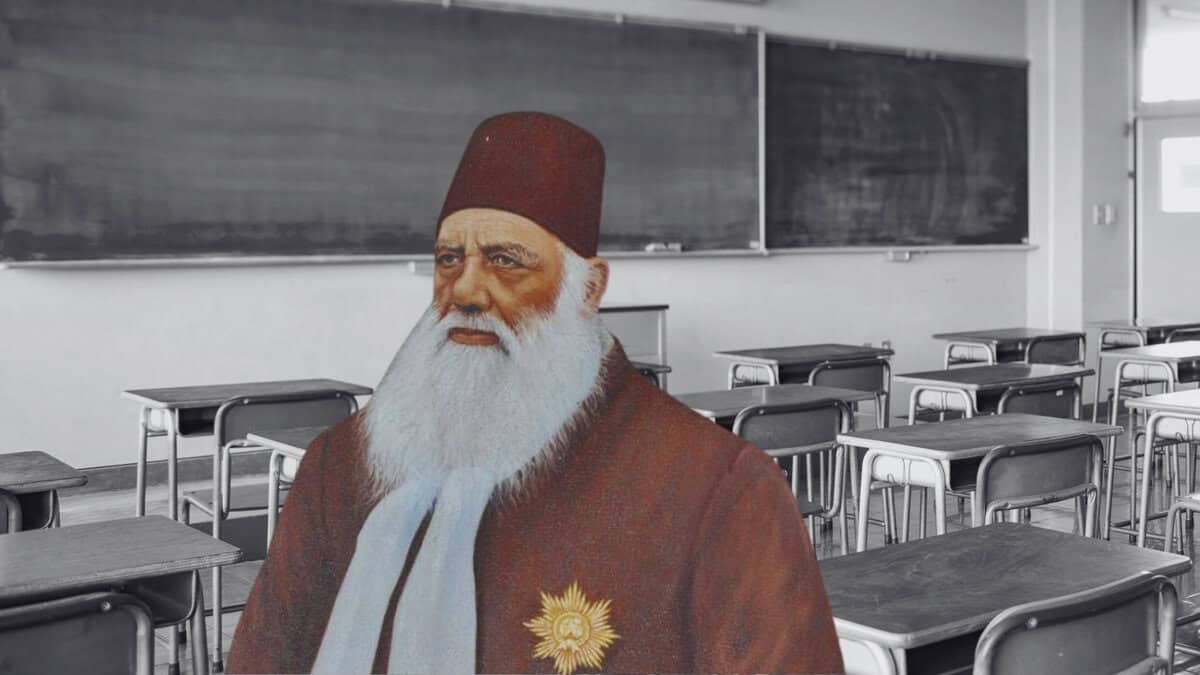

Syed Ahmad was born in a well-known family of notables who had served with distinction in the Mughal Administration. His upbringing was one of careful grooming, characteristic of those who belonged to his social class. He absorbed his spirituality from his father, who was a deeply religious man. He was tutored by his maternal grandfather, who had distinguished himself in the service of both the British East India Company and the Mughal Emperor. He grew up imbibing the noble values of his forebears and, from these values, he crafted his moral compass, which unfailingly and unswervingly guided him through life’s journey.

The calamitous events of 1857-58 coincided with the mid-point of Sir Syed’s life. With the failure of the great rebellion, any hope of releasing India from the British grip had been shattered to smithereens. The freedom dream of the rebels had soured into a sordid nightmare. The severity of British reprisals had pulverised the nation’s aspirations and morale, establishing beyond doubt that British domination was cruel and complete. The colonial masters were there to stay and rule. The old order had irretrievably drowned in a sea of crimson, and a new Sun rose in the Eastern horizon, one that would not set on the British Empire for almost another century.

Through this pall of gloom, Syed Ahmad saw rays of hope. He began to pick up the pieces of the crushed confidence of his community and tried to bind them together with the glue of education. From that darkest hour emerged a new dawn. The Aligarh Movement was born. His vision, built upon the bedrock of pragmatism and the courage of convictions, led him to overcome significant barriers and hurdles and establish a new reality that would, in the ripeness of time, flourish as the University of his imagination: the Oxford-of-the-East!

While the MAO College was founded in 1875 (first as Madrasatul Uloom), it was not until 1920 that Aligarh Muslim University saw the light of day, twenty-two years after Sir Syed passed away. Syed Ahmad’s vision was not just a College that would become a University, but an Educational Movement whose impact would be deep and wide across the length and breadth of the Indian landscape. With this objective in mind, he established the Muhammadan Educational Conference in 1886. Sir Syed’s purpose was to bring various regional initiatives already being taken under a unified umbrella. The Conference did much to keep the hope of a Muslim University alive, and every annual session, 1898 onwards, demanded the establishment of Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh itself being the venue for five of the first eleven sessions of the Conference. The Conference became an effective medium through which Muslim opinion was conveyed to Muslims across the nation. A vestige of this organisation still exists in Aligarh, though barely, and its current state hardly merits comment. Will the Muslim Educational Conference be revived? Or substituted by another organisation, is an open question. Emulating the practice of this historic, but now defunct, Conference, an assembly of Muslim thought leaders should be convened annually to ponder over the educational needs of the community and to draw up an implementable action plan. Will those who laud Sir Syed lead as he did, or will they be content to bury this powerful idea in the very place where it was born?

Sir Syed’s success story cannot be repeated without two key characteristics that underpinned his achievement: vision and courage. Both seem to be immensely scarce. Sir Syed’s vision was moulded from his ability to think out of the mould, to break with conventional thinking and seek out a new paradigm, to reconceive the future. We cannot reimagine the future while our imagination is so narrowly constrained within impermeable boundaries. Leaders must not only be guided by vision, they must also have the courage to say it as they see it. Leadership is about influencing and shaping opinion, about setting the direction and pace of change. That is what made Sir Syed a remarkable leader, whose impact has reverberated long after him.

At a time when the community is in dire need of direction, AMU’s role in providing thought leadership is both obvious and lacking. This unique academic setting ought to produce valuable thinking and research about the critical challenges facing the Muslims of India and the nation, examine these challenges from different perspectives, locate them within their proper context, and illuminate possible ways to alleviate and remedy the many ailments that afflict us. In the current context, it is incumbent upon AMU to play a role much larger than that of a conventional university. That will not happen unless the University’s leadership sets up structures and processes that facilitate the desired outcomes.

On this occasion of his birth anniversary, let the spirit of Sir Syed move us from mere exhortations to concrete action that would mark a step change in our situation. His spirit beckons us to rise above ourselves and punch above our weight, much as he did. This requires that we imbibe his courage, his determination, his sincerity, and his perseverance in the pursuit of purpose. Can we rise to the challenge and answer his call? I would like to hope that we can!