By Lubna Ludheen

Imagine a young girl in rural India dropping out of school because she cannot afford sanitary pads, or a woman in an urban slum enduring infections due to lack of clean toilets during her period. This is the stark reality of period poverty, an issue that extends far beyond just access to menstrual products; it encompasses a severe lack of awareness, adequate wash facilities, and dignity.

As the world observed Menstrual Hygiene Day on May 28, a crucial moment to break the silence and dismantle the deep-rooted stigma surrounding menstruation, it is imperative to look beyond superficial solutions. Organisations like Goonj have championed grassroots innovation in this space.

Following the insightful Menstruation Dialogue 2024, the upcoming Menstruation Dialogue 2025 on May 31 at the India Habitat Centre (IHC), New Delhi, promises to further bridge research, policy, and on-ground solutions, centering community wisdom to foster a future where menstruation is truly seen as a human issue rooted in dignity.

Understanding ‘period’ poverty

The phrase “period poverty” is used to describe the lack of access to safe and affordable menstrual products, coupled with insufficient hygiene education, clean toilet facilities, and proper disposal mechanisms. However, its roots run deeper, intricately linked to systemic issues like poverty, gender inequality, social taboos, and the prejudices of caste, worsened by the disparities between rural and urban areas.

According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), while 76.15% of women in India exclusively use hygienic period products, a notable urban-rural divide persists—89.37% of women in urban areas use hygienic methods compared to 72.32% in rural areas. While the percentage of women using hygienic menstrual products has significantly increased over time from 55% to 84%, the definition of “hygienic methods” includes sanitary napkins, tampons, menstrual cups, and locally prepared napkins. Notably, 64.4% of women aged 15–24 use sanitary napkins, but 49.6% still use cloth, which is often debated as a hygienic option depending on usage.

Globally, menstrual hygiene access varies significantly. The World Bank estimates that 500 million women lack access to menstrual products and adequate facilities for managing their periods hygienically. Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) is comprehensively defined as using clean menstrual materials, having access to safe disposal methods, and being able to change in privacy with soap and water.

This perpetual cycle of deprivation puts individuals at a higher risk of reproductive tract infections and other health complications. It also inflicts immense emotional and psychological trauma and continuous shame, which hinders their overall development and participation in society, leading to issues like school dropouts. Breaking this cycle of deprivation requires a comprehensive understanding of these layered inequities.

Stigma, silence: Cultural context

Beyond the material deprivation, menstrual well-being in India grapples with deeply ingrained cultural stigma. For countless individuals, menstruation remains wrapped in a perception of being “dirty” or “impure” in homes across the country. This belief often translates into social restrictions, barring menstruating individuals from participating in daily activities like entering temples, touching food in kitchens, or even engaging fully in school activities. This pervasive silence—at home, in schools, and across society—fosters an environment for misinformation, deepening shame and anxiety for those experiencing periods. While significant strides have been made in recent years to challenge these taboos, especially with increased awareness campaigns, it is crucial to acknowledge that such restrictive practices and misconceptions, though not universal, continue to be relevant and impact the lives of many, particularly in rural and marginalised communities.

Goonj’s approach: Dignity and development

Goonj is an organisation that has been addressing issues of rural development, poverty, and environmental sustainability for over 26 years. Goonj’s philosophy, deeply rooted in dignity-driven development, ensures that rural communities actively engage in their progress rather than passively receiving aid. A crucial aspect of their approach is a circular economy model, reimagining waste as a valuable resource.

