India’s informal sector occupies interstate migrants working in precarious conditions for lower wages, with inadequate legal and social support mechanisms. The vulnerability was exposed during the COVID-19 lockdown when thousands of migrant workers started walking to their homes throughout the entire expanse of the country.

Apart from the economic hardships, they deal with inadequate healthcare, food insecurity, and harsh living conditions and are victims of prejudice and exclusion. The multifaceted everyday story of millions of such faceless working-class Indians rarely gets attention from policymakers, let alone media platforms.

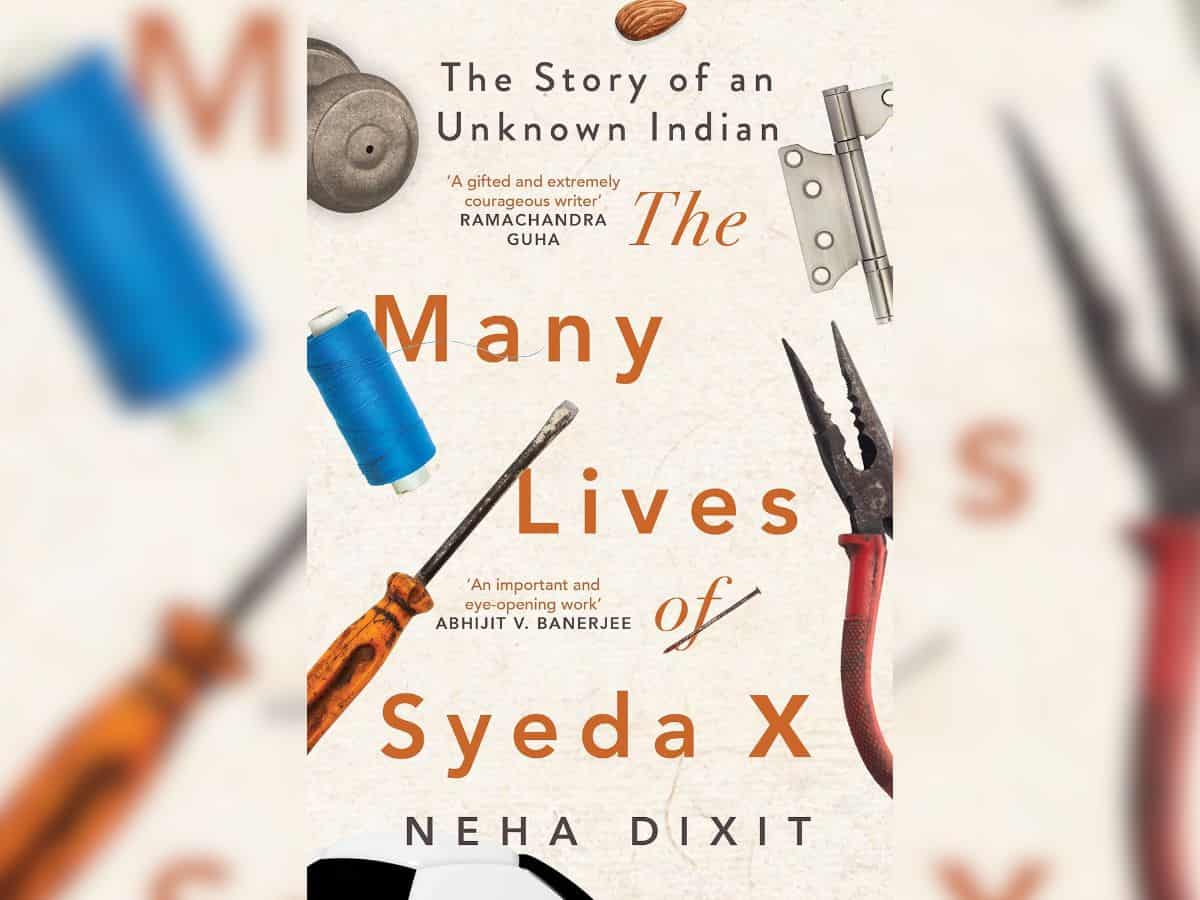

A recently released book, The Many Lives of Syeda X, by award-winning journalist Neha Dixit, is the story of one such faceless working-class Indian woman who left her hometown Banaras for Delhi in the aftermath of riots following the devastation of Babri Masjid. Syeda X, the protagonist in the book, started doing multiple jobs to make ends meet, from shelling almonds to cooking namkeen.

