Since time immemorial, people across cultures have been looking down upon women for their assumed enfeebled existence, but curiously the invincible might of the nation-state is primarily imagined in terms of feminine sensibilities. Nation and women share several traits, such as purity, chastity, and piety that must be protected.

This flimsy admiration aside, women continue to be the object of the stifling affliction of subjugation, marginalization and gender equality. The pitiable condition of Muslim women in India, their boundless deprivation and their servitude to patriarchal misrepresentation of religion look self-evident. Not many know that through determination and self-belief, daughters of destitution knocked over many unsurpassable hurdles and attained unprecedented success.

Undeterred by searing double jeopardy, some determined Muslim women weaved a gripping and admirable narrative of self-discovery and phenomenal individual growth that strengthened collective consciousness, empowerment and national aspirations in the six decades. They have had many firsts to their credit. The fairly long list includes the names of Fathima Bibi ( the first female supreme court judge who took over in 1989); Suraya Tyabji; (the incredible artist who designed our national flag in 1947); Begum Akhtar (the first female singer who judiciously wrapped up Vivadi Sur in Ghazal singing and earned the title of Ghazal Queen), Sania Mirza (the first Indian woman to win the ATS tennis title) Rokeya Sakhwat Hussain, ( jotted down the first female utopian novel, Sultana’s Dream”, 1905 in which gender roles were reversed.) Ismat Chughtai (the first fiction writer who explored various dimensions of the forbidden female sexuality in her short story Lihaf), Rasheed Jahan (edited an anthology of short stories, Angare that presented a poignant and heart wrenching account of exasperating struggles that women have to confront in the patriarchal society) and Qurratul Ain Haider (who judiciously used stream of consciousness to explore and reflect upon the gender injustices). Some Muslim women such as Razia Sultana, Chand Bibi and Begums of Bhopal, especially Sultan Jahan, committed themselves to the male-driven and exhausting path of leading the country, and they mapped new terrains of courage, bravery and governance. However, their contribution to collective life is not adequately documented.

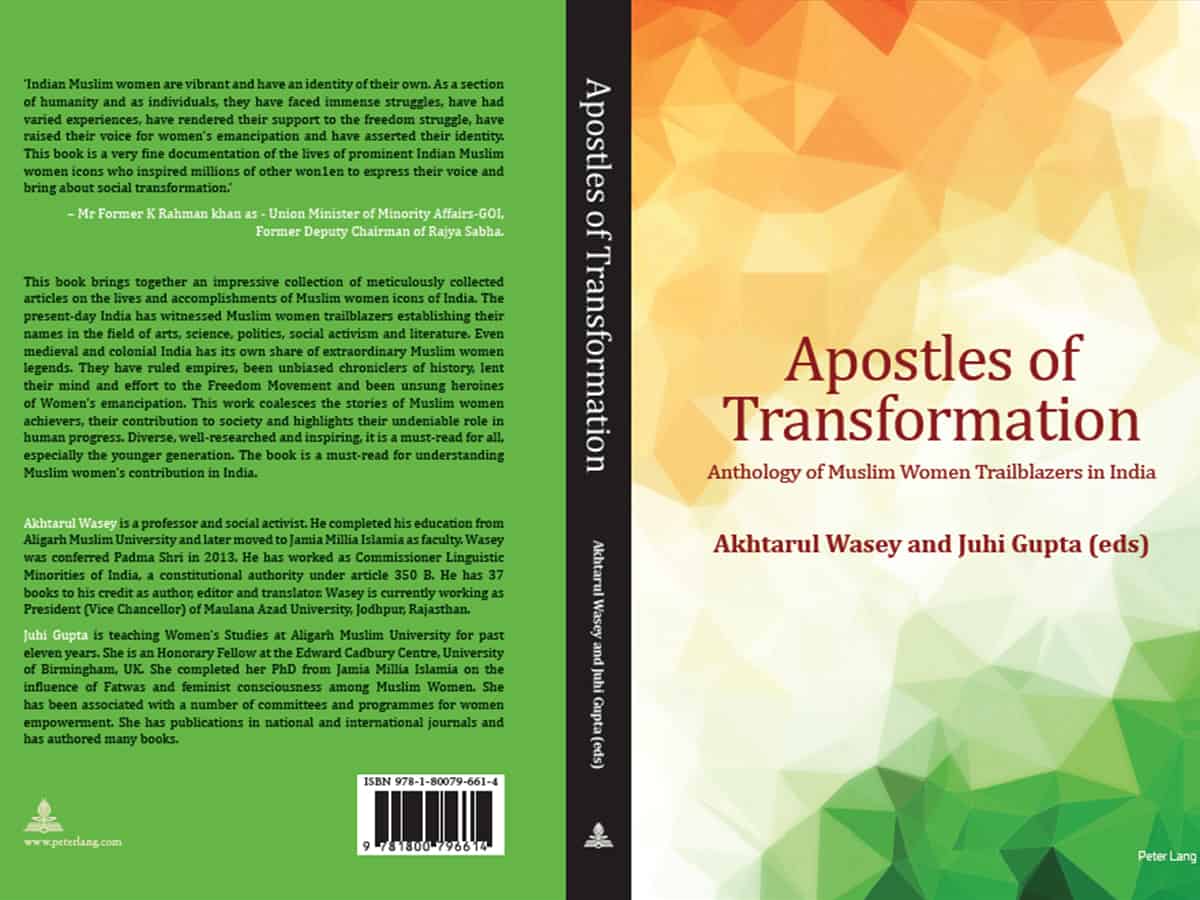

These vital pieces of information largely lay in oblivion and have been aptly articulated and cogently documented in an astutely edited anthology of Muslim women trailblazers, Apostle of Transformation, published recently (Peter Lang, 2022). The anthology, edited by a well-known Islamic scholar Akhtarul Wasey and a promising academician Juhi Gupta, carries an assortment of 23 articles that engages the constitutive acts of turning mundane life into moments of epiphany by Muslim women. Their pulsating and coming-of-age experiences need to be told candidly.

