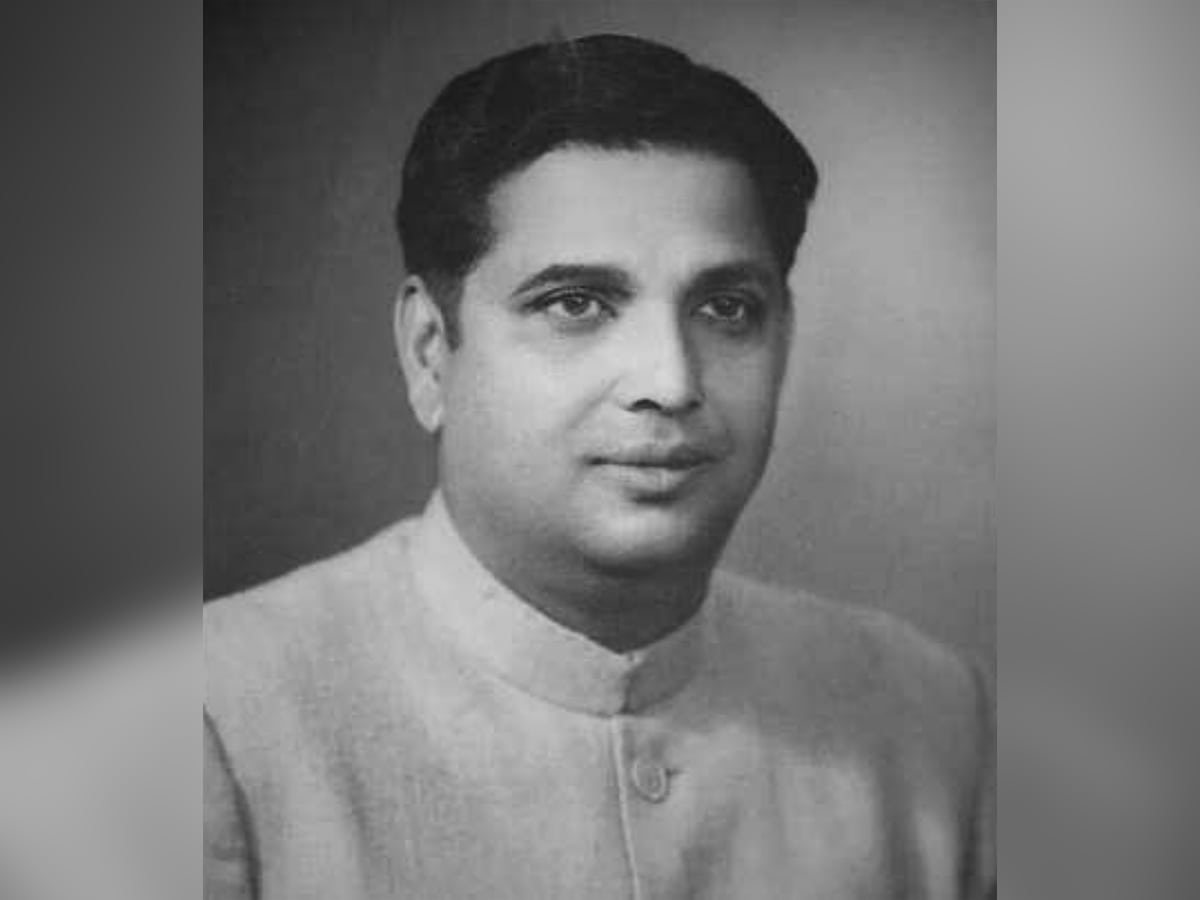

Nelson Mandela and B P Mandal were born in the same year in 1918. Mandela fought against apartheid, a system of racial segregation in South Africa, while B P Mandela fought against casteism, a system of discrimination in India. Mandela became first Black President of South Africa in 1994. B P Mandal became the first lower caste Chief Minister of Bihar in 1968. Mandela established a multiracial democracy in South Africa; Mandal through Mandal Commission opened the new avenues for the upliftment of the marginalized and gave voice the voiceless. B. P. Mandal is known for chairing the Mandal Commission, which recommended 27% reservation for the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in government jobs and educational institutions. His report sparked a nationwide debate on caste, class, and social justice in India and changed the political and social landscape of the country.

Mandal was born on August 25, 1918 in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, to a Yadav family from Madhepura, Bihar, which is considered as one of its OBCs in India. His father Ras Bihari Mandal was a philanthropist, founding member of Indian National Congress and a leader of Indian Independence movement. Ras Bihari Mandal wrote a book titled Bharat Mata Ka Sandesh during Bang-Bhang movement.

Mandal received his education from Patna University. He was influenced by the socialist ideas of Ram Manohar Lohia and Jayaprakash Narayan, who advocated for the empowerment of the oppressed and exploited sections of society.

Mandal began his political career in 1941, when he became a member of the Bhagalpur district council at the age of 23. He joined the Indian National Congress and contested the first general elections in 1952 from the Madhepura assembly seat, defeating Bhupendra Narayan Mandal of the Socialist Party. He raised his voice against the caste-based discrimination and atrocities faced by the backward classes in Bihar, especially during the Pama incident in 1954, when local Rajput landlords attacked a Kurmi village and the police sided with them.

Parting ways with Lohia

He also demanded land reforms and redistribution of land to the landless peasants. Mandal left the Congress in 1967 and joined the Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP), led by Lohia. He became the president of the SSP and won the Lok Sabha election from Madhepura constituency. He also served as the health minister in Bihar when Mahamaya Prasad Sinha was the chief minister. However, he soon parted ways with Lohia over ideological differences and formed his own party called Shoshit Dal in March 1968. He became the seventh chief minister of Bihar on February 1, 1968, with the support of other parties, but resigned after only 30 days due to political instability.