The Centre for Development Policy and Practice (CDPP) hosted a book discussion on Saturday, September 13, 2024, in Hyderabad. The author sheds light on the experiences of women workers who do not identify themselves as traditional labourers.

These women are home-based workers, often employed indirectly by major corporations. Instead of being paid for their time, they are compensated based on the amount of work they produce. For instance, Syeda took on multiple jobs in Delhi, including shelling almonds, for which she earned Rs 50 for cleaning a 23-kilo bag, a task that consumed 12 to 16 hours of her time.

Home-based workers make up a substantial segment of total employment, particularly in Asia, where 66 percent of the world’s 260 million home-based workers are located. Globally, women account for 57 percent of home-based workers, balancing income-generating activities with childcare and household responsibilities. The book paints a compelling picture of Syeda’s life as a home-based worker, a narrative that mirrors the experiences of the “second largest source of informal employment for women in India, after agricultural work.”

In India, there are 41.85 million home-based workers, including 17.19 million women, and 12.48 million engaged in non-agricultural occupations, according to data from the 2017–18 Periodic Labour Force Survey analysed in a 2020 report by Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing.

Who is a home-based worker?

A home-based worker is defined as someone who performs paid work within their home or in nearby premises. There are two types: self-employed workers, who source their own materials and manage their expenses and revenue, and homeworkers or industrial outworkers, who are paid per piece by factories. While homeworkers often receive raw materials, they still bear many production costs, such as workspace, equipment, and utilities.

Home-based workers are involved in various labour-intensive and capital or information-driven activities. Common occupations in India include beedi rolling, garment production, agarbatti making, gem cutting, and food preparation, such as papad, pickle, among others.

These workers face numerous challenges, including unpredictable work orders, rejected goods, delayed payments, and inconsistent supplies of raw materials, particularly for homeworkers. Self-employed workers also face the risk of fluctuating demand and rising costs. The workers face difficulties stemming from the dual role of their homes as workplaces due to limited space, poor conditions, insecure housing, and lack of essential services, resulting in low earnings. Financial necessity often drives individuals to engage in home-based work.

An ethnography of 900 people

Dixit’s book is a product of her ethnography of 900 people, which she conducted for almost a decade. With a chronological structure, the book explores three significant themes. One is the reality that women’s informal, home-based work is crucial for sustaining Delhi’s small and medium-sized industries.

Two is the perception of shared roles and responsibilities in domestic life. Third, the community’s role in offering support and comfort in both situations. The narrative approach is not often explored: it tells the tale of a woman in its entirety rather than through fragmented moments from her daily life.

In many of today’s domestic and global supply chains, a significant portion of production occurs off the factory floor through an unseen workforce—homeworkers. This informal work is marked by vulnerability, as homeworkers lack social and legal protections, economic mobility, and opportunities for collective bargaining—key components of the decent work agenda established by the ILO.

Despite their economic contributions to global production, the roles and impacts of homeworkers are largely overlooked or undervalued by the brands they serve, as well as by consumers and governments. Their isolation often limits access to market information, and many homeworkers remain unaware of their economic significance or their status as legitimate economic agents.

Dixit’s book is an eye-opener for all readers, shedding light on the unseen and untold realities of people who form the backbone of our economy. The words “you do not know Syeda X, but you have seen her” serve as a reality check, highlighting the millions of “Syedas” around us.

About the writers

Ablaz Mohammed Schemnad is a Research Associate at the Centre for Development Policy and Practice (CDPP). He has a master’s in Development Studies from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Hyderabad, with a semester from Sciences Po Lille. His interests lie in migration studies, mobility polices and political economy of caste, class, and religion.

Apoorva Ramachandra is a Research Associate at the Centre for Development Policy and Practice. She has a Master’s degree in Economics from the Jindal School of Government and Public Policy. Her areas of research include development economics, urban development, environment, and gender.