Akhtarul Wasey and Juhi Gupta took pains to upend the widespread but erroneous perception that hardly considers Muslim women beyond being silent and passive onlookers. The book produces a gripping and layered narrative of those women who are to be reckoned as role models, but why their awe-inspiring efforts have not fetched the requisite response? As a central premise of the study, this question hardly took off, and the editors dish out a laudatory and partially plausible answer instead. For Wasey and Juhi, Muslim women, by and large, sump up a story of hope and resilience, and they assert, “In reality, Indian Muslim women, in the past and the present, have exerted their freedom, identity and agency. One way or the other, they have found ways to create, contribute, act and participate in various fields and ascended to prominence. Be it art, science, nation-building or politics, there have been hordes and hordes of Indian Muslim women pioneering, participating and contributing to development in the specific field.”

The creative dexterity, sweep of learning and speculative intelligence of Muslim women resonate with almost every genre of literature and non-fiction, and Urdu is not the only beneficiary. Azarmi Dukht Safavi, Rakshanda Jaleel, Rana Safavi, Annie Zaidi, Sami Rafeeq, Nazia Erum, Rana Ayub, Ghazala Wahab, Huma Khalil, Zehra Naqvi, Reema Ahmad, Nasra Sharma, Sadiqa Nawab Saher and the like make it for Persian English and Hindi with remarkable success. Their stories bear witness to what the editors asserted in the preface.

Several prominent authors and academicians, including Syeda Hameed, Rasheed Kidwai, Madhu Rajput, Bharthi Harishankar, Shahida Murtaza, Sabiha Hussain Ayesha Muneera, Azra Musavi, Shiangini Tandon, excavate details and they set forth a discourse whose emotional arc looks irresistible.

The book zeroes in on many prominent women by employing the case study method. Syeda Hameed, in her ear-to-ground and empathetic story of an accomplished author Saliha Abid Hussain whose fifty books, including her profoundly consequential autobiography, Silsila-e- Roz-o- Shabh (sequence of Days and nights), hardly got the recognition she deserved. It rightfully peeved Syeda Hameed, who candidly enumerated her oeuvre by observing that she was a chronicler of her times with natural talent for storytelling and, above all, a woman who believed, practised, and propagated her religion in its most liberal and humanitarian spirit.

Not many knew that Qudsiya Sikandar, Shah Jhan and Sultan Jahan were more than fortuitous rulers of Bhopal. Rasheed Kidwai employed laudatory idiom for adeptly documenting how their rule saw justice, gender sensitivity, peace and reforms even as faith and traditions remained intact. Surayya Tayyabji’s incredible artistic dexterity and pivotal role in designing our tricolour continue to elude public attention, and Shahida Murtaza’s academic rigour-filled succinct article, Surayya Tayyabji, the Resolute woman, supplements it.

The dreadful and calamitous partition is dotted with poignant tales of sufferance, and heart wrenching stories of the abducted women remained inarticulated. It was the turn of a celebrated author and activist, Begum Anees, who put together permeating and nuanced memories of the event and its earth-shattering aftermaths from the standpoint of women subjected to unprecedented affliction. Azra Musavi made her autobiography, Azadi Ki Chaon Mein (In Freedom’s Shade), the object of a single pristine look. Azra’s lucid close reading of the text draws forth an informed debate on how the two states faltered in fulfilling the aspiration of people.

Ayesha Muneera astutely spells out the contours of Rokeya Sakhawat Hussain’s creative world, and she argues that Sultana’s Dream is a feminist, political, and ecological utopia. She sides with Nilanjana Bhattacharya by terming it an anti-colonial text. For her, the novel works against India’s colonialization and internal colonization of women within Indian society. Rokeya’s trail-blazing text subtly conjures a dystopian world where gender roles are reversed, but the environs remain dreadful.

Naima Khatoon produced an evocative piece on Begum Akhtar, one of the most accomplished singers of Ghazal, Dadra and Thumri that India ever produced. She blended music and poetry with remarkable ease.

In her article, Sabiha Hussain ropes in feminist and cultural studies tools to map the creative terrains of Ismat Chughtai and Qurratul ain Haider.

Juhi Gupta turns her attention to the family of Sheikh Abdullah, the pioneer of Muslim women’s education, and she perceptively analyses the contribution of Begum Abdullah, well-known educationist Mumtaz Jahan, famous author Rasheed Jahan and prominent actor Begum Khurshid Mirza (Renuka Devi).

Shah Alam insightfully unravels the vanguards of change, and his laconic account, Vignettes of Muslim women Politicians in India reads well.

Faiza Abbasi, Mayuri Chaturvedi, Chand Bi, Tauseef Fatima, Bharti Hari Shankar, Rekha Pandey, Abida Quansar, Madhu Rajput, Bilal Wani, Naseem Shah, Shirin Sherwani, Shivandgini Tandon, Ruchika Verma, Anam Wasey and Huma Yaqub are the other contributors who made the anthology an intriguing read.