Mandal returned to the Lok Sabha in 1977 as a member of the Janata Party, which was formed by the merger of various opposition parties against Indira Gandhi’s Emergency rule. He was appointed as the chairman of the Second Backward Classes Commission by Prime Minister Morarji Desai in December 1978. The commission was mandated to identify the socially and educationally backward classes of India and suggest measures for their advancement. The commission used 11 social, economic, and educational indicators to determine backwardness and conducted extensive surveys and studies across the country. The commission submitted its report in December 1980, which revealed that OBCs constituted 52% of India’s population and faced severe deprivation and discrimination in various spheres of life. The commission recommended that OBCs be granted 27% reservation in central government jobs and public sector undertakings, in addition to the existing 22.5% reservation for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), thus making the total reservation quota 49.5%. The commission also suggested that similar reservation be implemented in educational institutions, legislatures, local bodies, and other fields.

Muslims feature among OBCs

The commission also recognized that some OBCs among Muslims faced caste-based discrimination and included them in its list of backward classes. The Mandal Commission report was a landmark document that sparked a nationwide debate on caste, class, and social justice in India. However, it was largely ignored by successive governments until V. P. Singh announced its implementation on August 7, 1990, as the prime minister of a coalition government supported by both left-wing and right-wing parties. His decision triggered massive protests and agitation by upper-caste students and anti-reservation groups, who saw it as a threat to their privileges. Many students committed self-immolation or violence to oppose the reservation policy.

The reaction of upper castes to Mandal Commission was largely negative and hostile. Many upper-caste groups opposed the reservation policy and saw it as a threat to their privileges. They staged massive protests and agitation across the country, especially in urban areas and educational institutions. Some of them even resorted to self-immolation or violence to express their dissent. The Supreme Court intervened and stayed the implementation of the report until it heard a petition filed by Indra Sawhney and others challenging its constitutional validity. Indra Sawhney was a lawyer and social activist who filed a public interest litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court of India challenging the reservation policy for the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) based on the Mandal Commission report. She was the main petitioner among several others who opposed the implementation of the report by the central government.

She argued that the reservation policy violated the constitutional guarantee of equality of opportunity, that caste was not a reliable indicator of backwardness, and that the efficiency of public institutions was at risk. Her case, known as Indra Sawhney v. Union of India, was heard by a nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court, which delivered its landmark verdict in 1992. The court upheld the validity of the reservation for OBCs but also imposed certain conditions and limitations, such as excluding the “creamy layer” or affluent sections among OBCs from the benefit of reservation, setting a ceiling of 50% on total reservation, and ruling out reservation in promotions.

Rise of Hindutva

Indra Sawhney’s role in the Mandal Commission case was significant as she brought to the fore the complex and contentious issues of caste, class, and social justice in India. The upper-caste backlash also gave rise to the Hindutva or Kamandal politics, which sought to counter the Mandal mobilisation by appealing to the Hindu identity and polarising the society along communal lines. The upper-caste reaction to Mandal Commission thus reflected their resentment and resistance to the social justice movement that aimed to empower the backward classes of India.

In November 1992, a nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court delivered its verdict, upholding the Mandal Commission report with some modifications. The court ruled that reservation based on caste was permissible under Article 16(4) of the Constitution, which empowers the state to make provisions for reservation for any backward class of citizens. The court directed the government to periodically review and revise the list of backward classes and the criteria for reservation. The court also suggested that reservation should not be the only means of achieving social justice and that other measures such as scholarships, hostels, coaching, etc. should be provided to the backward classes.

The ‘creamy layer’ among OBCs is a term that refers to the relatively affluent and well-educated members of the Other Backward Classes, who are excluded from the benefits of the 27% reservation quota for OBCs in government jobs and educational institutions. The concept of the ‘creamy layer’ was introduced by the Sattanathan Commission in 1971 and upheld by the Supreme Court in the Indra Sawhney case in 1992. The criteria for determining the ‘creamy layer’ are based on the income, rank, and status of the parents of the OBC candidates. The current income limit for the ‘creamy layer’ is Rs. 8 lakh per annum, which was last revised in 2017. However, there have been demands to increase the income limit or exclude it altogether, as well as to include other factors such as landholding, education, and occupation in the criteria. The issue of revising the ‘creamy layer’ criteria has been pending for years and has been raised by several MPs in the sessions of Parliament.

New political figures emerge

Mandal implementation gave rise to new political parties and leaders who represented the aspirations and interests of the backward classes, such as Mulayam Singh Yadav, Lalu Prasad Yadav, Nitish Kumar, Mayawati, etc. It also led to the emergence of new social movements and alliances among various subaltern groups, such as Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims, women, etc. It also provoked a backlash from the upper castes and the right-wing forces, who resorted to communal polarization and violence to counter the assertion of the backward classes. The Mandal Commission report thus became a symbol of hope in India’s quest for social justice and democracy. B. P. Mandal died on April 13, 1982, before his report was implemented. He did not live to see the impact of his work on Indian society. He was a man of courage and conviction, who stood for the cause of the oppressed and exploited masses. He was a visionary who foresaw the need for a radical transformation of India’s social structure and polity. He was a reformer who advocated for a more inclusive and egalitarian society. He was a leader who inspired millions of people to fight for their rights and dignity. He was a legend who left behind a legacy that continues to shape India’s destiny.

Dr. Sandeep Yadav is an Associate Professor at University of Delhi