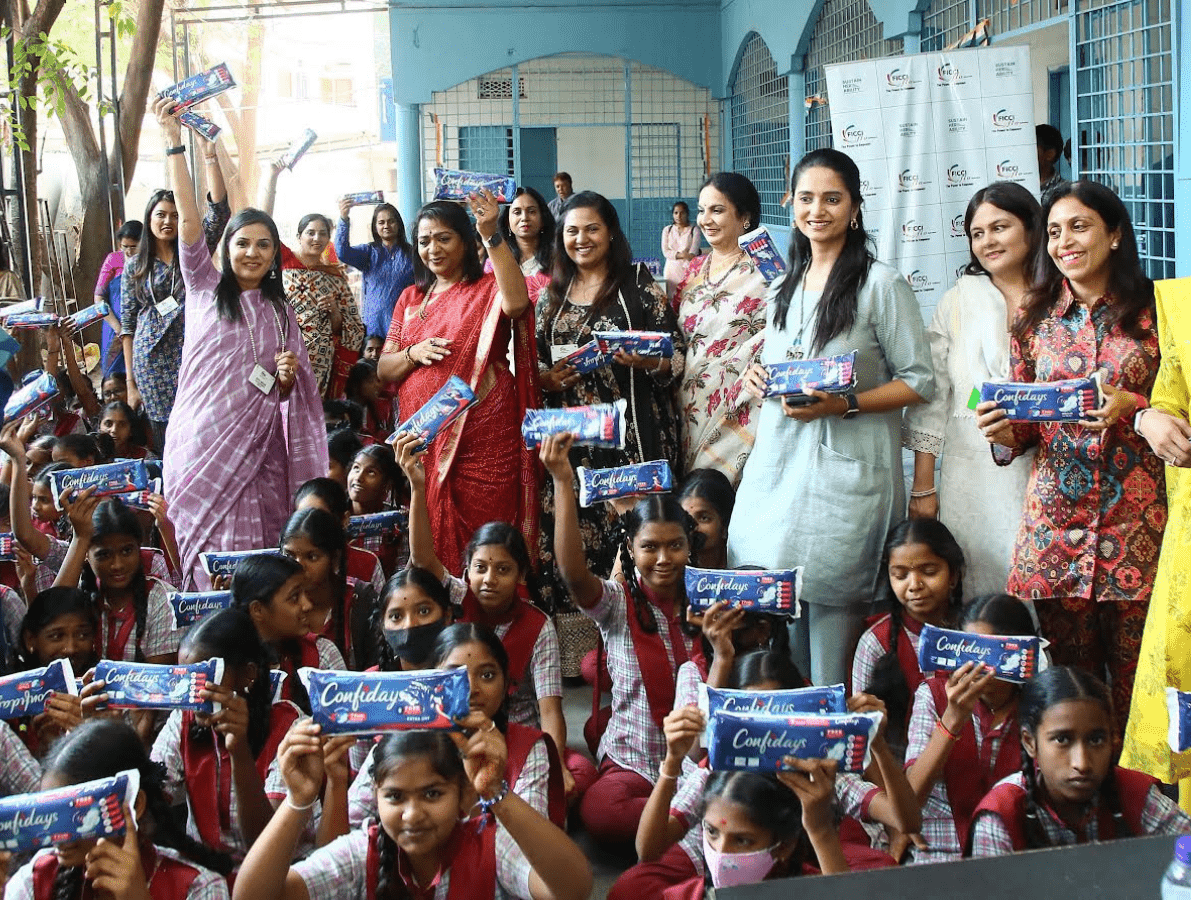

One of Goonj’s flagship initiatives is “Not Just a Piece of Cloth” (NJPC), which tackles three core challenges related to menstrual health: accessibility, affordability, and awareness. Through NJPC, Goonj produces MYPads—reusable sanitary pads made from discarded cloth.

NJPC aims to mainstream menstruation as a human issue, focusing on women’s voice, dignity, and health. Goonj uses surplus cloth to produce cloth sanitary pads and holds pan-India “Break The Silence” dialogues. In 2022–2023, 31,000 kg of cloth were transformed into MYPads. Over 1.3 million MYPads have been distributed through more than 3,300 awareness sessions in rural communities. The introduction of MyPad ATMs, typically a trunk or suitcase filled with cloth MYPad packs, in rural-regions allows easy access to reusable menstrual products at a nominal price, with 38 such ATMs installed in various villages. Since 2014–2022, more than 5 million kg of textile waste has been repurposed by Goonj for various utility items, including clean cloth sanitary pads, while also creating livelihoods for women.

Policy and systemic gaps

Despite recent policy developments on menstruation, significant systemic gaps continue to slow down menstrual well-being. While the 2023 Draft Menstrual Hygiene Policy and the subsequent Menstrual Hygiene Policy for School-Going Girls 2024 for school-going girls aim to provide free sanitary products, implementation faces hurdles like a lack of financial clarity, absence of a per-student budget, and sustained funding mechanisms, raising questions about feasibility.

Menstrual education, though encouraged in curriculum integration, often lacks comprehensive teacher training and student-led sessions, perpetuating misinformation. Furthermore, sanitation infrastructure remains a critical challenge; despite claims of separate school toilets, many are non-functional, unhygienic, or unsafe, particularly in rural and tribal regions. The environmental burden of non-biodegradable commercial sanitary napkins is also immense, with an estimated 100 crore used pads generated monthly in India. These gaps underscore the urgent need for a more robust, funded, and inclusive policy framework.

Call to action

Advancing in menstrual hygiene transcends mere access to products; it is fundamentally a public health, education, and human dignity issue. Addressing this challenge demands an inclusive approach. Solutions must prioritise community-led initiatives, exemplified by organizations like Goonj, which centres grassroots voices and dignity-driven development. Simultaneously, government efforts must scale up consistently, ensuring financial clarity and sustained funding for policies like the Menstrual Hygiene Policy for School-Going Girls. Comprehensive menstrual education must be integrated into school curricula for all genders, fostering open dialogue to dismantle taboos and reduce stigma from a young age.

Conclusion

Menstrual equity is not just a health concern but a fundamental cornerstone of gender justice and an equitable society. A truly just society ensures that no menstruator misses school, loses work opportunities, and suffers in silence due to their natural bodily functions.

The Menstruation Dialogue 2025, organized by Goonj in collaboration with CDPP and NFI, offers a vital space to co-create sustainable, dignity-driven solutions, and build inclusive pathways for menstrual well-being. We invite you to join this collective action, and by working together, we can dismantle stigma, address systemic gaps, and make periods a normal part of life, ensuring dignity for every cycle.

Lubna Ludheen is a Research Associate at CDPP. She has a Master’s degree in Public Policy from Mount Carmel College, Bengaluru. Her research interest areas include women and gender, sexual and reproductive health and rights, and sustainable development.