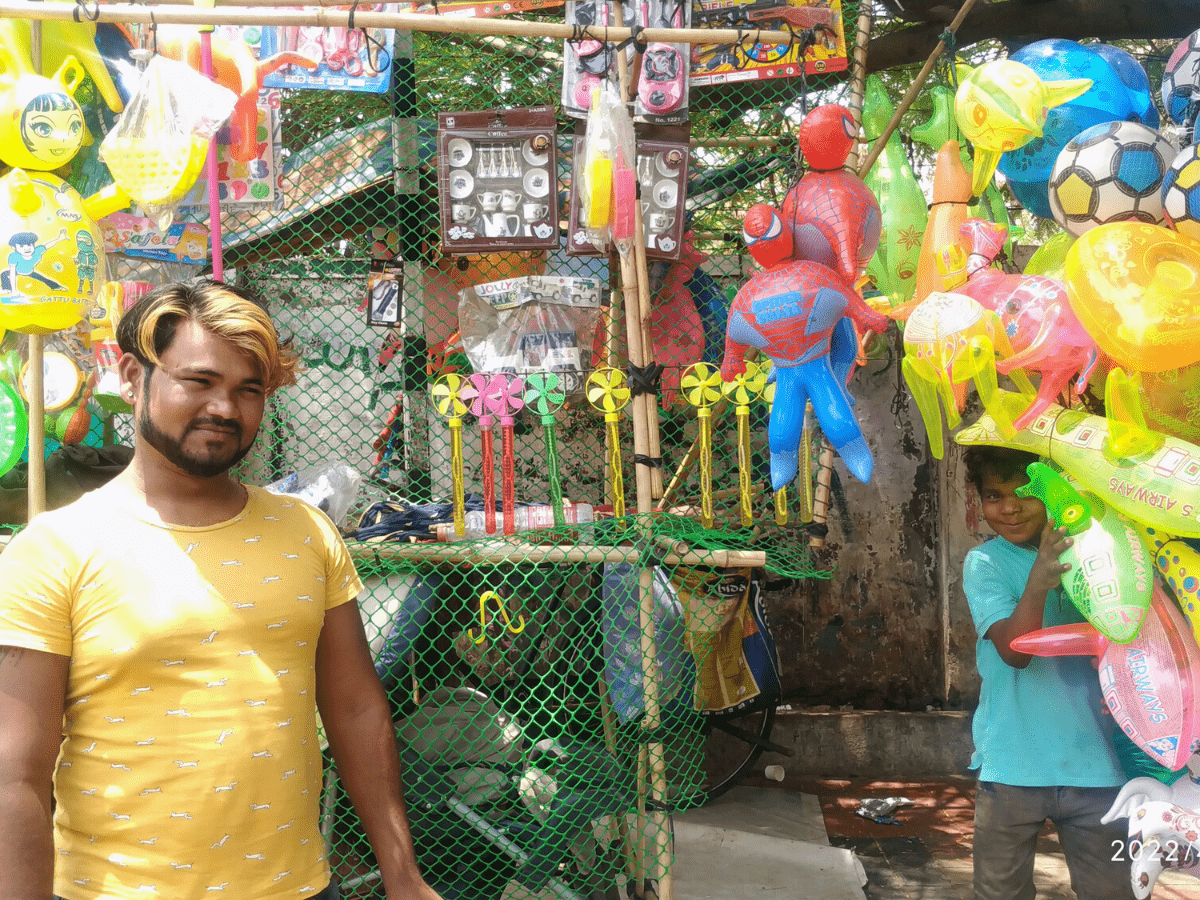

And till they go back, Pooja and her extended family members, a total of 60 odd people, call a 2.5/80-metre stretch of footpath outside the Mehdipatnam garrison their home. They make a living out of selling toys at traffic junctions. She sends the money she makes back to her parents in the village, so it could cover her father’s medical expenses.

The ubiquitous toy sellers across traffic signals we see everyday, are essentially migrant workers who travel to the Deccan to make money every year due to lack of opportunities back home. It’s a routine that cities across India witness, which tells us of the stark realities from rural India.

“We can go beg for money or rely completely on charity, but we don’t want to live like that. We will make an honest living, and go back when the rains come,” said Nirmala Vagariya, a 28-year-old mother of four, who lives with her family on the same footpath at Mehdipatnam.

Traditionally, these families relied on making brooms out of date palms (known as khajoori locally) in foothills of the Aravalli range. However, due to various adverse circumstances, they abandoned their craft and turned to seasonal migration relying on odd jobs for a living.

For 30-year-old Dinesh Lal, who is Nirmala’s husband and Pooja’s uncle, this is the third trip he has made in the last two years. “When the country was locked down due to COVID-19, we had to take a loan of rupees 60,000 from a local landlord to sustain ourselves. The interest on it keeps mounting. So far in this trip, we have managed to save Rs 14,000 collectively.” he said.

Once the younger generation saves enough to sustain themselves for a few months, they go back to their village to take care of the elders of their families whom they leave behind.

A typical workday for the migrant toy vendors begins at 4 pm and ends 12 hours later, at 4 am the following morning. They then sleep on the footpath in their makeshift shelters, wake up around 8 am in the morning and continue till it’s time for work again. In the meanwhile, they cook, wash their clothes, eat, and sleep all on the small piece of scorching hot cement footpath. The women use Mehdipatnam bus stop’s paid public toilet services.

“As a family of five, we require a minimum of Rs 300 to survive per day. The paid-toilet facility charges us Rs 30 for one shower, and Rs 10 if we have to use the washroom. Apart from that, we require Rs 250 to buy flour and other rations to cook. Since there is no electricity available to us, we pay Rs 10 to nearby shops to charge our phones,” said Nirmala, while explaining her daily routine in Hyderabad.

They also rely on local people’s day-to-day acts of kindness to keep safe from the wrath of officials. “The owner of Shah Ghouse provides us with water, which suffices for our day-to-day needs. People also stop by and donate clothes to them every now and then.” Dinesh and Nirmala collectively said.

“The police have asked us to vacate this place as soon as Ramzan is over. We have not thought about what we will do next. We will see when Ramzan is over.” they added.

Meanwhile, one of the soldiers responsible for security at the Mehdipatnam garrison said, “These people usually keep to themselves. They are not around through the night and are only seen during the day. We do not see any harm in letting them stay around the garrison as long as they do not create trouble for anybody.”

Parents of another four young boys, who did not want to be named, said, “We miss our home. We spot so many wild animals and be surrounded by greenery. Now we have headaches from all the honking and traffic. We can’t even go for manual daily-wage work. Who would look after our children then? What to do? We can’t fill our children’s stomachs with all the views.”

Every year, Telangana witnesses an inflow and outflow of seasonal migrants who come to the state in search of a better livelihood. The main reason for it is the availability of better work opportunities and appreciation of their skills in the state. However, when inter-state seasonal migrant workers such as Dinesh and Nirmala prefer to find odd jobs independently, they bypass the ‘system’. This prevents them from availing the security and benefits assured by the Inter-state migrant workmen Act, 1979.